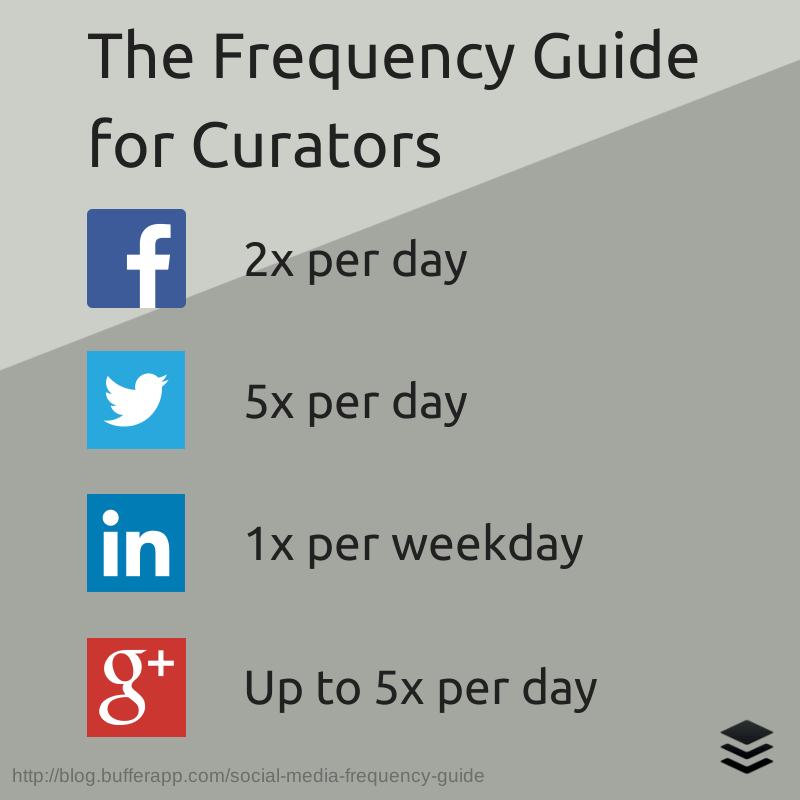

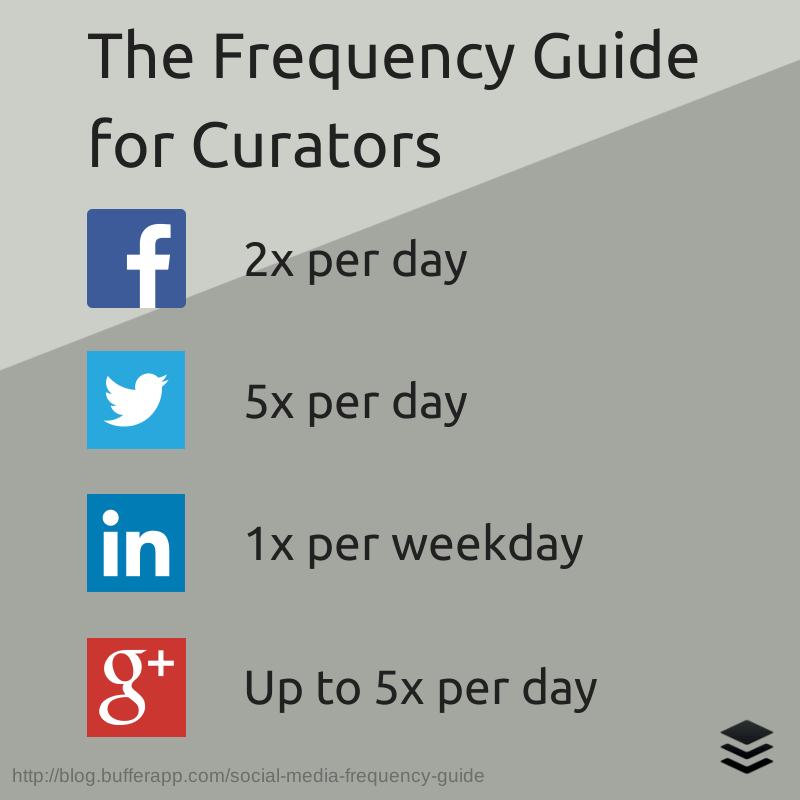

Photography Must Be Curated! takes as its starting point this contemporary condition of cultural hyperproduction and the annexation of curating by digital marketing. Over the coming weeks, I’m hoping to speculate on the vectors between the ‘curation economies’ of the museum, web and cloud. In doing so, I want to sketch a much larger set of issues concerning photography’s cultural value which remains largely unaddressed by those charged with its collection and exhibition. At the heart of the matter – which content marketers exploit – is that the capacity of the singular, enframed image to ‘speak’ and survive as a semantic unit is being exhausted. The digital image – materialised on screen in the cultural form of the photograph – slips past in a series of swipes, likes and volleys. Its liquidity and malleability demands fixity – it demands to be curated, valorised, cared for and shaped into aggregations that in turn generate new vectors of attention and value. Or, put another way: After the massification of photography comes the massification of curating. 1I’m borrowing here from Pedro Alves Da Viega et. al, “Chapter 10: Toward a B-Society Model: The Digital Media Art Experience”, in: User Innovation and the Entrepreneurship Phenomenon in the Digital Economy, ed. Pedro Isaias and Luisa Cagica Carvalho (Hershley, PA: IGI Global, Business Science Reference, 2018), 194–216, here 201: “After the massification of artistic creation comes the massification of curating” (who in turn borrow from David Balzer, Curationism: How Curating Took Over the Art World and Everything Else, 2014).