On the Invisible (Image and Algorithm)

First we want to specify a point concerning the last sentence of our first post. In his “Postscript on the Societies of Control”, published in French in 1990 (that is, a few years before the launch of the first public web browser), Deleuze opposes the old disciplinary societies as analyzed by Foucault to the present societies of control. He writes:

“The disciplinary societies have two poles: the signature that designates the individual, and the number or administrative numeration that indicates his or her position within a mass. […] In the societies of control, on the other hand, what is important is no longer either a signature or a number, but a code: the code is a password, while on the other hand disciplinary societies are regulated by watchwords (as much from the point of view of integration as from that of resistance). The numerical language of control is made of codes that mark access to information, or reject it. We no longer find ourselves dealing with the mass/individual pair. Individuals have become ‛dividuals,’ and masses, samples, data, markets, or ‛banks.’” 1Gilles Deleuze, “Postscript on the Societies of Control”, October 59 (Winter 1992): 3–7, here 5.

Today, with Big Data as the new ‘oracle’, we need to revise this last sentence: The digital subject is divided in multiple data scattered in numerous data banks, so that the mass/individual pair becomes big data/personal data.

We are now ready to come back to the algorithmic image (and its relation to the data).

The modern programme of the image, the principle of geometric projection, of the world scaled to human dimensions, has worked for about five centuries, until the wide-spread application of digital programming to imaging in the second half of the 20th century. During this period, the convergence of vision and representation has been continuously perfected, so that at the end of the 20th and at the beginning of the 21st century, we make no difference between the way we see the world and the photographic image – Augmented Reality works precisely because of this common reference system of vision and representation, which we have called the photographic paradigm of the image. The modern machine of vision and the modern machine of power have been functioning (and reinforcing each other) at full speed. But in the last decades something has changed deep inside the mechanics of the image and the mechanics of power.

The three revolutions of the image (perspective; photography; digitalization) are a series of paradigm shifts, with the new paradigm superimposing the old, each paradigm being valid in its specific domain. With the photographic revolution, the principle of optical image projection, which has existed since antiquity with the camera obscura, and the principle of linear perspective, which was formalized in the Renaissance, has been supplemented by an opto-chemical principle of capture/fixation. This principle of fixation of vision has then been supplemented by a principle of movement (film), signal processing/transmission (video and digital image). Linear perspective, however, has remained at the heart of the image, from The Ideal City to SimCity.

"All-new SimCity experience." Opening image of a series of five SimCity views (with instructions for prospective SimCity builders) that can be navigated clockwise or anticlockwise.

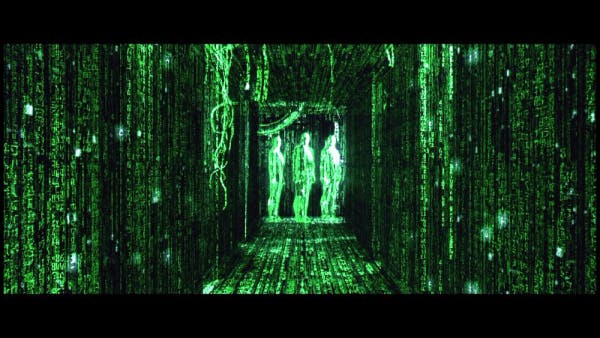

"All-new SimCity experience." Opening image of a series of five SimCity views (with instructions for prospective SimCity builders) that can be navigated clockwise or anticlockwise.And the data cities (or the data world) are often visualized as perspectival cityscapes with binary code texture-mapped on top. Just think of the famous “digital rain” scene in The Matrix, where the illusion of architectural solidity is shattered... only to reveal a solid perspectival construction of zeros and ones!

Screenshot from The Matrix, USA 1999, Andy & Larry Wachowski. (The website from which this still is taken addresses the shattering of another solidity: one of the Wachowski brothers coming out as a transgender woman in 2011.)

Screenshot from The Matrix, USA 1999, Andy & Larry Wachowski. (The website from which this still is taken addresses the shattering of another solidity: one of the Wachowski brothers coming out as a transgender woman in 2011.)But the third revolution, the digital revolution, is not merely about the transformation of images into zeros and ones, into bitstreams and pixels, it is about its algorithmization: compression and decompression protocols such as JPEG or MPEG that reduce storage space/bandwidth and Transmission Control Protocol/Internet Protocols regulating/routing its transfer across digital networks etc. With digitalization, the mathematics underlying the image is no longer merely geometric but increasingly algorithmic: protocols that regulate when/how an image (or image element) is displayed on screen, when/where/how it is being sent to/how it changes if a user clicks on it (an ad for instance) or what is considered a suspicious visual pattern and how it is detected etc. With navigable image databases, or rather databases that are navigable as images, such as Google Street View, what the on-screen image actually displays is subject to database updates, connection speed, screen resolution and navigational options provided by the software and the real-time correlation with a given user query or user location. This dynamic relation between data and data is the foundation of the algorithmic paradigm of the image. No longer a means or a medium of human communication, the image today is a tool for human-machine and machine-machine communication, and its new syntax is that of algorithms or finite sets of instructions in which fixed values are replaced by variables 2See in this context Lev Manovich’s argument of “the key effect of the computer revolution” being “the substitution of every constant by a variable” (234) in The Language of New Media (Cambridge/MA: MIT Press, 2001).. Algorithms are encoded into programs, using computer languages, and are executed when running the program. An algorithmic image, then, is de facto a (computer) program.

