Case Study: Teresa Margolles and Fernando Brito

Text and research: Matthias Pfaller

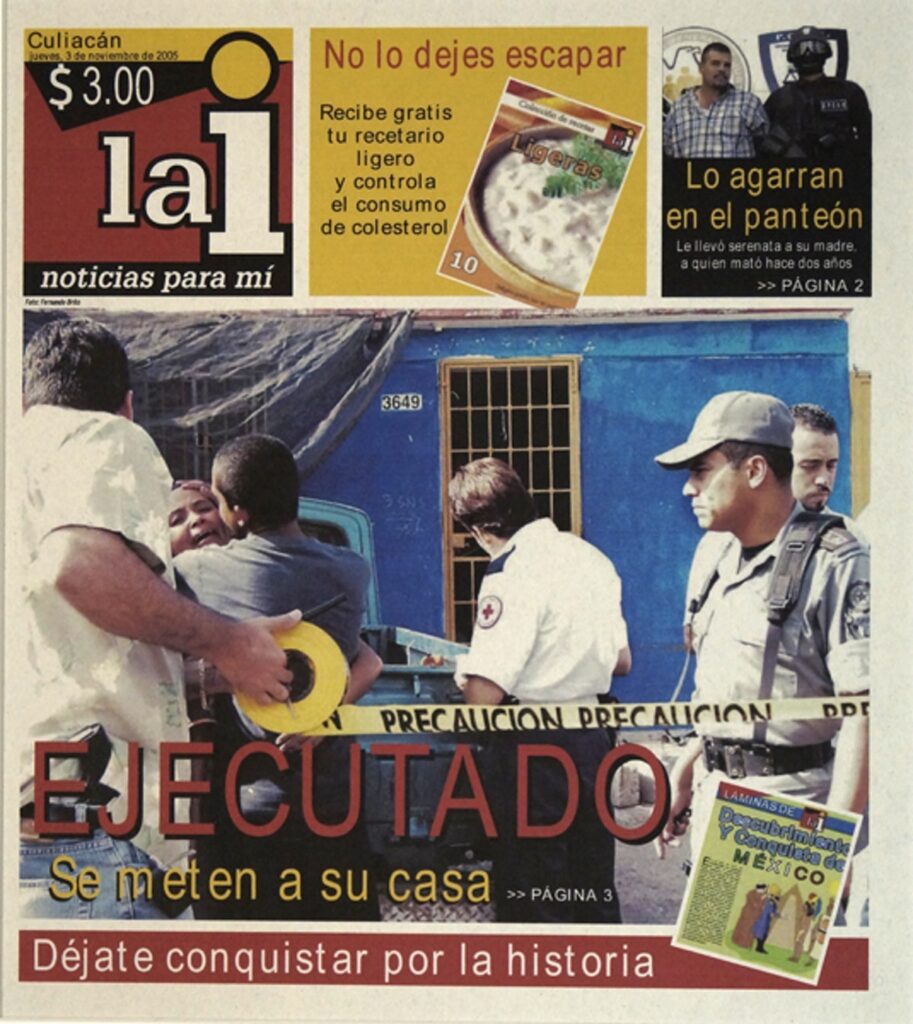

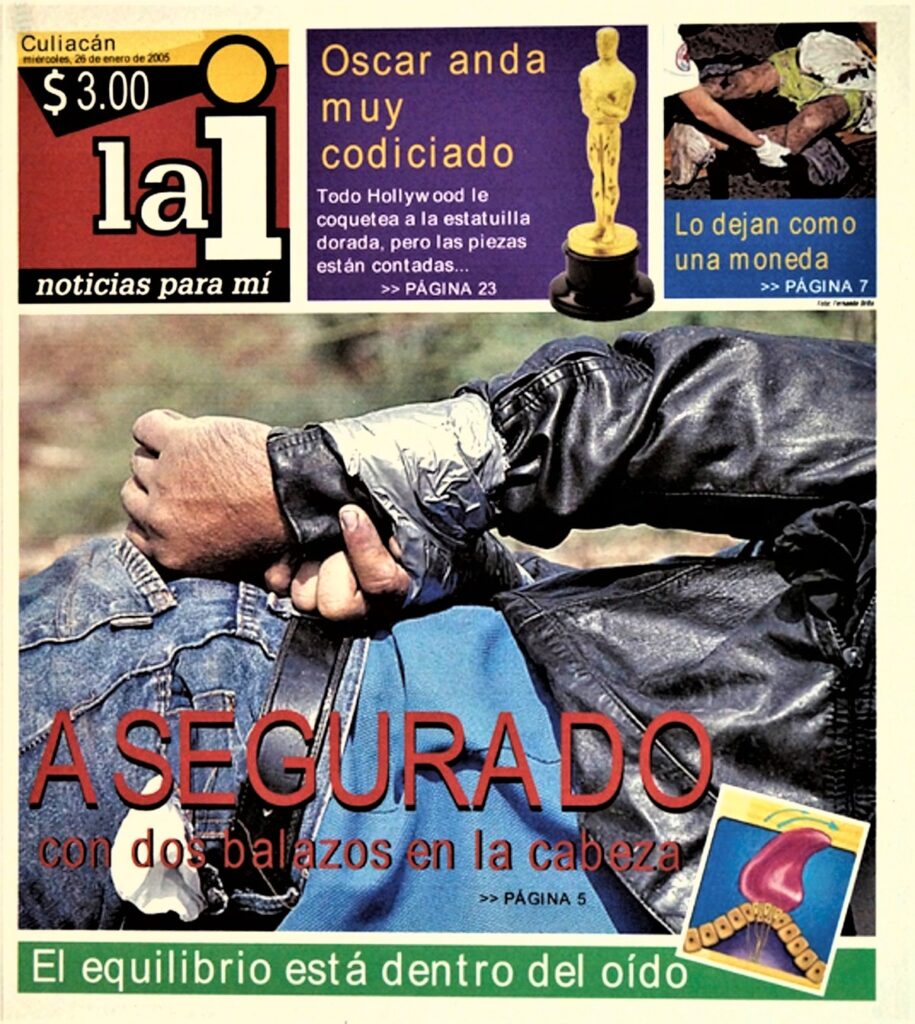

In 2012, Fotomuseum Winterthur staged the exhibition STATUS – 24 Contemporary Documents, which explored the status of the photographic image as a carrier of truth and information and investigating its very own mechanisms as part of today’s multi-media environment. One series shown in STATUS was Front Pages of La i by Mexican artist Fernando Brito (*1975). Brito used to work as a photojournalist in the city of Culiacán near the Pacific Ocean in Northern Mexico, where the daily newspaper La i regularly published his coverage of street murders associated with organised crime. The exhibition showcased six issues published between 2005 and 2008 with images by Brito on the cover. In contrast to many of his colleagues, Brito takes a different approach to reporting about the rampant violence in his city by picturing the dead in a dignified way.

