Techniques for Secondary Mediation

Screenshots are the snapshots of our computers. They capture the movement and forms of everyday life as it is lived through the interface of a computational device. Given the trend, since at least the 1970s, toward media convergence, in which existing media forms are subsumed and transformed by digitization, today most any medium or practice that can be displayed on a computer screen may therefore be captured as a screenshot. Consequently, it can be difficult to speak of screenshots in the universal, as their application is highly dependent on the cultures of use in which they are situated. Stop reading for a moment and take out your phone. Open up the photo gallery and navigate to the screenshots folder. What do you see? A recipe grabbed before leaving the house to shop for ingredients. Directions to a hotel taken before traveling without cell service. A funny image of your niece calling on FaceTime with your brother. An embarrassing Instagram advertisement you sent to a friend. Disposable images, made in passing, and easily forgotten. Objects to be found months later as you scroll through your phone, wondering why this moment seemed so necessary to capture, asking what these images tell you about the way you use and understand those visual technologies that structure your daily life. Screenshots are perhaps best categorized as one of many vernacular computational practices, in that there is a great deal of variance in how they are used, modified, and disseminated. No one teaches you how or what to screenshot, it is a tool with no fixed application.

In a formal sense screenshots resemble a number of existing technical practices. Photography, most clearly, though what screenshots capture is not the world itself but the fixed visual state of a complex technical milieu in which various media forms are situated – a moment in the life of a machine. That said, there are many other antecedents we might name, image forms and cultural practices that allow for this secondary mediation of a visual medium that is otherwise contained within a window, screen, or a frame. In his work on the slide lecture, now almost twenty years old, art historian Robert Nelson notes the ways that, as early as the mid-19th century, slide projection transformed and formalized the discipline of art history, allowing for the reproduction – in Benjamin’s sense of the term – of the art object elsewhere, taken “not as shadow, projected photograph, or copy of an original, but as the object itself.” 1Robert S. Nelson, “The slide lecture, or the work of art ‘history’ in the age of mechanical reproduction”, Critical Inquiry 26, no. 3 (Spring, 2000), 414–434, here 417. Nelson was writing on the eve of what he imagined to be a massive sea change in the field of art history, as this century-old technology – the slide lecture – gave way to digitization. He laments, “where will the art historian stand in cyberspace, and what codes, disciplinary, performative, or otherwise, will control the content and guarantee the reliability of art presentations?” 2Ibid., 434. Perhaps the screenshot and its codes, both technical and cultural, offer us at least a partial answer.

