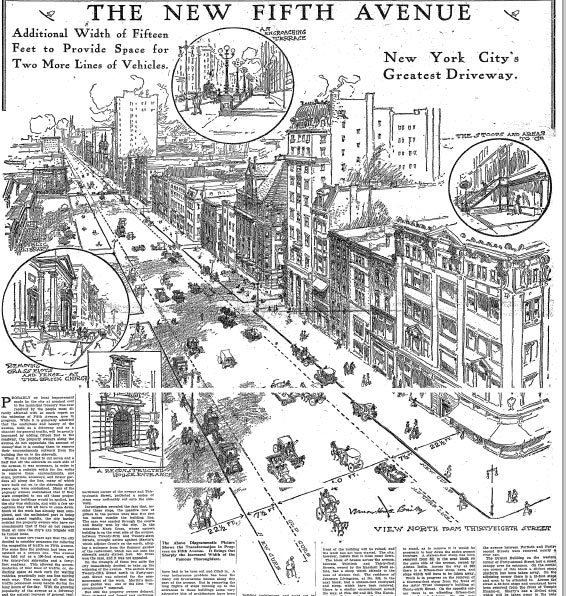

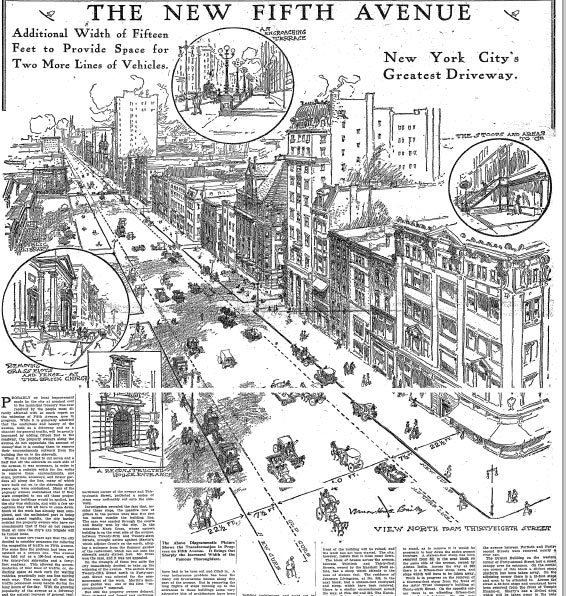

Strand left us few hints of what he thought about skyscrapers at this time, but during 1917-18 he began writing poems, one of which he entitled “The Avenue.” The narrator, perched above the “wet and mudded” street “with the meltings of first snow,” invoked a melancholy spectacle: “The heavy massed forms/ Of tall buildings tower/ Into the grey nothingness,/ Like giant specters,/ Whose myriad eyes,/ With sinister light/ Gleam dimly yellow/ through the thick damp./ And the people swarm/ Ant-like,/ And the machines/ Stream endlessly by.” This sunny photograph of Fifth Avenue is, of course, not the wintry, twilight scene Strand invokes (he tellingly does not attempt the nocturnal photographs that intermittently occupied Alfred Stieglitz), but the mood of ominous towers glaring down on worker ants says much about the dehumanization of big buildings (and, I would argue, the rapacious magnates who built them).