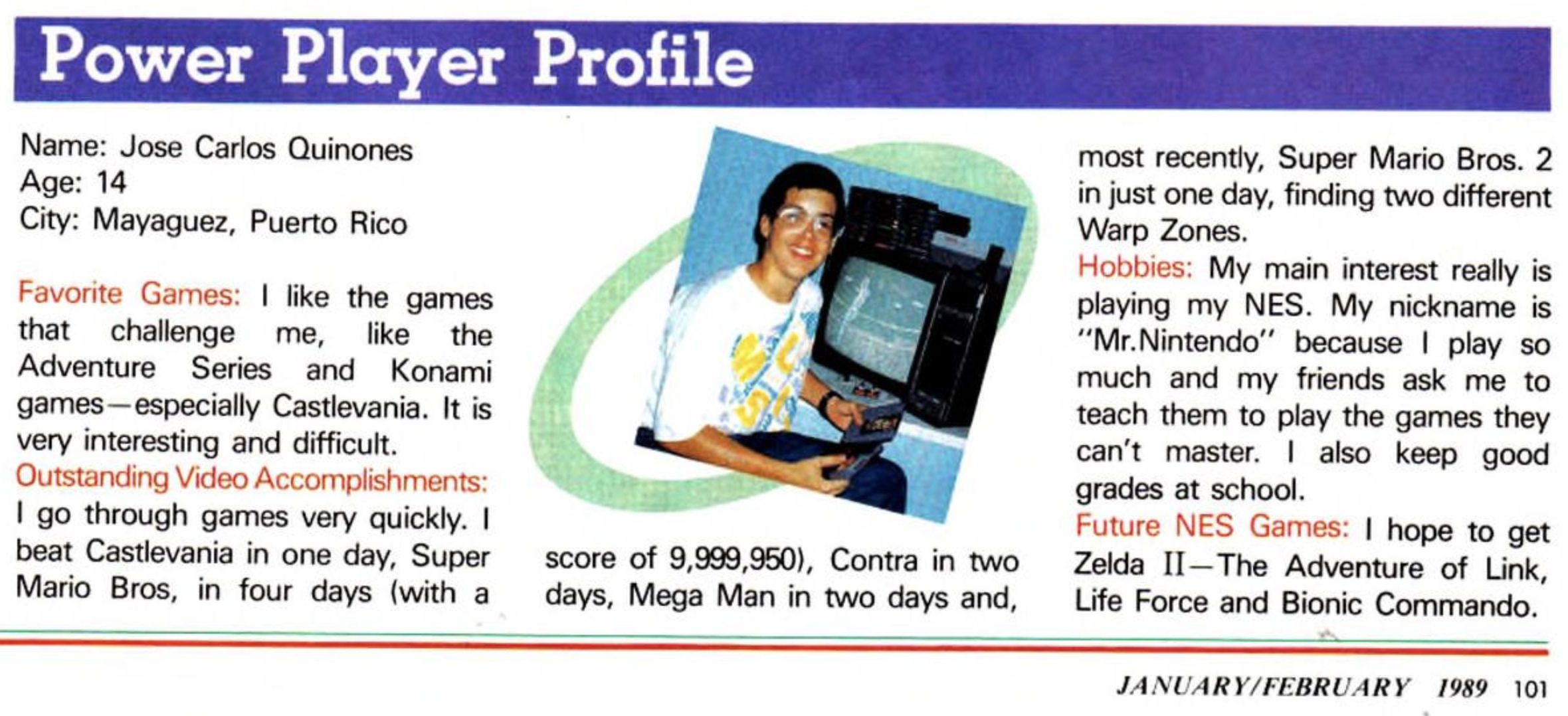

I want to return once more to the question I began with: what exactly do these screenshots capture? On their surface it would seem these early game screenshots capture player skill and elite forms of play that could be marked or proven with a clearly photographed high score, but on closer examination it becomes clear that these screenshots capture cultures of use that are highly non-normative, and which call into question the very idea of measurable or quantifiable skill in play. Take a classic game like

Super Mario Bros. (1985). The NES Achievers page for the game consists exclusively of players who have achieved the maximum score allowed by the game: 9,999,950 points. This number is ridiculous, particularly to anyone who has played

Super Mario Bros. and perhaps doesn’t even recall that the game had a scoring system to begin with. Score in

Super Mario Bros. functions as a strange vestigial component from arcade play, one that has almost nothing to do with the narrative goals of the game. The idea that maximizing score to this extreme demonstrates player skill seems wrong, but if these scores and their corresponding screenshots do not demonstrate skill, what exactly do they capture about the culture of early gaming? While I cannot claim a definitive answer, it seems likely that these scores index a form of non-normative play whereby players

exploit a game glitch to maximize points, with the goal of hitting the point cap of 9,999,950. This mode of play uses point farming as a kind of metagame within

Super Mario Bros. that operates largely outside the game as a consciously designed system. 3Stephanie Boluk and Patrick LeMieux,

Metagaming: Playing, Competing, Spectating, Cheating, Trading, Making, and Breaking Videogames (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017). Nonetheless, while these scores might not tell us about who the “best” players of a particular game are, they do seem to mark a community of practice invested in these strange and surprising forms of play.