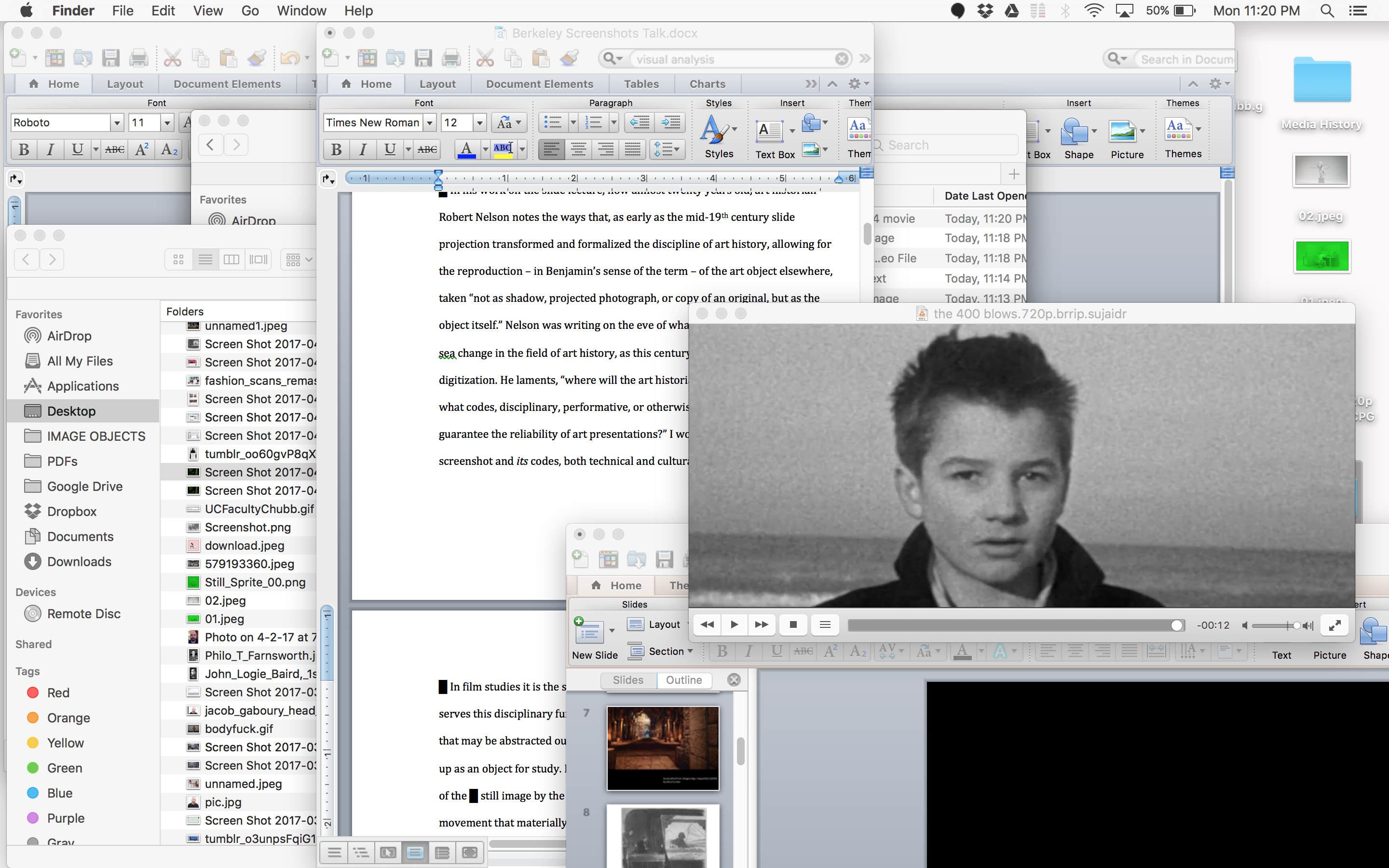

In film studies it is the still, the freeze frame, or the frame enlargement that serves this disciplinary function, allowing for an explicit and fixed visual referent that may be abstracted out from the experience of the cinema itself, and offered up as an object for study. Of course, there is a great deal that could be said of the use of the still image in the avant-garde as a technique that refuses the very movement that materially defines the cinema, yet very little has been done to develop a theory of the still, as Roland Barthes once suggested, such that we might understand it not merely as one part of a greater whole, but as “the fragment of a second text whose existence never exceeds the fragment; film and still […] in a palimpsest relationship without it being possible to say that one is on top of the other or that one is extracted from the other.” 3Roland Barthes, “The Third Meaning”, in Image-Music-Text (New York: Macmillan, 1978), 67. Today it would seem that it is less the single frame of a celluloid strip that serves in this capacity, but rather the screenshot of a digital video file captured in medias res, that is, in the middle of any number of complex operations that contain but exceed the still itself.

