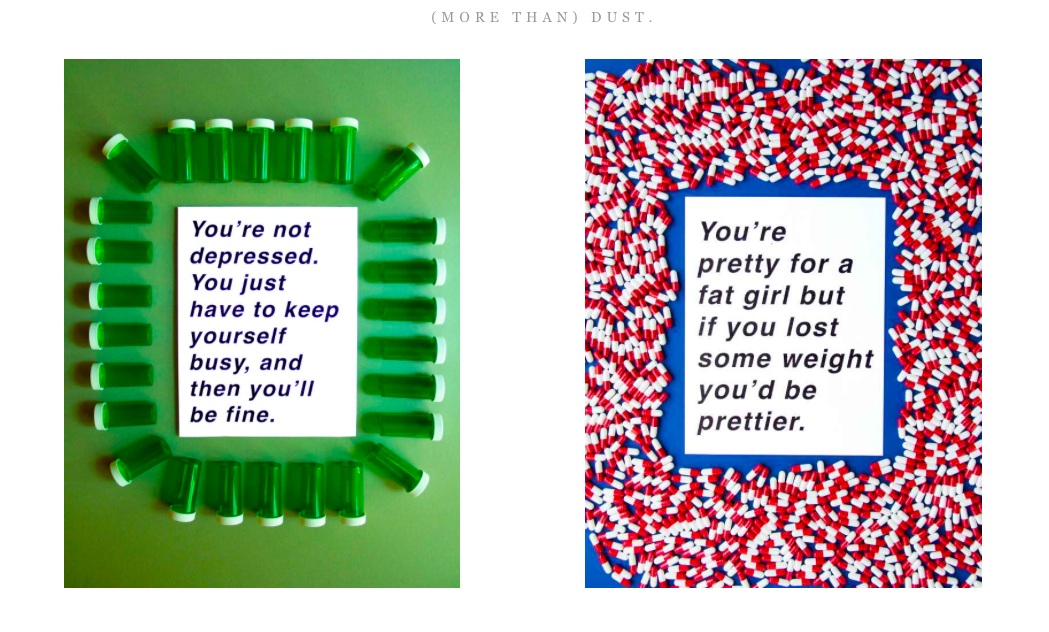

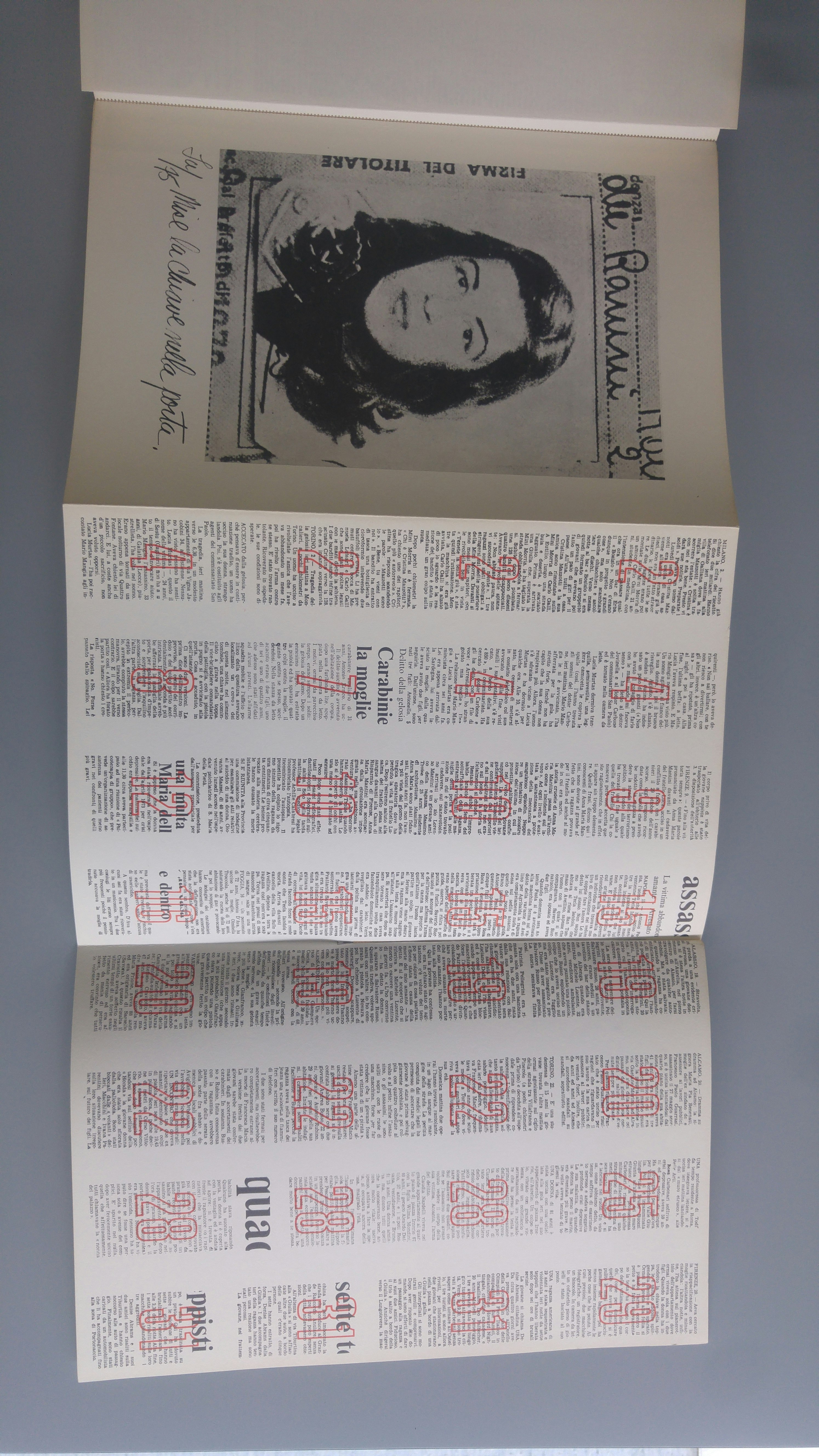

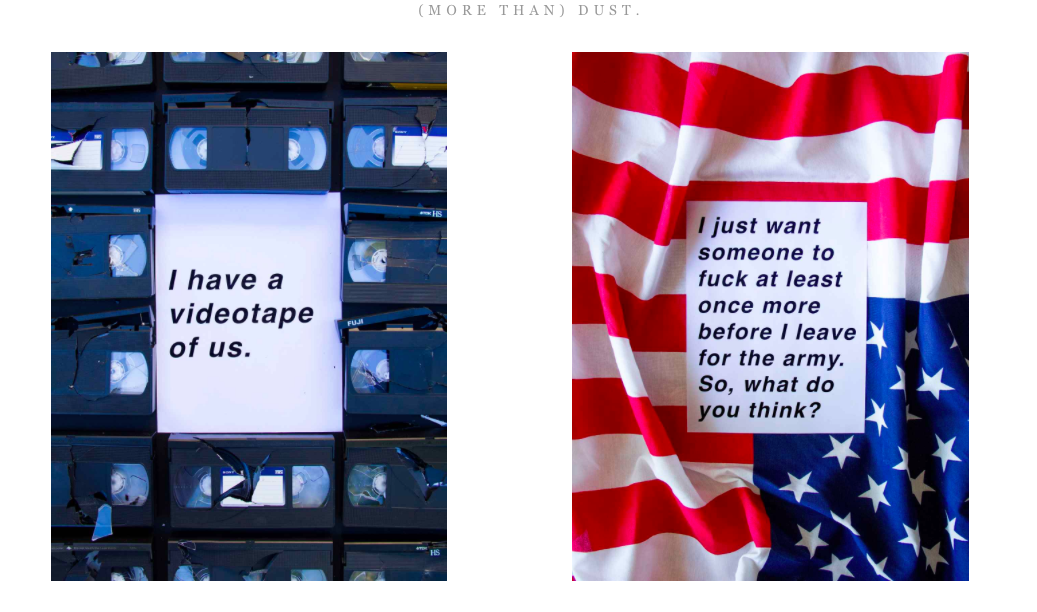

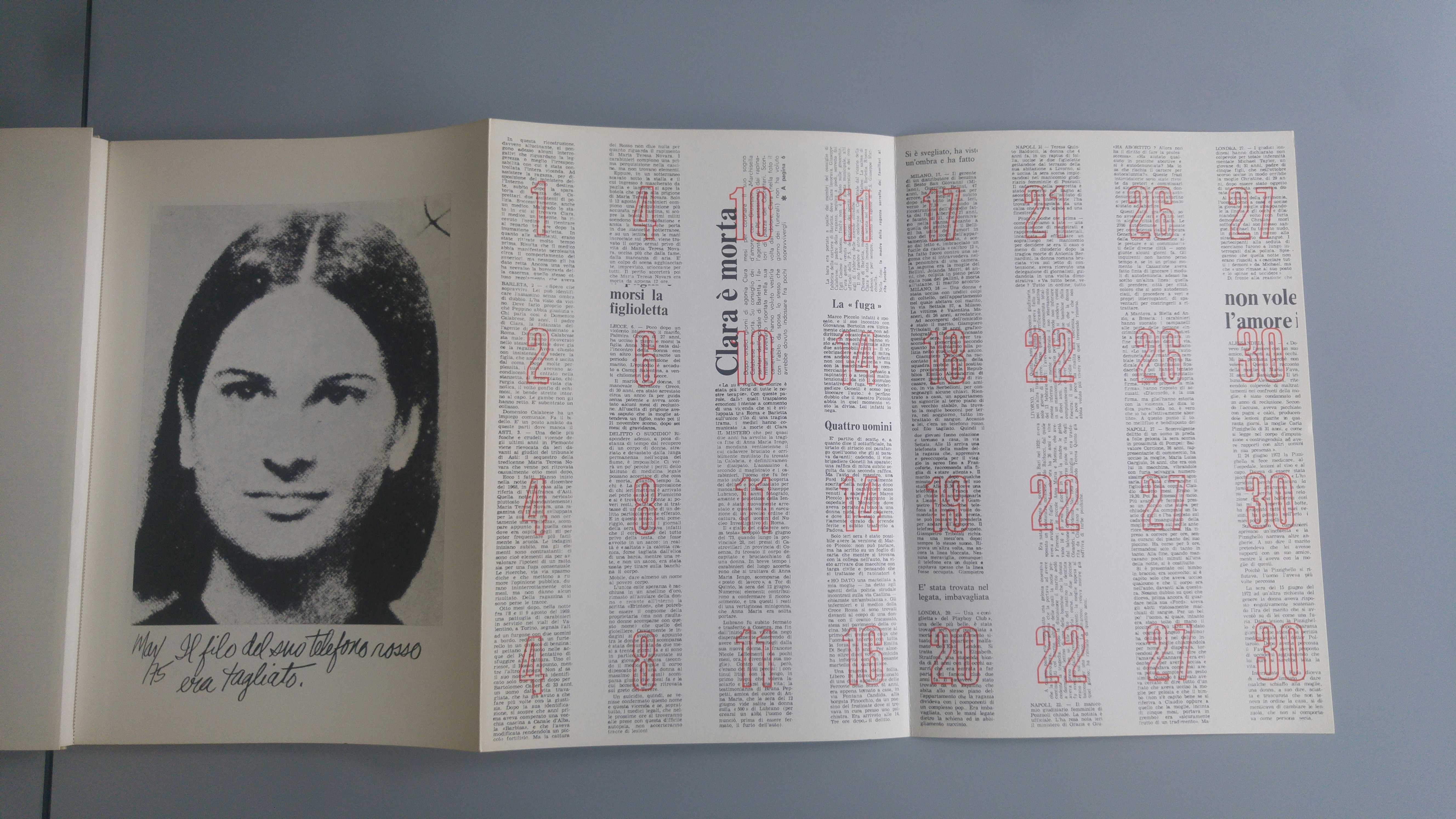

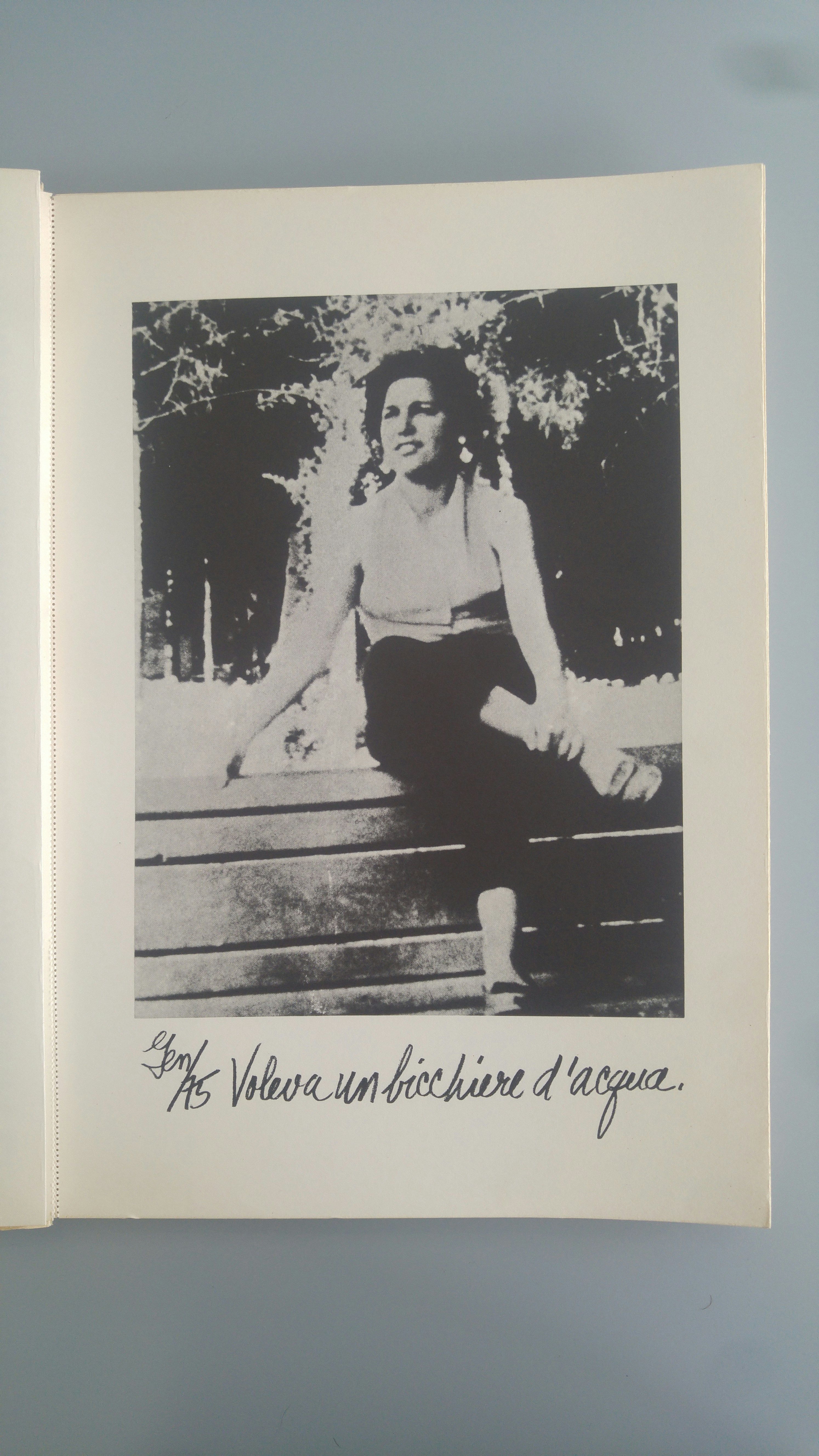

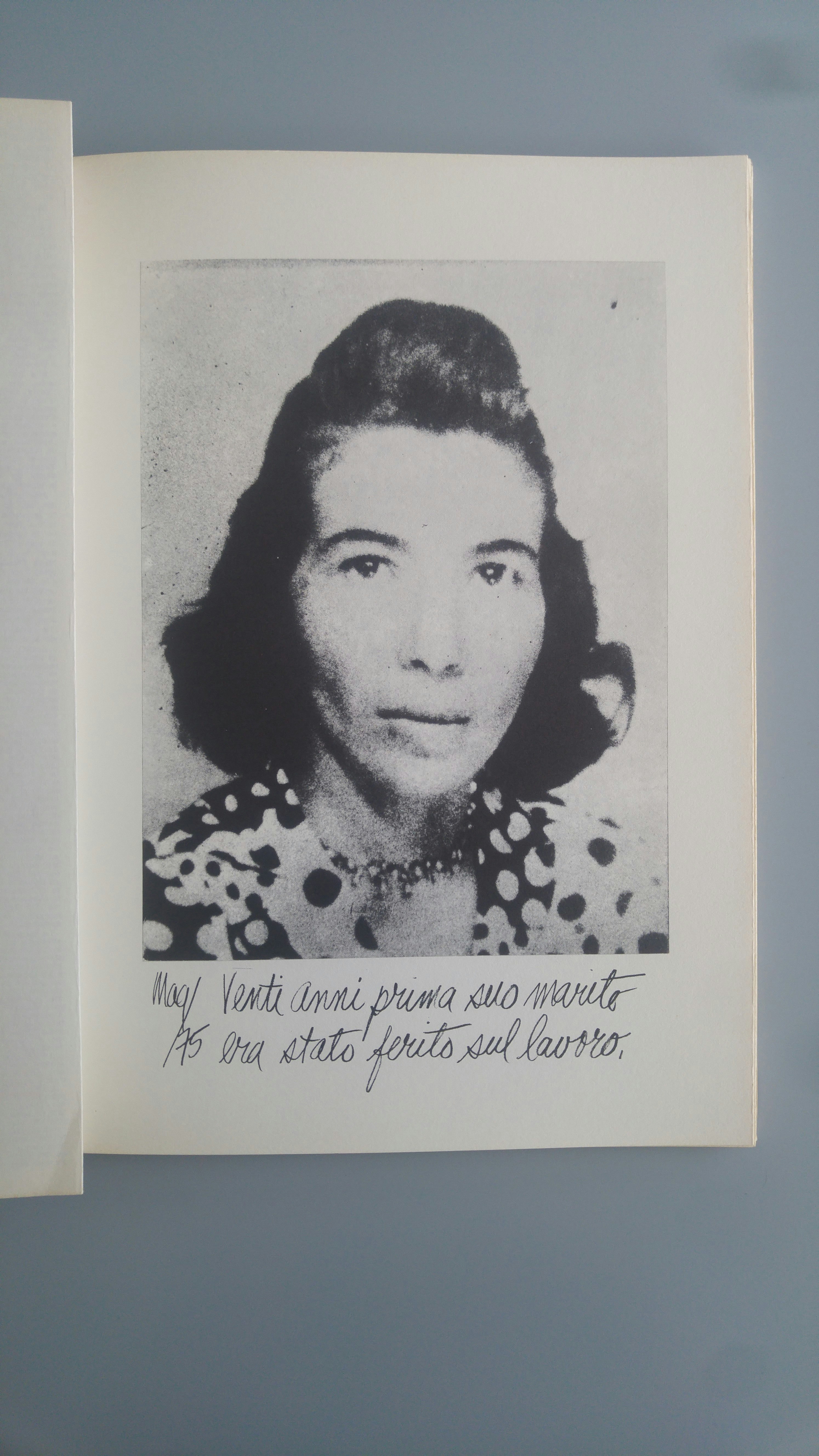

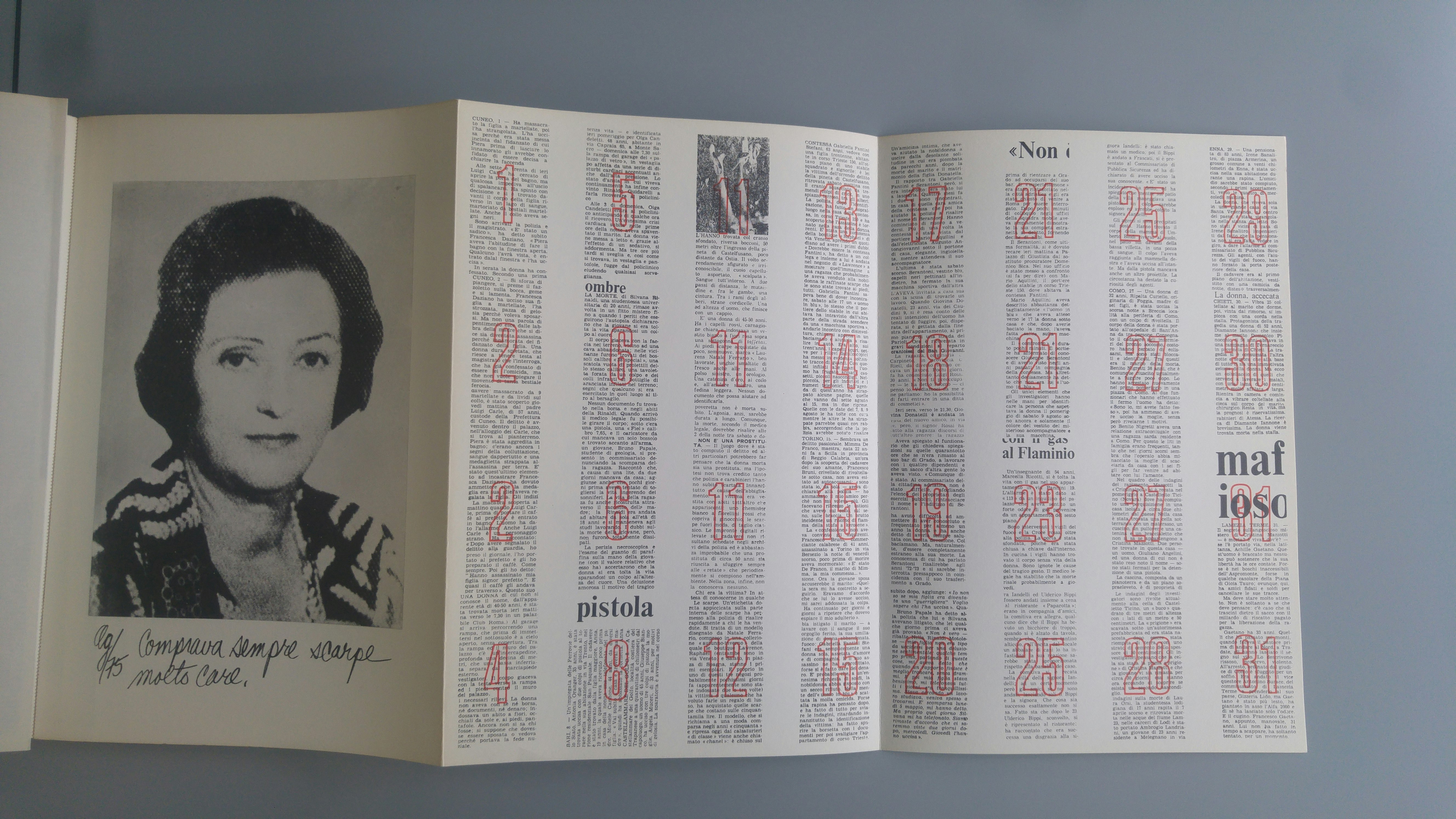

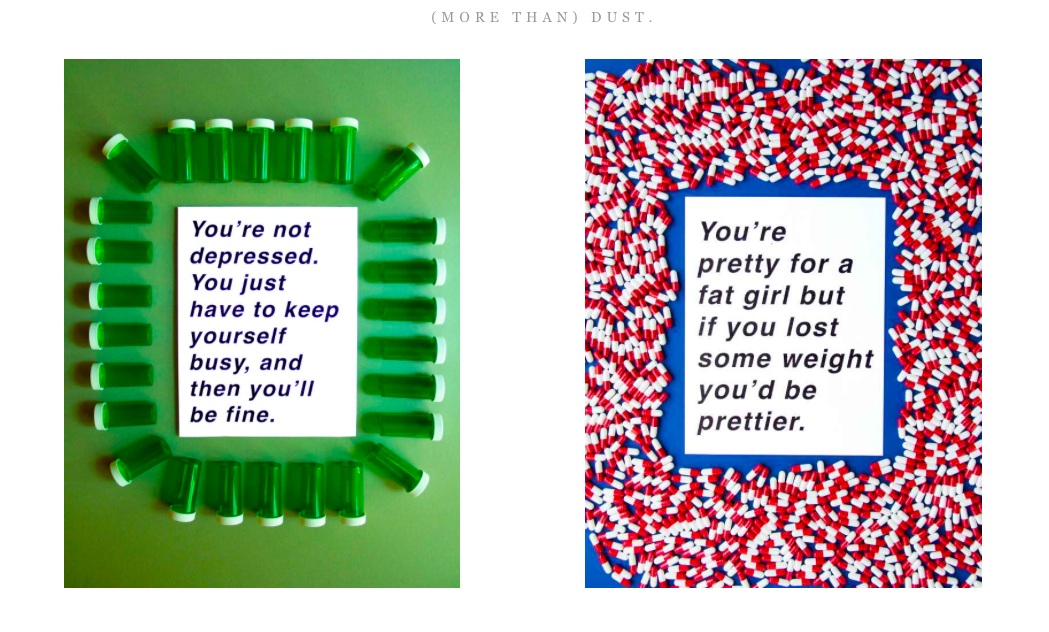