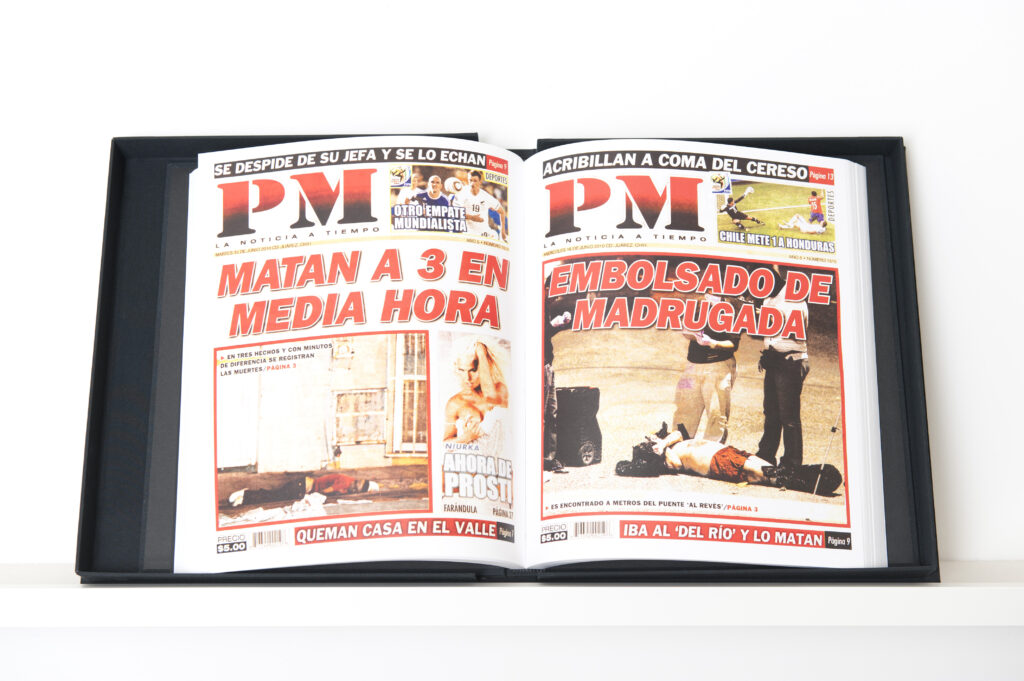

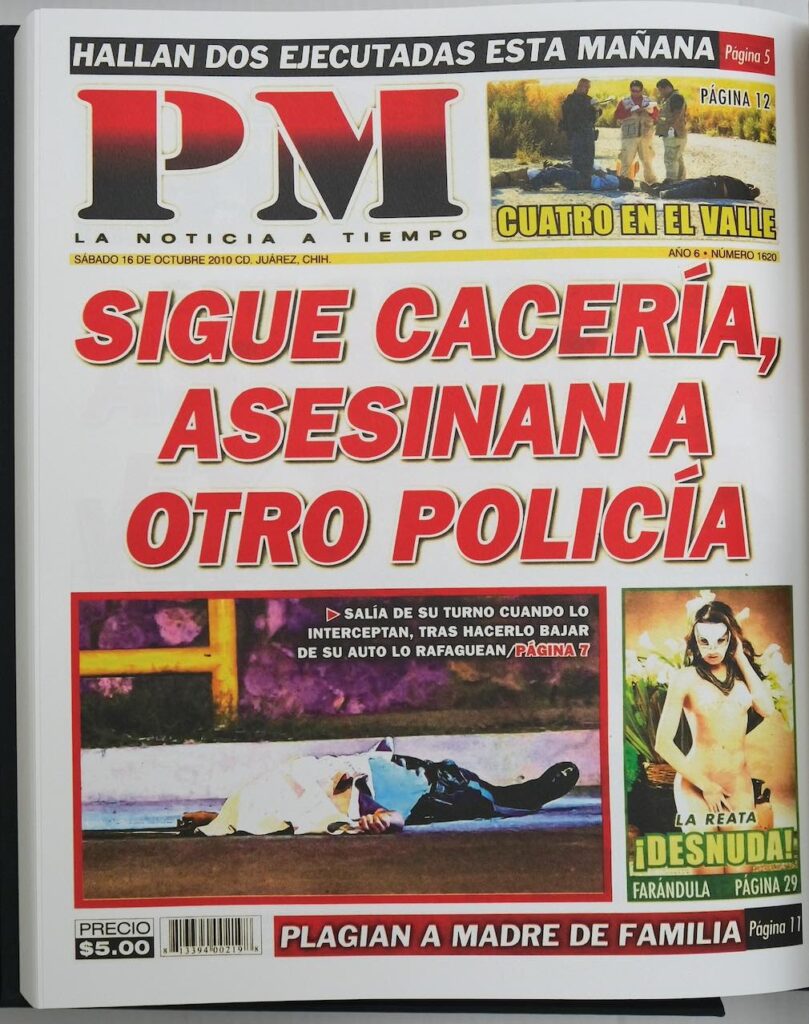

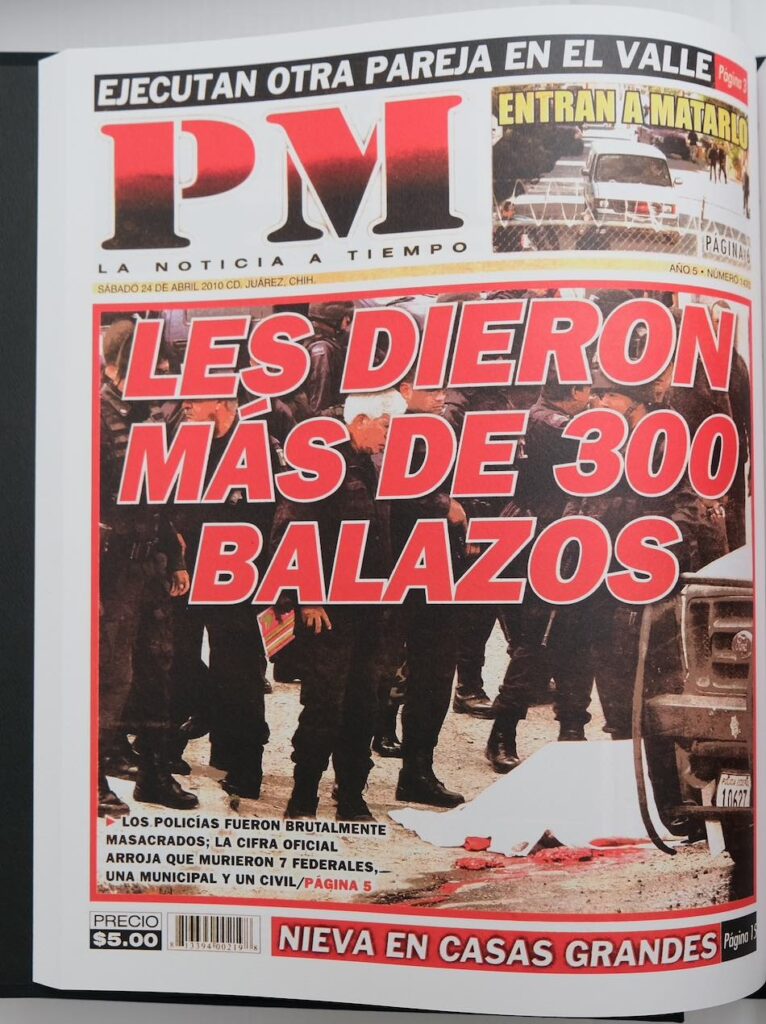

Also in 2012 and in connection with the line of inquiry of the exhibition STATUS, the museum acquired the artwork PM 2010 by the Mexican artist Teresa Margolles (*1963). In a heavy book enclosed in a black case, Margolles put together 313 front pages of the daily newspaper PM based in Ciudad Juárez, a Mexican city on the border to the United States. The covers were published throughout the year 2010, during which drug gangs and police killed more than 3’000 people in that city alone, and which has made history as the most violent year in the Mexican War on Drugs. Accordingly, the title pages of PM show horrific crime scenes with often explicit content. Margolles’ collection of the newspaper pages has not only become an archive of these events, but also an interrogation into the political structures of drug violence and the representation of death.