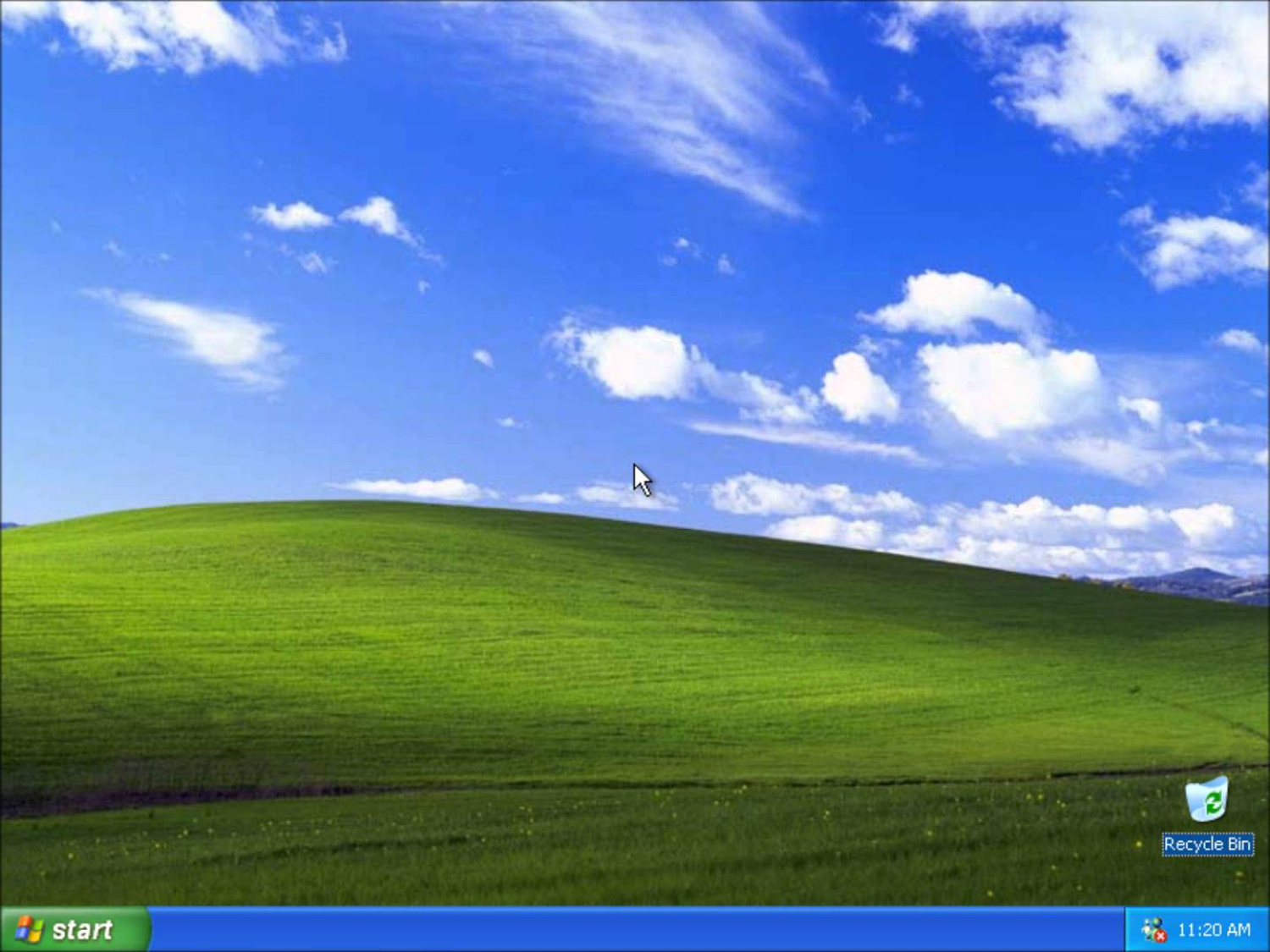

There are no doubt many other media forms we could include in this list, equally offensive to those with an investment in the material specificity of these disciplinary practices. I include these here not simply to inflate the relevance of this work, but because today each of these acts has been replaced or at least augmented in some way by the digital screenshot. Where we once found the snapshot, the slide, and the still we now find the bitmap and its attendant logics. The screenshot here functions as a method for visually fixing and rearticulating an existing dynamic medium, such that it might be made legible and coherent as an object for analysis. Yet doing so necessarily flattens the thick materiality of the medium it captures, preserving it as a static image. The screenshot is in this sense a deeply ambivalent object, at once alienated from the context of its historical production and yet simultaneously central to the very possibility of producing a history that attends to the visual articulation of our digital media technologies. However, if we do hope to engage, and indeed preserve the dynamic topology of our digital media culture, we must embrace this contradiction, redeploying it in the service of new methods for the production of visual knowledge. It therefore seems important to examine the long history of the screenshot and make this anachronistic claim in order to understand precisely how each of these media practices has been collapsed into this single operation, this software gesture, this button: PrtScrn.

To understand this transformation, this series will track the history of the screenshot as a technique for the secondary mediation of the computer as a dynamic visual medium. Beginning with the rise of visual displays for computation in the immediate postwar period, I will track the screenshot as it shifts and mutates alongside the computer in the second half of the twentieth century, from the WYSIWYG printed documents of desktop publishing to the screen selfies and high score documentation of early digital game culture and the photo-objects that populate our modern computer desktops and smartphone image galleries. Tracing the history of the screenshot reveals the many ways we have pictured computation as a technical and cultural practice, and the ways this practice has in turn transformed our relationship to nearly all screen media we encounter today.