Act and Position

Following up on the previous discussion of how Things Are Queer as part of the first entry of this blog series, Duane Michals’ artwork can be interpreted as an appeal to the beholders to resist falling into the trap of essentializing reason. Rather than identifying any certain object as queer, the viewers were invited to explore perception beyond recognition, thus dissolving the narrow framework of expectation. Michals’ critical dismantling of the reception process indeed prevents us from ascribing the attribute ‘queer’ to the responsibility of the Other. It does not preclude to ask about what queer approaches imply or can be about though. What does it mean when it is utilized as a theoretical, political, and activist means? And how is photography as a medium and practice involved in imagining and imaging a queer vision of societies?

At this point, it is worth noting that queer artists making queer art is not a tautological correlation. A profoundly queer artwork does not necessarily require queer authorship, even more as artists assigned a certain queer status may too contribute to hegemonic orders of society. This might sound confusing and it probably is, given that queer explicitly does not serve as another essentialist category of identity marking an inherent feature of any entity. Deriving from Lesbian and Gay Studies, Queer Theory set out to overcome the confines of sexual identities within these discourses. As David Halperin elaborated, queer “demarcates not a positivity but a positionality vis-à-vis the normative – a positionality that is not restricted to lesbians and gay men but is in fact available to anyone who is or who feels marginalized because of his or her sexual practices”.1David Halperin, Saint Foucault. Towards a Gay Hagiography (New York, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995), 62.

As a matter of fact, this is not the only definition. David Getsy for example designed queer as an “adjectival apparatus and performativity”, 2David Getsy, “Ten Queer Theses on Abstraction”, in: Jared Ledesma (ed.), Queer Abstraction (Des Moines: Des Moines Art Center, 2019), 65–75, 65. whereas Eve Kosofsky-Sedgwick proposed that “’queer’ can signify only when attached to the first person.” 3Eve Kosofsky-Sedgwick, “Queer and Now”, in: Eve Kosofsky-Sedgwick, Tendencies (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1993) 1–20, 9, emphasis in original. These propositions don’t need to compete with each other. They rather sum up the various constellations within which “forms of resistance to cultural homogenization [and] counteracting dominant discourses” may be enacted, as Teresa de Lauretis emphasized. 4Teresa De Lauretis, “Queer Theory: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities. An Introduction”, in: differences. A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, No. 3.2 (1991), iii–xviii, iii. The term queer delineates an act as well as an attitude, and as such also relates to a specific temporal and spatial condition. The latter is even more important to consider as queer derives from a specific western language and perspective. “What is queer in Zulu?”, South African artist Zanele Muholi asks. 5Gabbeba Baderoon, “Gender within Gender: Zanele Muholi's Images of Trans Being and Becoming”, in: Feminist Studies, Vol. 37, No. 2 (Summer 2011), 390–416, 392.

The issue of an ever elusive condition of ‘queer’ is well discussed. Attempts to determine a consistent queer program are as frequently undertaken as they have failed. 6Karl Whittington, “Queer”, in: Studies in Iconography, Vol. 33 (2012), 157–168, 158. Albeit failing does not necessarily equal defeat, 7J. Jack Halberstam beautifully advocates for a Queer Art of Failure in: Halberstam, Judith “Jack”, The Queer Art of Failure (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011). a lack of clear definition might weaken queer projects against not overly sympathetic attacks. 8See Rüdiger Schnell, “Queer Theory: Eine Theorie? Beobachtungen eines Mediävisten”, in: Poetica, Vol. 44, No. 1/2 (2012), 1–23. Considering this very inchoate outline of queer theory, it is not a random coincidence that many queer artist choose photography as their medium for making queer art. The correlation can be linked to idiosyncratic features that are inherent to both subject matters: Just like queer theory, the photographic medium resists not only a proper definition of its ‘nature’ and instead instigated a multiplicity of ontologies. It also relies on time and place as well as a deliberate frame in which objects are staged to appear, intentionally taking a distinct perspective and a preference for the particular rather than the universal. This does not mean that photography is an inherently queer medium, or that from a queer angle it is privileged compared to other forms of artistic expression. Such a claim would contradict all of the above. Still, there might be a certain feature of photography that provides a distinct potential for queer endeavors. Fiona McGovern and Daniel Berndt have stressed the significance of the projective apparatus: “By looking at photographs, our gazes align with the perspectives of the artists. We are confronted with the task of positioning ourselves with their point of view.” This becomes an issue specifically with “photographs that deal with subjects challenging hetero-normative and cisgender perspectives and that foreground sexuality”. 9Fiona McGovern & Daniel Berndt, “Public Display of Transgression. Exhibiting Queer Photography”, in: Photoworks Annual Magazine, No. 24 (2017), 172–183, 173.