The two works, both in the collection of Fotomuseum Winterthur, address the unbearable cruelty and sorrow that crime has brought to Mexico. They do so through very different artistic strategies and raise different ethical questions, but always remind us that his had been the everyday life of the people of Culiacán and Ciudad Juárez. Thus, as a Swiss museum, we ask ourselves: how can we appropriately show these works? How can we respect the sensibilities of the murdered, their relatives, and our visitors? More specifically, we continue to ask what makes Front Pages of La i and PM 2010 an artwork, and what happens when conflicts enter the museum space in Europe where visitors might have very little or no knowledge of the everyday life in Latin American countries? To what extent is the depicted brutality neutralised or even aestheticised when presented as an art installation? What kind of information do we need to provide as curators and art educators to understand and communicate the message of the work?

This case study aims to explore Front Pages of La i and PM 2010 from several perspectives: their material composition, the topics that the works raise, the context of the artists’ practice, the cultural and political debates in which they are embedded, the presentation in a museum, and their reception in Europe. In particular, we are interested in the media of the newspaper and photojournalism; for instance, in terms of how Brito’s work is determined by his professional practice, and how Margolles uses the method of appropriation to turn vernacular material into art and ultimately, into an archive. Moreover, we thematise the works’ explicit topics of death, gendered violence, the body, and narco culture. Taking into account the mission of our museum, we ask ourselves how we exhibit images of violence and what kind of discursive practices they require. Rather than considering Front Pages of La i and PM 2010 local Mexican phenomena, we reflect on the geopolitical structure of global capitalism, neoliberalism and coloniality that connects us in Switzerland directly with the situation in Culiacán and Ciudad Juárez.

By inviting the artists, experts and participants from different fields to speak about these issues, we multiply the perspectives on works in our collection. We include different voices in order to forego a specific, limiting curatorial stance, and instead present several ways in which these pieces can be discussed and exhibited.

WARNING: This presentation contains images of explicit violence.

Description of the Works

Fernando Brito’s work Front Pages of La i in the collection of Fotomuseum Winterthur are actual copies of Culiacán’s daily newspaper La i where Brito’s work as a photojournalist appeared on the cover between 2005 and 2008. Thus, we see the images in an applied context, in which they serve the specific function of conveying and illustrating news to a large local audience. The headlines of the killings are framed by other news, be it trivia, such as Jennifer Aniston’s beauty secrets or cholesterol-free recipes, or more serious issues, such as reports on captured criminals and an introduction to the Mexican constitution.

Before Brito started to work as a photojournalist, he says that he was not interested in what was going on in and around his hometown. Yet, by photographing the crime scenes, he he began to understand the complexity of the murders embedded within structures of organised crime and governmental involvement. Still, he could not work freely but was bound by unwritten rules of what is allowed or not to be published. He states that “journalism in Sinaloa is so hushed because there are definitely higher powers that shout us down.” Reports of crimes never develop into larger journalistic investigations for fear of being tracked down and killed, and thus remain a mere chronicle of the events. Moreover, the self-proclaimed mission of La i is to be family-friendly and not explicitly show dead bodies as is common in other yellow press papers. Adding to this, their audience is local, that means that the news have a direct impact on the readers’ lives as the murdered are part of their community. Comparing his work with other photographers, Brito is explicit about his ethics: ‘You can have your hardcore photographs, but that is not what I want to show, that is not what I want the family of the killed to see. We must have respect, and this is the responsibility of every photographer.’ His photographs therefore focus on details or the scene around the corpse and almost never show the dead bodies entirely. They do not amount to forensic evidence but tell the stories around the murder, with police investigating, relatives gathering and weeping together and laying down flowers. Brito’s stance comes from a place of deep sympathy with the victims and their families: ‘I am not a machine and seeing this pain affects me.’ Precisely this personal connection goes against the common reception of crime reports in Mexican society, where the dead are usually considered culprits as people think they must have done something bad to deserve their fate.

With his crime scene photographs, Brito has made second place at the Sony World Photography Awards (2012), and third place of the World Press Photo Award (2011). In addition, his work has been shown at artistic festivals, such as PhotoEspaña, and commercial art galleries. For Brito, in the beginning this success meant a deep moral dilemma, as he felt his work was often limited to questions of aesthetics and that he was profiting from the death of other people. However, eventually he has come to the conclusion that his fame actually means a moral obligation to continue to denounce the social and political situation through his work (information and quotes in this and the previous paragraph are taken from Migues, Testigos presenciales).

