Unlearning Imperial Rights to Take (Photographs)

The millions, whose photographs are taken, are not referred to in any meaningful way in the histories and theories of photography. Beaumont Newhall’s The History of Photography is a paradigmatic example. His fourth chapter, for example, is titled “Portraits for the Million.” 1Beaumont Newhall, The History of Photography: From 1839 to the Present (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 1949), 7. The seven-digit figure is evoked here to celebrate the medium, not the power of the people, whose attempts to get together and unionize in large numbers was often crushed rather than praised. From a very early stage, it was assumed that the people photographed, not the spectators, are to provide the resources and the cheap or free labor for this large-scale photographic enterprise. The many involved in photography were considered extras, secondary actors or raw material, while the work of some photographers was singled out to constitute the spine of the history of photography.

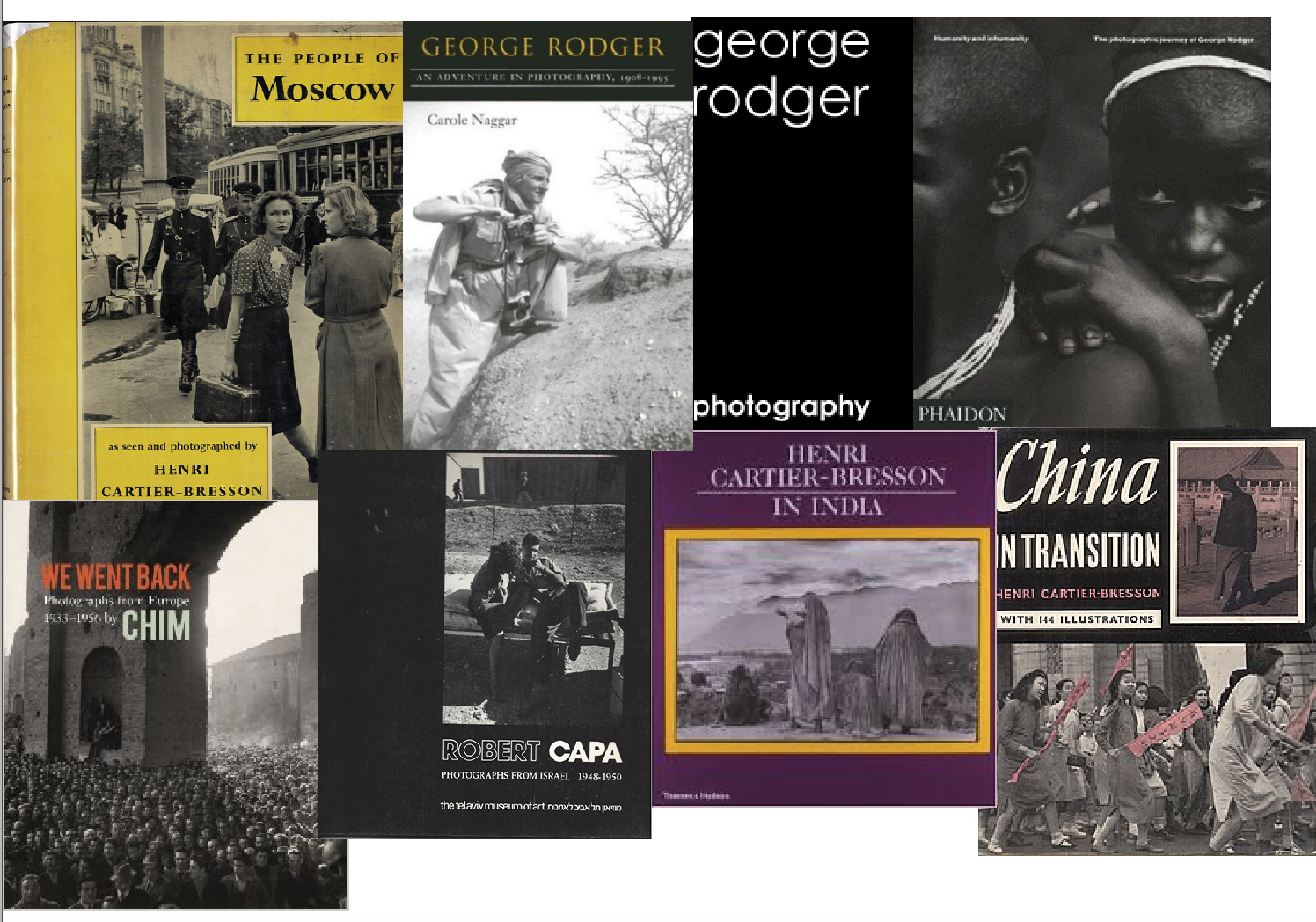

Though they were not the big imperial entrepreneurs or profit makers, photographers enjoyed imperial rights that provided them with the license “to go almost anywhere they wanted.” As Magnum’s official history states,

“In those days a photographer had a significant advantage: large areas of the world had hardly ever seen a photographer. They could choose to go almost anywhere they wanted, as Rodger [George] pointed out, because in the early days one could ‘take pictures of just about anything and magazines were clamoring for it. . . .’

