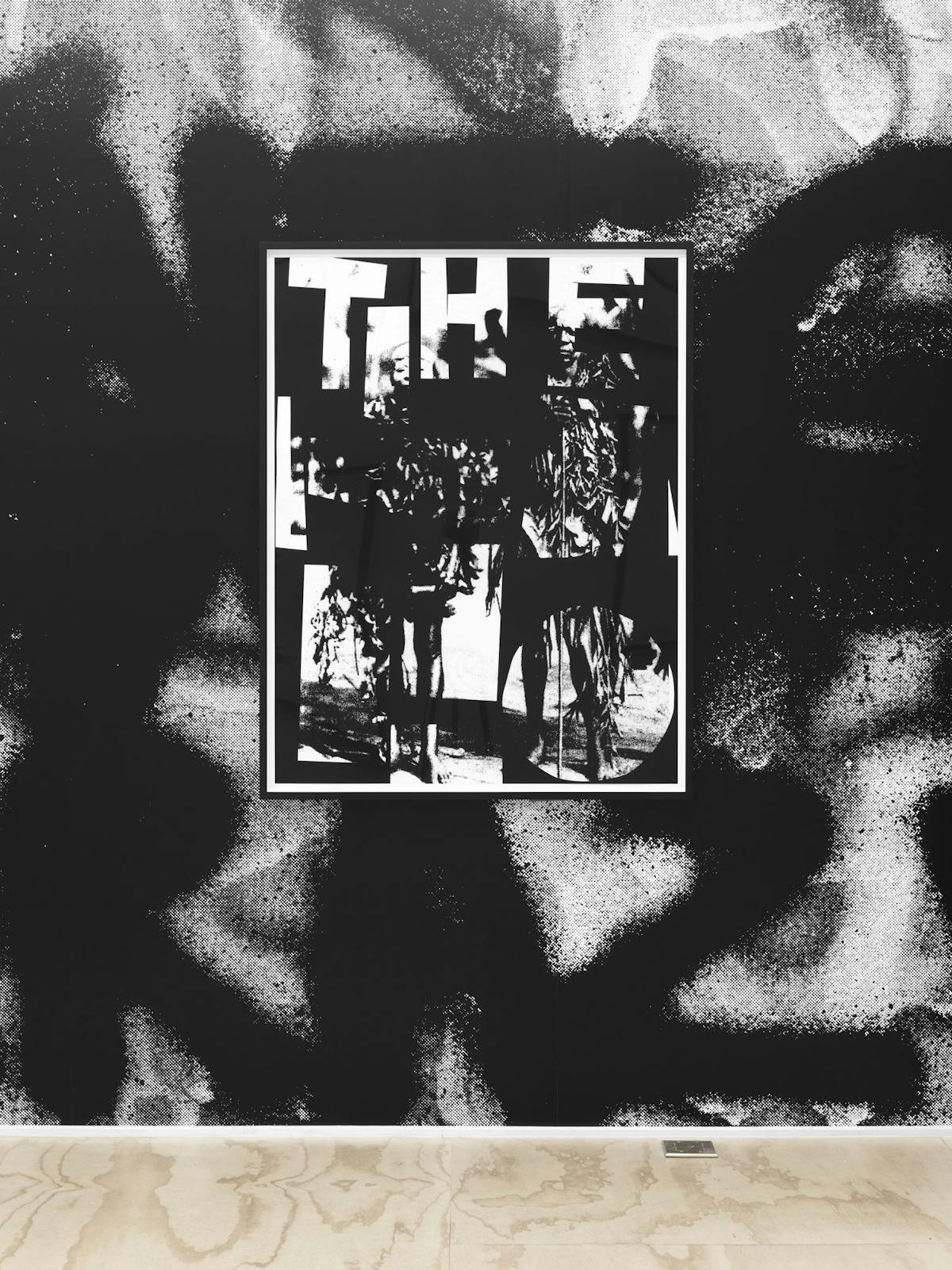

Lumumba tells the history and politics of Patrice Lumumba, the first Prime Minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), whose assassination, reportedly under the direction of Belgian command, came shortly after his appointment. Peck details his migration from Haiti to the DRC (then Zaire) as a boy. His parents migrated as part of a drive to fill the employment gap produced by the withdrawal of Belgium. Peck says of his childhood circumstance: ‘We were Black but we were white. We were different.’ Lumumba, then, is also about navigation. The history of the DRC is recounted to Peck by his mother who was secretary to the Mayor of Leopoldville (present-day Kinshasa). We see footage shot by Peck’s father. However, it is Peck’s voice which guides us through Lumumba’s history in a redaction created by filtering through many different voices. We encounter subjectivity, Peck imaging in the ways which his body allows him to move. We see images of the Brussels airport Peck is travelling through, his plans to travel to the DRC derailed in fear for his own safety. 3 For an in depth discussion of Lumumba: Death of A Prophet, see Laura U. Marks, The Skin of Film: Intercultural Cinema, Embodiment, and the Senses (Durham and London: Duke University Press, 2000). By exposing the redaction which has been forced upon him, seemingly by the Zaire secret service, Peck makes clear the mechanisms and politics which surround Lumumba’s image in the mundanity of an airport.