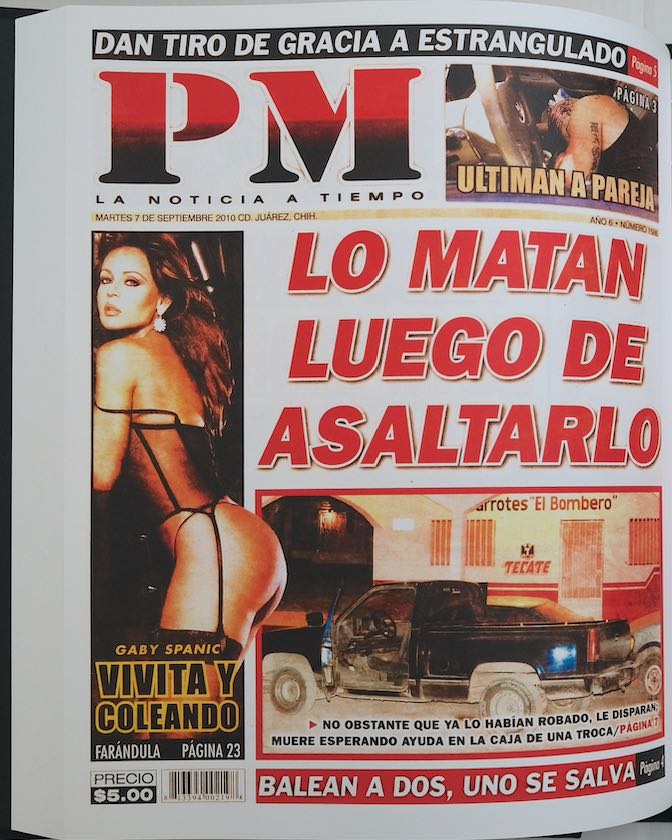

Teresa Margolles’ work PM 2010 is formally very similar to that of Brito’s. It is a collection of front pages of the newspaper PM of Ciudad Juárez, which resemble La i in design and content. Photographs of crime scenes make the headlines, surrounded by bikini models and trivia. However, Margolles’ work is more conceptual in that the artist did not participate in the production of any part of the newspaper, but collected every front page for the entire year 2010 and transformed the single pages in two displays, one as a massive wall-filling presentation of the framed covers, and the other a bound book, a copy of which is in the collection of Fotomuseum Winterthur.

The yellow press newspaper PM is ubiquitous. It is sold on plazas and street corners across the city and finds a variety of uses from wrapping food to building piñatas. As Margolles says: ‘It is very popular, but although you might not want to read it … you touch it, you see it. It is impossible to negate what is happening in society.’ Despite the newspaper’s wide distribution and reception, Margolles’ practice of collecting is significant as the material is at the same time highly ephemeral. The newspaper itself becomes obsolete after only one day, and the publisher does not keep an archive and destroys unsold copies after three months. Thus, PM 2010 becomes an archive of the most violent year in recent history in the North of Mexico with an overwhelming amount of details and proximity to the people’s lived reality: ‘it was our daily life. It was what you woke up with, what you lived with, what people of Juárez ate breakfast and went to school with. While you were sleeping, that was what happened in another place.’

The photographs that appear in PM differ significantly from the ones that Brito published in La i. The crime scenes are similar, but PM decided to accept images that show the deceased close-up and in gruesome detail, often isolated from the bigger scene of police officers and relatives. The horror of the killings is laid bare in its most painful and, problematically, its most spectacular moment. In an interview from 2014, Margolles reflects on this work: ‘For me, PM is a very difficult piece. I have a hard time thinking that this is what happened … It appears to me like fiction.’ The insufferableness of the violence becomes incredible with distance, yet despite the newspaper’s sensationalist reports, the killings are a ubiquitous reality. Margolles takes the entire front pages of the newspaper and does not alter or censor any detail. The lurid language and images thus continue to exercise their effect on the viewers of her work, and with some distance to the events, turns the attention toward the discourse itself. Similar to Brito, she has doubts about the ethical implications of this practice, yet reaches the same conclusion: ‘Sometimes I would not want to have to use blood, to be so direct, but it is necessary.’ (Information and quotes in this and the previous paragraph are taken from Margolles, “El cadáver”, ABC Cultural).

Authorship, Appropriation, Commerce

Brito used to work as a professional photojournalist and now as an art photographer and therefore claims authorship over his photographs. In the making of his work, he invests great care in the construction of the images. Brito never manipulates his photographs by moving objects or people around. He chooses specific angles and frames the scenes so as to include the elements that appear important for his intention to tell a story.

