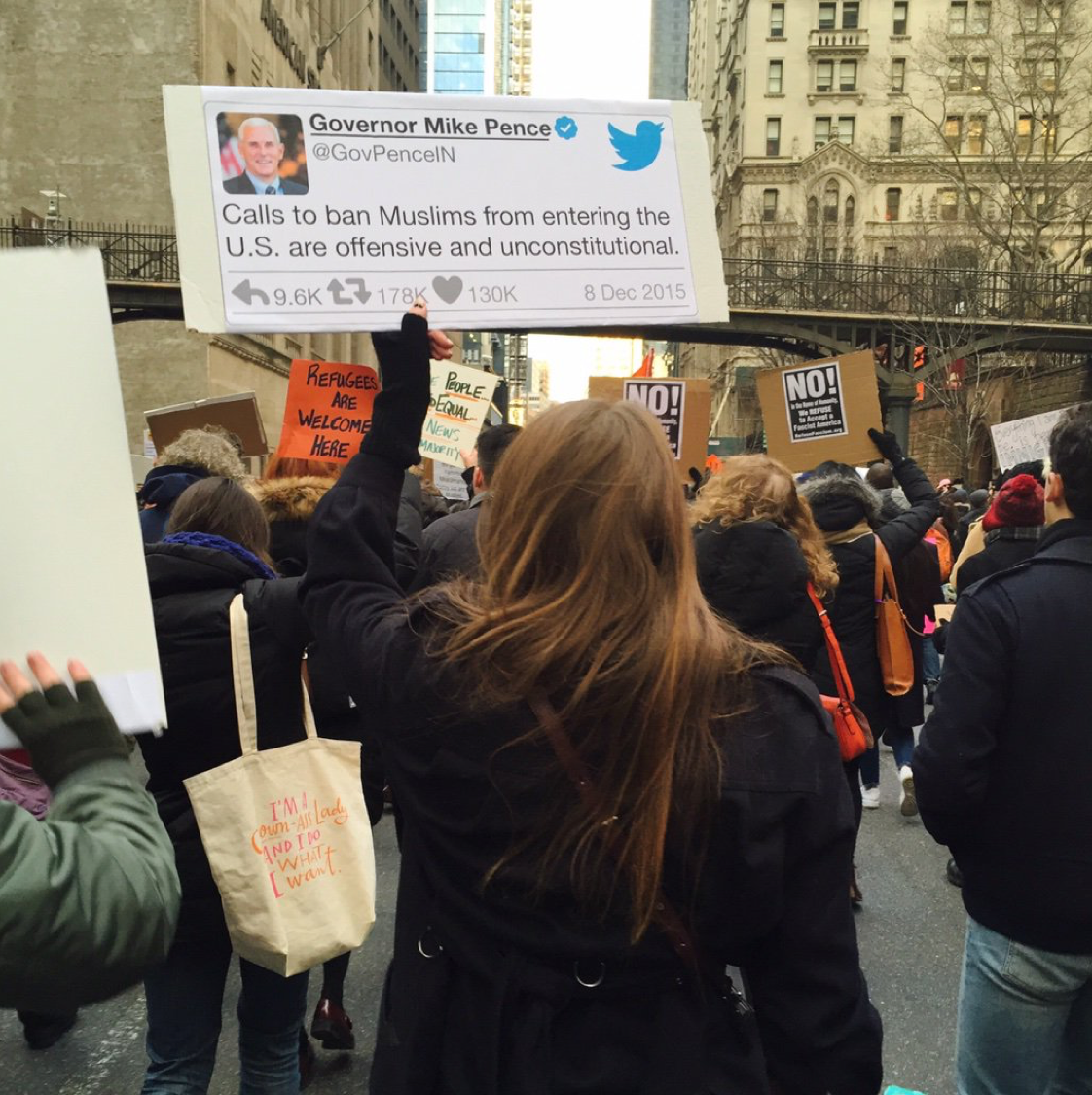

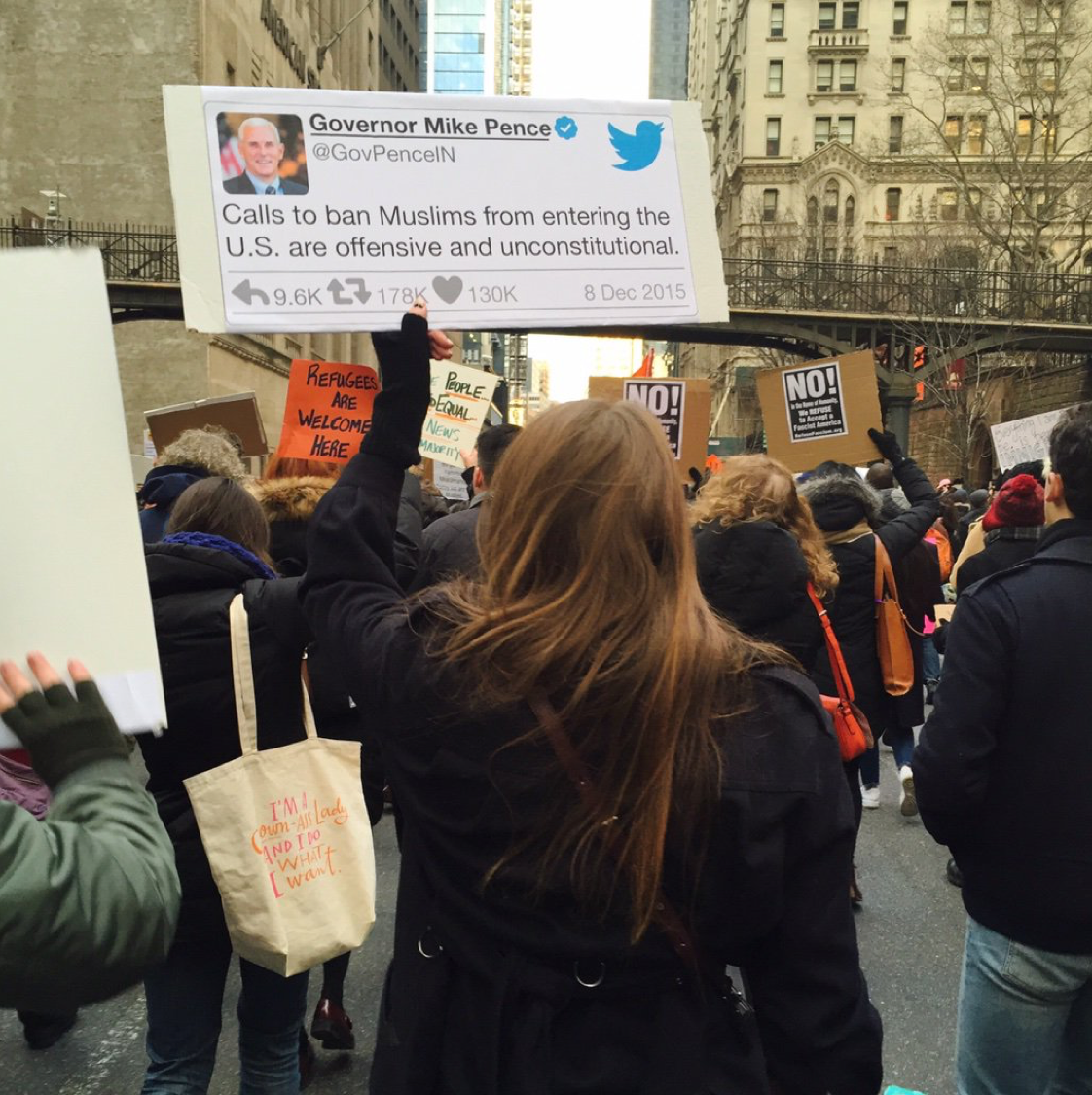

While this practice may be, at best, subcultural, this reframing of the screenshot as proof or evidence has only grown in prominence in the past two decades, particularly with the rise of social media and the ability of celebrities, politicians, and others to edit or delete embarrassing, incorrect, or illegal statements after the fact. 4For a discussion of this evidentiary function in the context of contemporary politics, see Paul Frosh, “Screenshot: The ‘Photographic’ Witnessing of Digital Worlds” in The Poetics of Digital Media (Cambridge, UK: Polity, 2018), 62–92. Screenshots, in this sense, serve an archival impulse. They are a way of proving an action was taken or a statement was made, a way of securing a response in case of its deletion. This gesture seems particularly relevant given our current political climate, but it is also central to the larger project of digital history, as these are the images that will make possible any claim to the existence of cultures, objects, and practices that have been mediated through the screen of a computer. 5Of course, screenshots are just as easily manipulated as any other digital image, and indeed the trend in recent years has been toward applications that allow for the immediate modification of screenshots before they are sent or saved. This would seem to reflect a transformation in the function of the screenshot as an informal and unmediated capture.