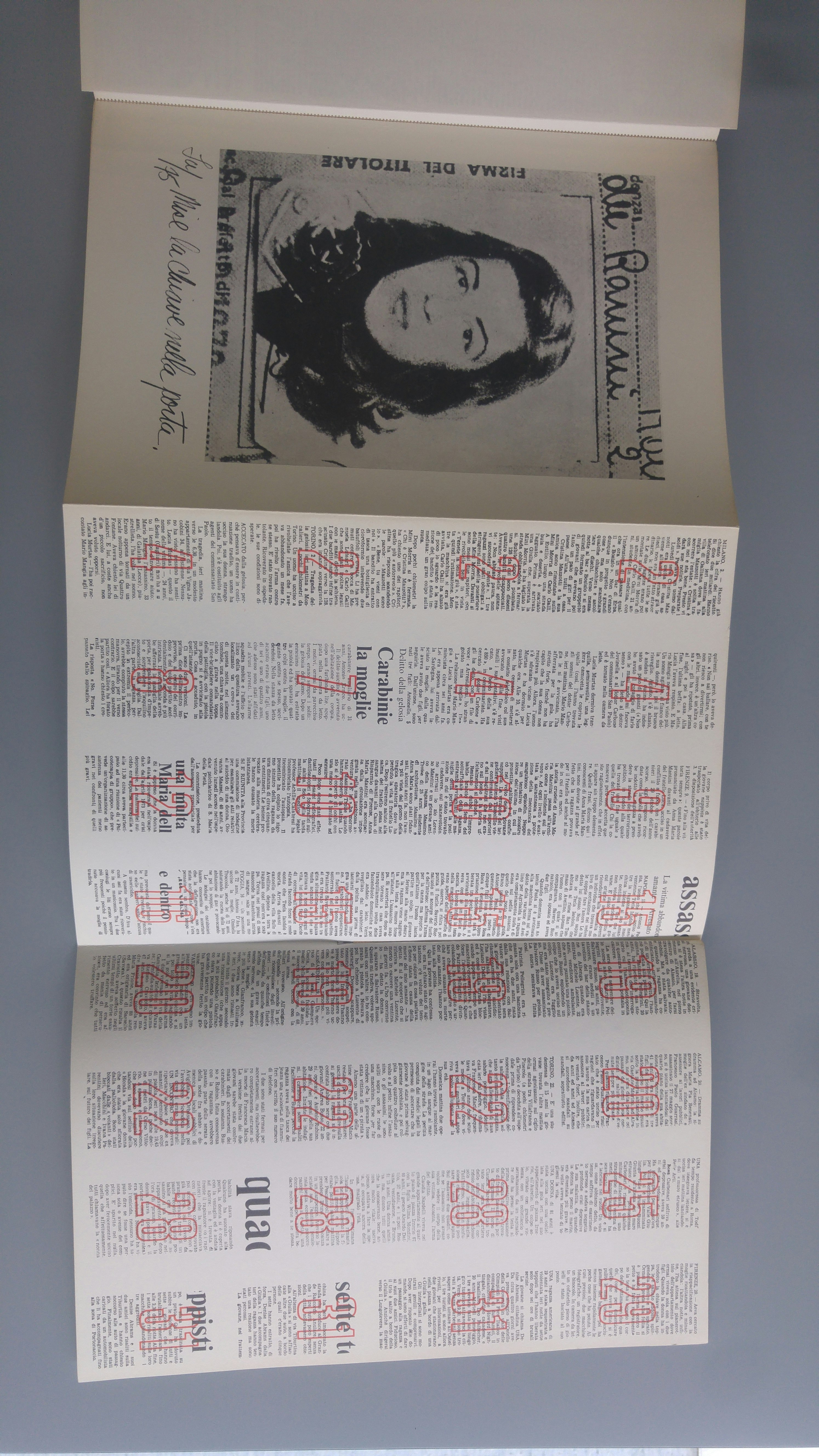

An Album of Violence and

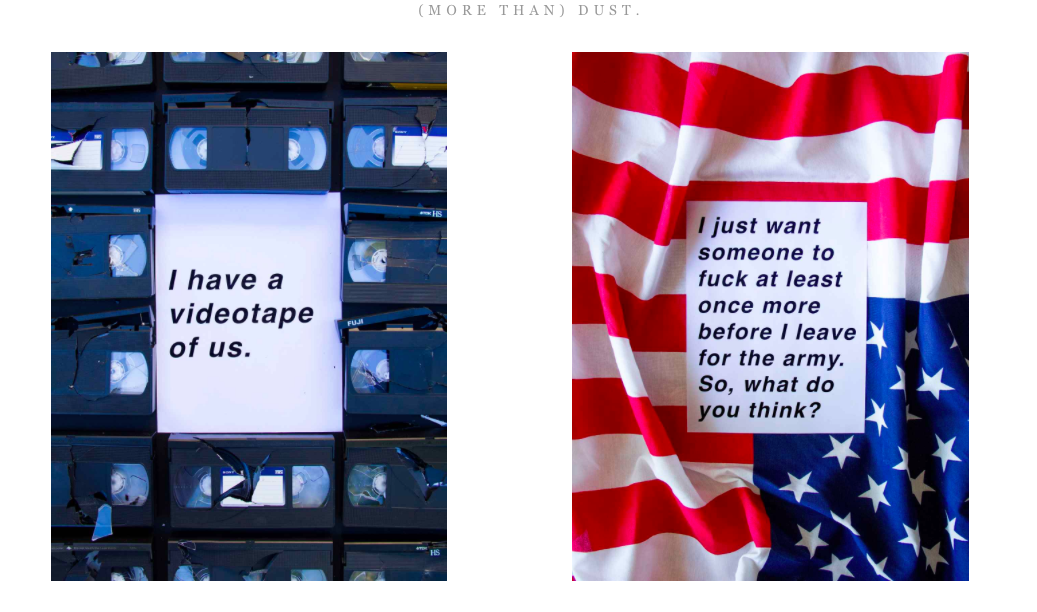

(More Than) Dust share a similar approach of thinking about violence through appropriating and deconstructing the language of the perpetrators, hence the title of this essay “Linguivore Species” to