After taking the photographs, Brito’s two professions offer him different possibilities. As an artist, he can decide how his photographs are presented. As a photojournalist, however, he had limited control over how his work is contextualised in the news. The audiences, too, vary greatly. While his exhibitions in galleries and museums are seen by a limited amount of people with specific interests and social backgrounds, his photographs in La i were seen by thousands of people from his hometown where the events happened. Therefore, when the work was acquired for the museum by then co-director and collection curator Thomas Seelig, the question was whether the core of Brito’s work consists in producing ‘images for the wall’ or ‘images in their original context and use’. Ultimately, after discussing this with the artist, the work has been exhibited in the form of the actual newspapers (from a conversation with Thomas Seelig).

In this way, Brito’s artistic and journalistic practice merge, and the status of the photographs as art is conflated with the quotidian of the newspaper. Thus, despite Brito’s authority as the maker of the photographs, the question of authorship is more complicated and must be recognised as multiple in nature. Embedded in the newspaper, the photographs’ meaning is extended by their context, while at the same time Brito’s stance as an author influences how the reports are perceived by the audience.

In a similar double bind, some critics state that Margolles ‘acts more like a journalist than an artist’ in that she transmits the news from Ciudad Juárez to a greater audience and thus informs them about the current situation in Mexico. Yet, while she did collect all the newspaper covers of one year for PM 2010, she limits herself to the strategy of appropriation without any further artistic intervention. She is not the author who makes the decisions as to how depict and describe the murders. Rather than producing the representation of the news herself, her practice questions the way the news are produced, that is, she is taking a step back to reflect on the whole of news, images, text, and circulation.

In the compilation of 313 title pages, the sheer mass of events, stories, and images becomes graspable. Thus, what the editors of the newspaper select as the news of one issue on one particular day in a more or less comprehensible form, turns into an overwhelming amount of information. In this synopsis, certain dynamics are revealed. The thousands of murders that were committed during the year 2010 become repetitive, which is why the photographs as well as the language are consistently scandalous, emphasising alternating but always horrifying circumstances of the killings. The news have to stay new to create attention, that is, different from the normal, which demands new ways of reporting. This, however, becomes almost impossible in a city where murders had become normality.

Both PM 2010, as a conceptual work of art, and Front Pages of La i, in its format, shed light on the commercial side of journalism, which is as much of a business as a way to learn about the world. Thousands of copies of a newspaper must be sold to finance the production of the news. The murders are news, and the news are sellable content. Thus, violence and death are a vital part in the value creation cycle of journalism. The works exemplify ‘how the people – or better said, their assassinated and mutilated bodies – had been converted into a currency in the exchange of a sinister symbolic market, based on the dramatic reality in which the life of the people always valued little’ (Barenblit, El testigo, 11). This ‘exchange value of the object’ is at the heart of the works of Margolles (Jauregui, Teresa Margolles: muerte sin fin, 139), and inherent in Brito’s former profession as a journalist.

Representation of Death

One fundamental aspect of Brito’s and Margolles’ work is the representation of death. Yet, rather than turning it into an ephemeral spectacle as it happens as a news item, both artists reveal the conditions of the deceased person herself and her community. The newspapers employ a paradoxical strategy of depicting the dead for maximum show but at the same time partially conceal their identity so as to retain some sense of respect and journalistic integrity. The result is an unfortunate exposure of the sorrow of the dead and the family while abstracting it into an anonymous, isolated event. Moreover, the ephemerality of the daily news and its material disposability cause a second death, doomed to oblivion. The artistic practice of Brito and Margolles, in turn, reinstate memory and thus dignity. As Gabriela Jauregui writes, the work of Margolles points out the trace of the living to the corpse, and by bringing the corpse into the gallery or museum, she kills the organic aspect of the corpse and brings it back to life as an object (Jauregui, ‘Nekropolis’, 146). The artistic transformation of the dead into images – portraits – turns the objects of spectacle into subjects of their own tragic story. Brito and Margolles, either by photographing the dead or preserving their last photographs and making them a work of art, complete the personal archive of the deceased, as a tribute to their life.

Moreover, the artists explore what is implicit in the murders, but never explicitly addressed in the newspaper reports. As Margolles states, ‘With the deceased body, it’s not that you just approach it and nothing else. You approach a whole community. The corpse is surrounded by what it was, a neighborhood, a village. The dead body always comes with something’ (Margolles, “El cadáver”, ABC Cultural). Through this perception of the body as embedded in the entire social fabric, the work of both Brito and Margolles expand the representation of death to society. Not only the photographs of the desolate crime scenes in run down neighbourhoods, industrial areas, or surrounding landscapes of agriculture or ‘non-places’ speak to the degradation of life. The headlines of utterly cruel acts of violence, too, refer to a development of brutalisation and moral disintegration. While Jauregui refers to a different piece by Margolles, her insight perfectly fits the two works discussed here: ‘By representing the poverty, social unrest, crime, overpopulation, pollution, and the violence of the capitalist metropolis, it transforms that metropolis in a necropolis. Thus death of the organic body also represents death in the body politic. Her work literalizes this metaphor – death, after all, represents the absolute change of state (change in the State)’ (Jauregui, ‘Nekropolis’, 148. She quotes Lisa Downing, Desiring the Dead, Oxford: Legenda, 2003, 39). The dead bodies are not torn out of society, they stand in for the whole community, its organisation, rules, and ultimately, survival.

