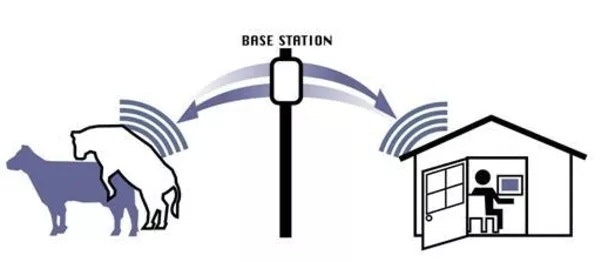

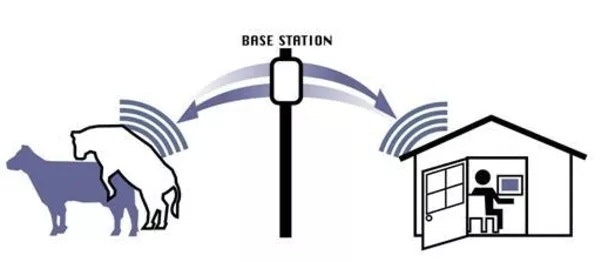

Two critical technological developments of the last three decades have opened a field of possibility in which assemblages of animal and inanimate capacities can be made to perform new labour for humans. First, the miniaturisation of photo, video and radio recorders and transmitters, and second, their energy-efficiency. GPS, GLS and cellular surveillance (or what is more commonly addressed with the benign term telemetry when it concerns nonhumans) are some of the technics that seem eerily suited to interface with animals. An exemplary international project is

ICARUS, which, beginning in July 2018, will continuously monitor tens of thousands of insects, birds, bats and fish from the International Space Station using extremely lightweight radio equipment. The data is distributed via the free

Movebank database. “Once we put together all the information on mobile animals”, ICARUS project head and ornithologist Martin Wikelski reports

in a promotional video, “then we have a completely different, new understanding of life on Earth”. ICARUS merely extends to a planetary scale what is already commonplace locally. Gulls with GPS are

used to discover illegal waste dump sites in Spain, and vultures additionally equipped with GoPro cameras

do the same in Peru.

Wireless ‘Marine Skins’ are being developed for oceanic animals to log environmental data, and stray dogs wearing “smart vests”

patrol neighbourhoods in Bangkok. The vests are equipped with bark-activated cameras, delegating the autonomy for initiating the recording (and thus responsibility for data management) to the dogs. In another example that went viral some months ago, Dutch police recently began

training eagles to hunt another flighted surveillance species, illegal drones. Meanwhile, police drones in California are treated “

like a canine unit”. As an “

Internet of Animals” wants to connect lost pets and simultaneously analyse their emotions and health data

[4], old Aibo robot dogs

receive Buddhist funerals in Japan, and a company in the US uses radio transmitters glued to cows’ bodies to

monitor their estrus cycles and algorithmically analyse details of their mounting activities in order to “[save] time, labor, semen, and money”.