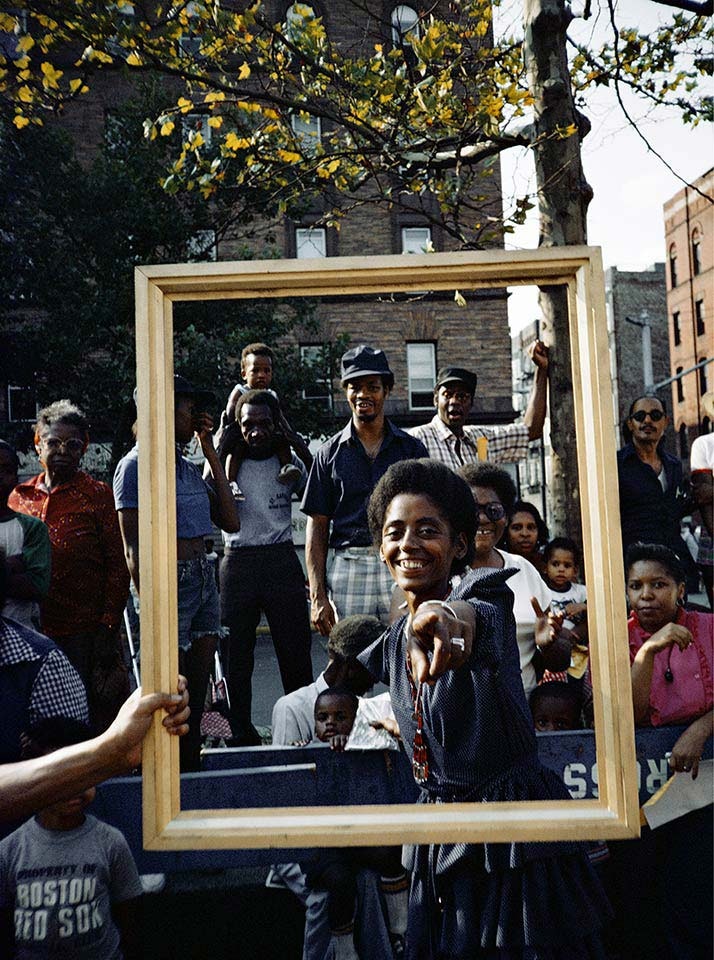

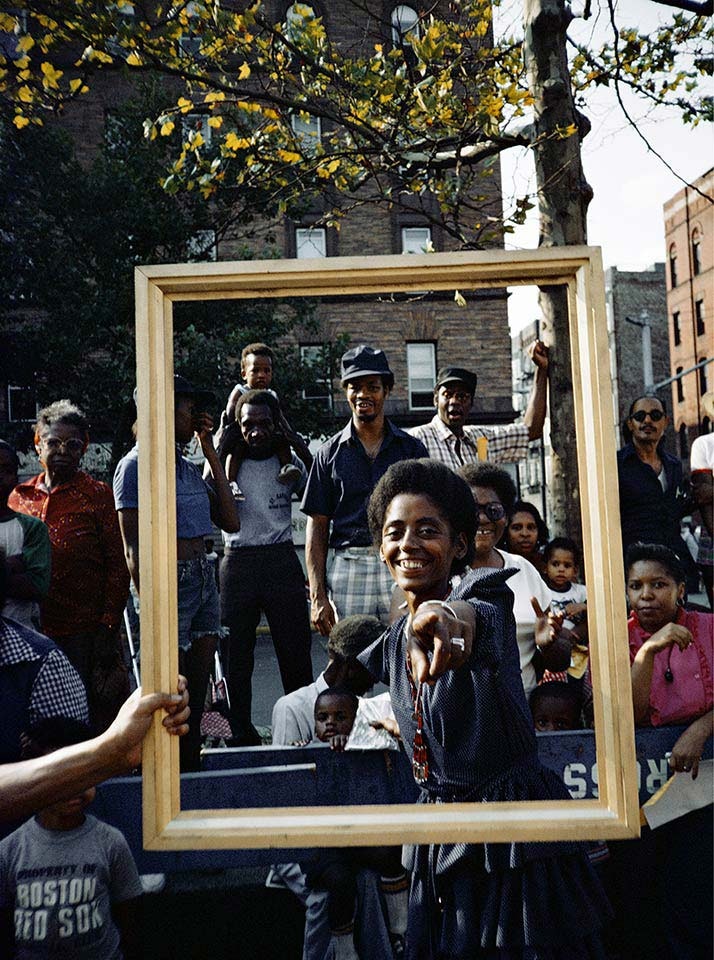

The ‘frame’ staged one of the most prominent figures in feminist theory and critique since the late 1970s. The discourse relating to visual studies, art, and aesthetics, especially though in the field of photography, utilized the notion of the frame as a methodological device for dismantling the supposed objectivity of an image, in particular targeting documentary styles in photography. 3Griselda Pollock and Rozsika Parker, for instance, pursued an art historical perspective in 1987 with the publication of Framing Feminism: Art and the Women’s Movement. Lorraine O’Grady’s performance Art Is … (1983), for instance, took a quite literal approach to the subject, as it revealed it as integral part of the imaging process, while, in retrospect, photography’s Disciplinary Frame – as posited by John Tagg – was the invisible convention of objectivity that needed to be disclosed. 4John Tagg, The Disciplinary Frame. Photographic Truths and the Capture of Meaning (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009). Rather than being a mirror of reality, the photography appeared as a means to construct the very reality of experience. More recently, Kerstin Brandes has pointed out how artists like Carla Williams and Lorna Simpson have expanded the tool since the late 1980s, demonstrating how ‘race’ ties in with the dominant framings prevalent in white male hegemonic societies. 5Kerstin Brandes, Fotografie und “Identität”: Visuelle Repräsentationspolitiken in künstlerischen Arbeiten der 1980er und 1990er Jahre (Berlin: transcript, 2009), 127–150. The frame was an analytical means for acknowledging the context of the image – that is, the specific ways in which it was produced and presented.