Guilt and Gendered Violence

The formal similarity of the works of Brito and Margolles in the collection of Fotomuseum Winterthur is not a coincidence or practical outcome of the fields in which the artists work, in photojournalism or appropriation art. The specific appearance of the yellow press newspaper reflects specific societal structures which the artists criticise. First, the representation of the murders is ambiguous at best; in many cases, however, it already presumes some degree of guilt. As Brito says, ‘the problem of the photographs in sensationalist newspapers and some violent death is that we justify the murder and criminalise those who appear in the images.’ The logic here is that the killing must have had a reason, and the dead person must have done something bad which incited someone else to take revenge. This view is particularly morally corrupt since, as Brito continues, murders in Sinaloa have often been random, and gangs made it a ‘sport’ to kill innocent people (Migues, Testigos presenciales).

Second, through the layout of the newspaper front pages, the images of the dead are juxtaposed to images of the living, that is, those who apparently deserve to live. In many instances, the photographs are of bikini models and famous, barely clothed actresses, who satisfy a macho desire of sexual activity. The immediate contrast of images of the aestheticised female body and the mutilated corpses amounts to a celebration of life and death in their respective extremes. It is an abysmal schism between the lust for beauty and the abject. What unites these desires is the objectification of both the models and the dead, in which neither is bestowed the respect of a subject, let alone an individual.

Yet, the glorification of female beauty on one side of the cover page does not mean that women are spared the horrid events depicted on the other side. Women are disproportionally affected by violence. A survey by UN Women in 2018 found that in Mexico, at least 6 out of 10 women have experienced violence, 41.3% have been victims of sexual violence, and every day, 9 women are killed. The dehumanisation of women as objects of male desire in the photographs is an immediate cause for the violence inflicted upon them, as they are seen as nothing more than bodies to possess, rape, and dispose of. This structure from admiring to depreciating women is illustrated in perfect sequence on the front pages. In addition, the same logic as described by Brito above applies to the photographs of killed women reproduced in the press: public discourse suggests that only ‘the bad women’ were victims of kidnappings and murders (Rosauro and Ruz). The step from being a model to a corpse is again justified through a quick judgment of their own behaviour, rather than revealing the structural reality and catastrophic effects of sexism in Mexican society.

What is more, the violence against women is not only belittled but purposefully overshadowed and invisibilised by the so-called ‘war against the drug trade’ and women who have organised to fight against gendered violence have been threatened (Rosauro und Ruz). In this environment where women are in concrete danger and are prohibited to speak up, the work of Margolles gains particular weight. The artist herself addresses this issue and her own position in society and the art world: ‘Of course, my status as a woman in relation to what’s been termed an all-male aesthetic has affected my artistic practice. Of course, my status as a woman in the world affects the ways in which I work’ (quoted in Amy Carroll, 107n10). The heavily male-focused makeup of the newspapers is part of how life and death and individual dignity are conceived by society and must therefore be part of the assessment of the situation of women in Mexico and the aggression against them, physically and symbolically. This is an ongoing process which goes beyond the time frame of the works of art presented here: a few years after making PM 2010, Margolles reflects on the conditions in Ciudad Juárez, which though it has improved, ‘has not changed even a bit is the situation of the women’ (Margolles, “El cadáver”, ABC Cultural).

Interviews

Dr. Elena Rosauro is a postdoc researcher at the University of Zurich and co-curator of the independent art space la_cápsula in Zurich. Her book History and Violence in Latin America. Artistic practices, 1992-2012 (CENDEAC, 2017) offers a survey of artworks dealing with the issue of violence in the context of Argentina, Brazil, Colombia, Mexico, and Peru. She has also published specifically on the works of Fernando Brito and Teresa Margolles.

In this interview, Rosauro recapitulates the political and economic context of Mexico in the 1990s, which saw a massive transformation of industries in the border region with the USA after the implementation of the NAFTA free trade agreement in 1994 and the parallel rise of drug trafficking. However, more than being a local problem, global drug consumption, particularly in rich countries, feeds into the staggering violence occurring in Mexico. Regarding the artworks produced around this issue, she warns about branding them as ‘violence porn’, which reduces the works by Brito, Margolles, and many others to a spectacle equally consumed by a privileged contemporary art scene in the North Atlantic. She points out the feminist critique in Margolles’ works and the difference of the images of violence in Mexico to pieces produced in the Southern Cone.