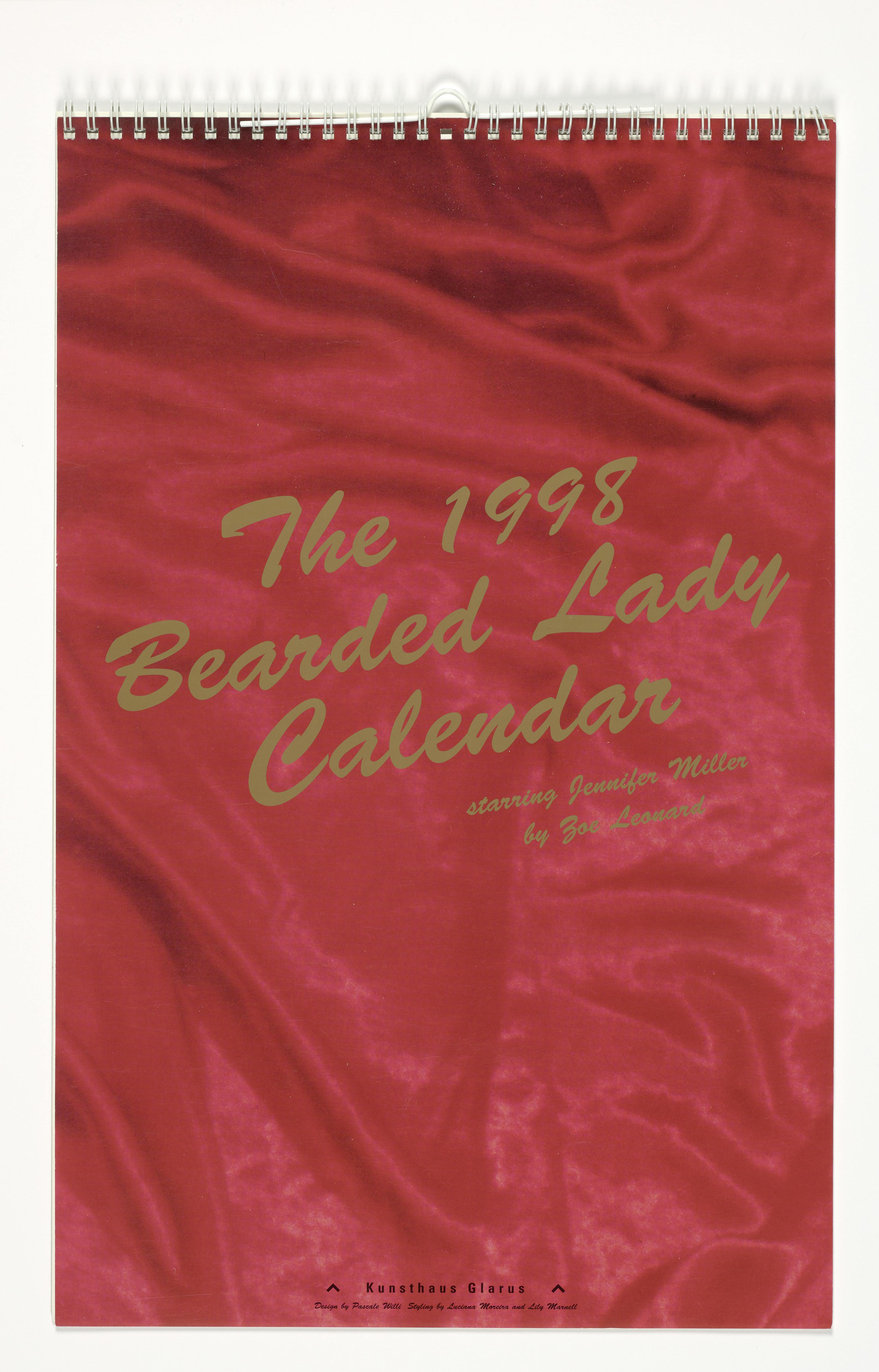

Zoe Leonard, The 1998 Bearded Lady Calendar (cover), 1998, offset print, calendar, 44 x 28 cm, Collection Fotomuseum Winterthur