But as we argued above, this paradigm shift (from geometry to algorithm) is actually a paradigm superimposition, with the old paradigm (projection) being embedded into the new paradigm (processing). This superimposition is made possible by the fact that geometric perspective itself is a kind of algorithm: a finite series of instructions for the construction (creating) and deconstruction (viewing) of images, an algorithm that is based on, and generates, the (visual) commensurability of image and world. The real revolution is then cybernetic: if the old algorithm of projection runs once and for all, the new, computational algorithms run in a real-time feedback loop with each action of the viewer functioning as a new input. If the progressive convergence of vision and representation has made possible the instrumentalization of the gaze since the 15th century, its algorithmization has made of the image the center of multiple operations: an ‛operative image’ 3See the introduction to the online cluster, THE OPERATIVE IMAGE, curated by Ingrid Hoelzl, which proposes five contributions that apply the term – originally coined by Harun Farocki in 2004 in the context of automated warfare – to computer vision, neuronavigation, cyberforensics, and the computer interface.

. Paradoxically, the changes brought to the image by the ‘algorithmic turn’ 4William Uricchio, “The Algorithmic Turn: Photosynth, Augmented Reality and the Changing Implications of the Image”, Visual Studies 26, 1 (2011), 25–35. are not so much on the level of what we see, but on the level of what we do NOT see; these operations taking place behind the user interface, within the processor of the computer, within digital networks, and, most importantly, in data centers housing the world’s data – from corporate databases to private emails.

Night falls over our Lenoir, North Carolina data center, from Official Google Blog, “Google’s data centers: an inside look”, October 2012.

Night falls over our Lenoir, North Carolina data center, from Official Google Blog, “Google’s data centers: an inside look”, October 2012.Here, the visible side of what we could call the new ideal city (and perhaps the ultimate project of postmodernity): the data city. Cloud computing does not take place in the ether but on the ground; it takes up space, it is made of wires, metals etc., and it uses tons of electricity for cooling. The data city is no longer tied to the physical city; on the contrary, data centers tend to be in remote areas. Google’s North Carolina data center, for instance, is located in the small town of Lenoir, which currently has, according to Wikipedia, 18,228 inhabitants. The blog announces Street Views of the exterior of the data center and of its interior, including the server floor. But this campaign should not fool us; when we actually embark on a virtual tour of the server floor, starting in the corridor, clicking on the navigational arrows does take us three steps closer to the actual server racks, but only close enough to see (and eventually zoom in on) a human being guarding the racks, and a tiny robot. Likewise, Google’s website ‛Where the Internet lives’, presenting its data centers (‛tech, people, places’), features ‛beautiful photographs’. But where the Internet really lives is not shown on these images. On this invisible (hidden) materiality of the Internet see also John Bridle’s inspiring lecture Big Data? No thanks linking it to the history of computing, nuclear warfare and big data.

This hidden operativity of the image is built upon an understanding – and exploitation – of the world as a database. With Google Street View or Google Earth, the access to the world is the access – through the image – to a networked database operated by the user whose very operations feed back into the database. These pretended global image databases (Google’s Amazon campaign only glossing over the fact that large parts of the globe, in particular of Africa, are not in it) prove that today, global control is strongly linked with imaging and image allocation. The operativity of the image is two-way: when we operate an image in an online application, the image is actually operating us (tracking our trajectory in Google Street View; appearing as ‛personalized’ ads in Google). This is the new programme of the image: that of invisibility and control, a control typically masked behind ‛service’, ‛usability’, ‛security’ etc.

What we are positing here is that the programme of the algorithmic image (its hidden operativity) is a programme of obfuscation. While illuminated manuscripts of the Middle Age explicated the Holy Scriptures by visual means (for the illiterate), our illuminated screens hide the script of control (for the programming illiterate). An interesting example of this new paradigm of the visible/invisible image can be found in the book Invisible: Covert Operations and Classified Landscapes5Trevor Paglen, Invisible: Covert Operations and Classified Landscapes (New York: Aperture, 2010). by the American artist Trevor Paglen (and a previous blogger on Still Searching). In his series Limit Telephotography of which this particular image is part of, Paglen employs high-end optical systems to photograph top-secret military sites; sites which do not exist on the map and whose existence and cost are not publicly disclosed.

Trevor Paglen, The Tonopah Test Range, distance = ~17 miles.

Trevor Paglen, The Tonopah Test Range, distance = ~17 miles.This image claims to show the invisible: a military base that neither exists on the map, nor in the official military budget of the US. Actually, the image doesn’t show much; what it shows – vague shapes of a building complex and unidentifiable objects in the foreground – is the limits of vision, the border of the visible/invisible. Yet its caption tells the invisible: the name of the building, its location, and the distance from which it has been photographed and, on his website, Paglen gives a detailed account of its history as a base for stealth fighter planes (planes designed to be invisible to radar, visible light, radio frequency, and audio), but cannot reveal anything about its current military function, the nature of which is "obscure".

Compared to The Ideal City, this image exemplifies the new mechanics of the image and of power that we mentioned in the beginning of this blog post: The former is a perfect image of a perfectly ordered world, where everything is exposed in plain sight (even if the popular buildings in the background are partly occluded). The latter is a blurry image of a secret base where all parts of the image are equally underexposed. Hence, we have moved from a regime of the visible and enlightenment to a regime of the invisible and of obfuscation. Of course the story of the two images is different and Paglen’s photo is not a commissioned work for a prince of our times (nowadays artists rarely work on commission anyway). But how tempting to imagine a large size print of The Tonopah Test Range photograph hanging on the wall of CEO Sundar Pichai’s personal office at the Googleplex in Mountain View – as a symbol of both secrecy and transparency: secrecy of its algorithms and of its data centers (heavily guarded like military bases); transparency of user data... to Google and to the NSA?