Fernando Brito is an artist who works on the repercussions of violence in Mexican society. In this interview, he recounts his personal experiences as a photojournalist in Culiacán during the hot phase of the War on Drugs with thousands of victims. While his coverage of countless murders put him in the danger of death, he felt an urge to find out and communicate what was happening in his hometown. Rampant corruption and an active involvement of the government with the drug lords not only deteriorated politics, but also the discourse around the violence. Thus, the question of whether to show pictures of violence has overshadowed the underlying problem of violence per se. Critical of this discourse, of which he as a photographer and editor of La i had been part, he clearly states that such images must be circulated to denounce the situation. He is equally critical of the reception of his works as an artist, namely the aestheticisation of his series Tus pasos se perdieron con el paisaje by European curators. The mediation of his photographs and the Mexican context to foreigners has always been a challenge, but his wish for his audience outside Mexico is to simply imagine the situation in which these images are what people see and deal with every day.

Sources

ONU Mujeres – México. ‘Día Internacional para la Eliminación de la Violencia contra la Mujer’, 25 November 2018. https://mexico.unwomen.org/es/noticias-y-eventos/articulos/2018/11/violencia-contra-las-mujeres.

Carroll, Amy Sara. ‘Muerte sin fin: Teresa Margolles’s Gendered States of Exception’, TDR 54, no. 2 (2010), 103–25.

Jauregui, Gabriela. ‘Nekropolis: Die Exhumierung der Arbeiten von Teresa Margolles’, in Teresa Margolles: muerte sin fin, ed. Udo Kittelmann and Klaus Görner (Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2004), 133–51.

Margolles, Teresa. ‘El cadáver debe estar sobre las mesas del mundo del arte’, ABC Cultural, Madrid, 22 February 2014.

Margolles, Teresa, and María Inés Rodríguez. El testigo (Madrid: Centro de Arte Dos de Mayo, 2014).

Migues, Darwin Franco. ‘Fernando Brito. “No soy una máquina y ver el dolor me afecta”’, Testigos presenciales (blog), no date. http://nuestraaparenterendicion.com/testigospresenciales/fernando-brito/.

Rosauro, Elena. Historia y violencia en América Latina. Prácticas artísticas, 1992–2012 (Murcia: CENDEAC, 2017).

Rosauro, Elena, and Adriana Domínguez. ‘Teresa Margolles. Señalar la muerte’, in México en el tiempo de la rabia. Arte y literatura de la guerra, el dolor y la violencia (2006–2018), ed. Alejandro Zamora and Gustavo Ogarrio (Cuernavaca: Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, 2020), 58–75.

Rosauro, Elena, and Tania Sordo Ruz. ‘“Caminar por estas calles, a plena luz del día, da miedo”: representaciones y artefactos culturales contemporáneos de artistas mexicanas sobre el feminicidio en Ciudad Juárez’, in Fracturas de la memoria: un siglo de violencia y trauma cultural en el arte mexicano moderno y contemporáneo, ed. Dina Comisarenco Mirkin (Mexico City: UNAM, forthcoming).

Team Extra #1

Our experimental format Team Extra is an invitation to people from different fields explicitly intended for those without specialised knowledge of art, museums or media. We discuss works from our collection with them in the hope of inspiring new perspectives and involving an array of different voices in our consideration of these viewpoints. The members of Team Extra have a range of experience in key areas relevant to the viewing and classification of the works held by the museum, and the process of exploration is enriched by their take on our collection.

On 5 February 2022, as part of Case Study #2 Fernando Brito & Teresa Margolles, Fotomuseum Winterthur invited Team Extra #1 to attend a one-day workshop. Together we examined issues relating to the representation of violence – a key element in the images of Mexican artists Fernando Brito and Teresa Margolles (both of whom live and work in Mexico). We also considered how these works in the collection can and should be presented and discussed in the museum setting.

Part 1 focused on Brito’s Frontpages of La i and Margolles’s PM 2010, reflecting on the way societal violence is represented in Switzerland and Mexico and in the museum context. In part 2, led by artist Paloma Ayala, the group designed the fanzine Sensitive Content. The visual experiment is the product of Team Extra’s individual and collective experience of the works in the collection at Fotomuseum Winterthur.

The museum would like to thank Mexican Swiss visual artist Paloma Ayala and Team Extra #1 for the time and effort they invested in the project. All the participants live and work in Switzerland. Team Extra #1 are:

Ronan Ahmad, author and cultural worker (Iraqi-Kurdistan)

Cristiana Bertazoni, cultural anthropologist (Brazil)

Alina Silberbach, funeral director and Thanatos practitioner (US/Germany)

Sandro Benini, journalist and former Latin American correspondent (Italy/Switzerland)

Ed Rijks, computer scientist and artist (Netherlands/Switzerland)

Patricia Skirgaila, media scholar specialising in media psychology (Switzerland)

Team Extra workshop: Laura Felicitas Sabel, cultural studies researcher and educator, Fotomuseum Winterthur

Documentation workshop: Thi My Lien Nguyen, photographer and artist