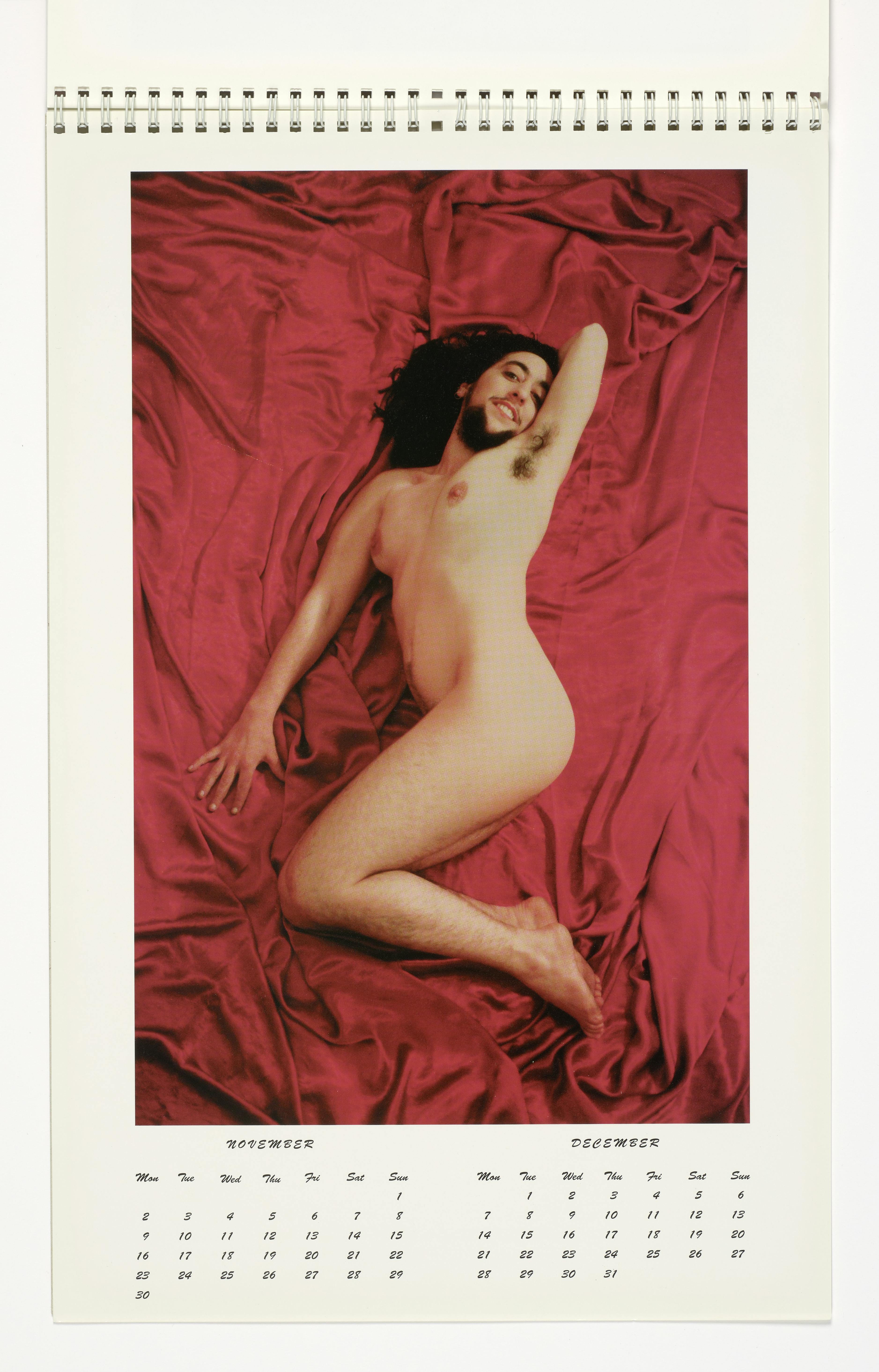

Zoe Leonard, The 1998 Bearded Lady Calendar (cover), 1998, offset print, calendar, 44 x 28 cm, Collection Fotomuseum Winterthur Zoe Leonard, The 1998 Bearded Lady Calendar (November/December), 1998, offset print, calendar, 44 x 28 cm, Collection Fotomuseum Winterthur

Zoe Leonard, The 1998 Bearded Lady Calendar (November/December), 1998, offset print, calendar, 44 x 28 cm, Collection Fotomuseum WinterthurOne such challenge might be found in Zoe Leonard’s The 1998 Bearded Lady Calendar (starring Jennifer Miller by Zoe Leonard), an actual photo-calendar with seven sheets that comprise a cover and a seemingly classical pin-up for every second month of the year. Not so classical at last, as the title already indicates an aberration from the dominant protocols of femininity. The meticulous re-staging of Marilyn Monroe’s famous pin-up for Applied Electronics Supply’s customer giveaway shows Jennifer Miller imitating the pose of her archetype, lounging nude on a lavishly draped, red velvety fabric. Her legs coquettishly bent at the knee, one arm stretched out to the side, the other folded back supporting her head and proudly revealing an armpit with thick dark hair, the model looks straight into the camera with a radiant smile. A smile that is surrounded by a carefully groomed beard.