underline the relationship between scripto-visual language and credibility as women’s defence weapon to re-appropriate their abused identities. The title also pays homage to Khairani’s collection of poems,

Indigenous Species, where a young girl “abducted and smuggled aboard a boat bound upstream on an Indonesian river, through a landscape scarred by ecological destruction and historical greed […] may yet save herself”, if, through her indigenous condition, she can root herself back into its landscape and languages.

[13] Equally, by appropriating and subverting the perpetrators’ words, through image-text intersections, the abused women of Oursler and Oliveira boldly demystify the violence they suffered and sarcastically reaffirm their credibility. I believe it is no coincidence that they opted for a scripto-visual language that combines images and words. Photo-text experiments in the 1970s, such as those of Barbara Kruger and Victor Burgin, partly aimed to bring into the art world and market works that addressed political, semiotic and psychoanalytical issues to deconstruct the mainstream ideology of their contemporary society. In terms of ‘Photo Text Data’, Burgin’s 1976

Possession poster is a very interesting pre-Internet example, in which the words “what does possession mean to you? 7% of our population owns 84% of our wealth”, presented with the source of the statistics

(The Economist), and an image of a wealthy white western couple in sensual effusions in between question and answer, intentionally confuse sexual connotations with inequality issues. Oursler’s and Oliveira’s approach is loosely reminiscent of Rosler’s

The Bowery in Two Inadequate Descriptive Systems, as it is plausible that both Oursler and forty years later Oliveira opted for dichotomies of image and text, to overcome the inadequacy of each medium alone when dealing with such a delicate and traumatising issue.