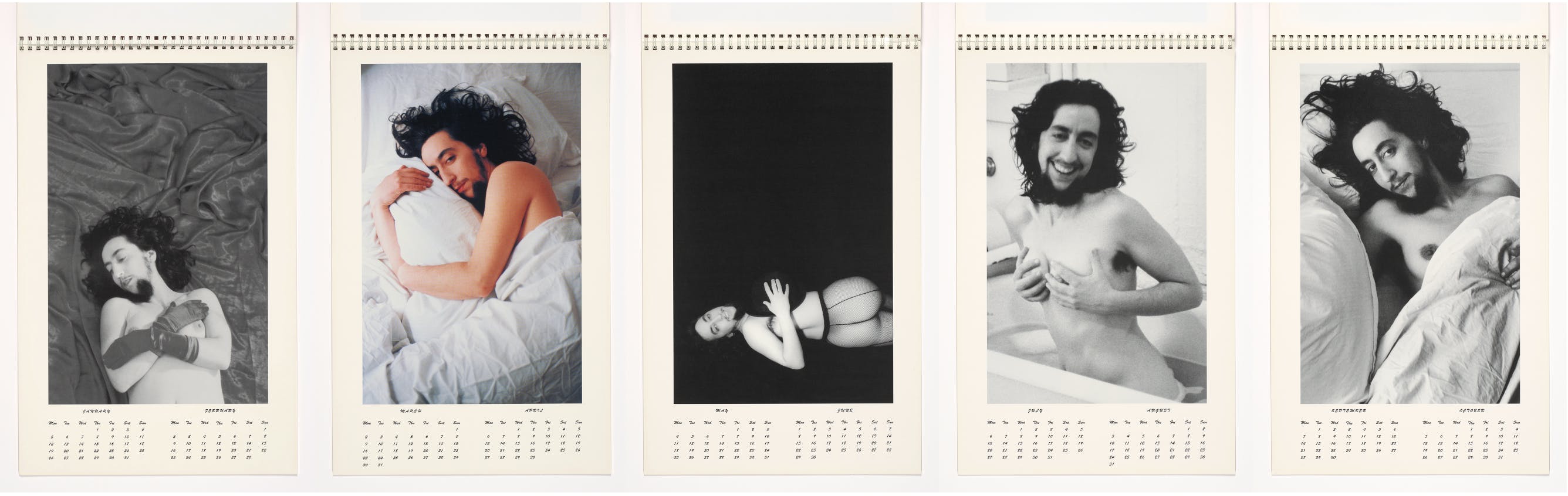

Zoe Leonard, The 1998 Bearded Lady Calendar (January–October), 1998, offset print, calendar, 44 x 28 cm, Collection Fotomuseum Winterthur

Zoe Leonard, The 1998 Bearded Lady Calendar (January–October), 1998, offset print, calendar, 44 x 28 cm, Collection Fotomuseum WinterthurThroughout history, women with beards were stigmatized as freak show attractions or provided the subject of medical examination to explore and document their monstrosity, equally staging a spectacle for the sciences. Treatments came with severe humiliation, poverty, and social abjection. An excess of facial hair turned a person that was supposed to be identified as a woman into a creature that was almost denied humanity at all. This signifier of masculinity fatally attached to the supposedly wrong person violated the established order of two distinct compositions of men, female and male, man and woman – an offense that could neither be tolerated nor remain unsanctioned. From a contemporary perspective the historical Bearded Lady can be declared queer as she didn’t fit one or the other position of the binary.

Staging a model with conflicting signifiers of gender in a pose of ideal femininity, Leonard is not just presenting queer content. The 1998 Bearded Lady Calendar profoundly queers the subject matter. It appropriates and troubles one more ‘technology of gender’ that contributes to the myth of a gender binary and equally charged ideas of beauty: the ordinary pin-up calendar as another instance in male hegemonic cultures to visually objectify women. Leonard is not exposing her subject as freak shows and medical experiments did. Instead she presents her as a precious icon of beauty that is looked at in admiration, subverting the popular template of this male gaze with its own weapons. More than the beauty icon Marilyn Monroe was ever allowed to be, performer, circus director, writer, and professor Jennifer Miller is in charge of her own image. For the viewers it takes effort to resist aligning with Leonard’s affectionate view, to not recognize a beautiful and self-confident human being. The 1998 Bearded Lady Calendar doesn’t erase a cruel history of sexist and deprecatory fashion. The imageless cover page actually gives room for a collective memory of that, only to interrupt and challenge that memory on the remaining sheets with a queer vision that transcends the boundaries of normative femininity and beauty.