Magnum’s first move was to divide the world, rather loosely, into flexible areas of coverage, with Chim in Europe, Cartier-Bresson in India and the Far East, Rodger in Africa, and Capa at large and replacing Bill Vandivert (an American who had helped found Magnum but soon dropped out) in the USA.”

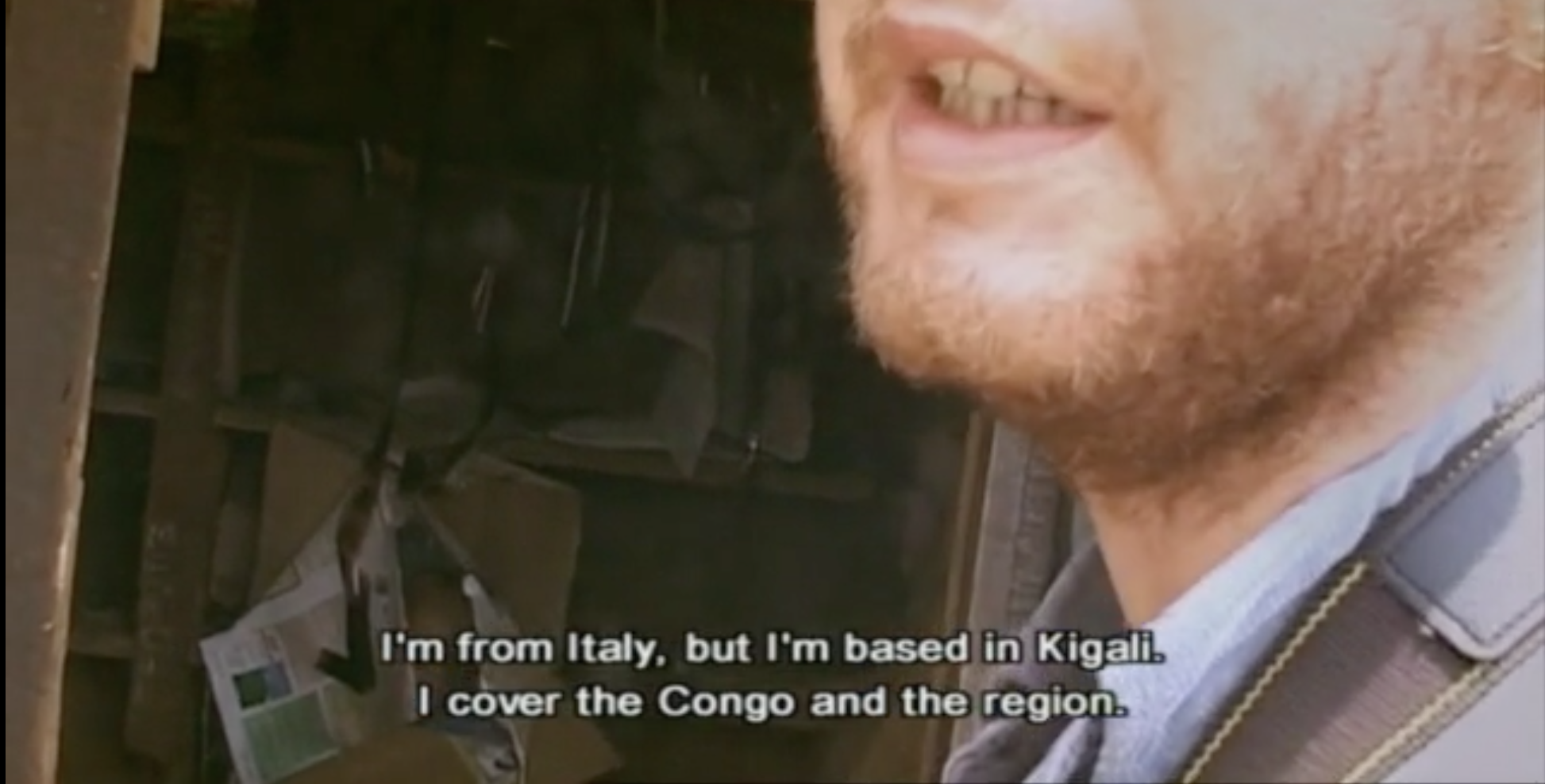

Given that free or cheap labor is extracted from others, photographers act as middlepersons between those photographed—the objects of their craft—and other imperial agents. It is in exchange for this that they could benefit from the imperial domination of photographic markets and could claim single authorship of their photographs, even though their production involved many other people.

Accorded the right to deprive other participants of their share in the photograph, photographers did not necessarily enrich themselves, but they did enable large corporations, collections, and institutions to benefit from the free labor and from the presence of innumerable photographed persons who fueled the industry.

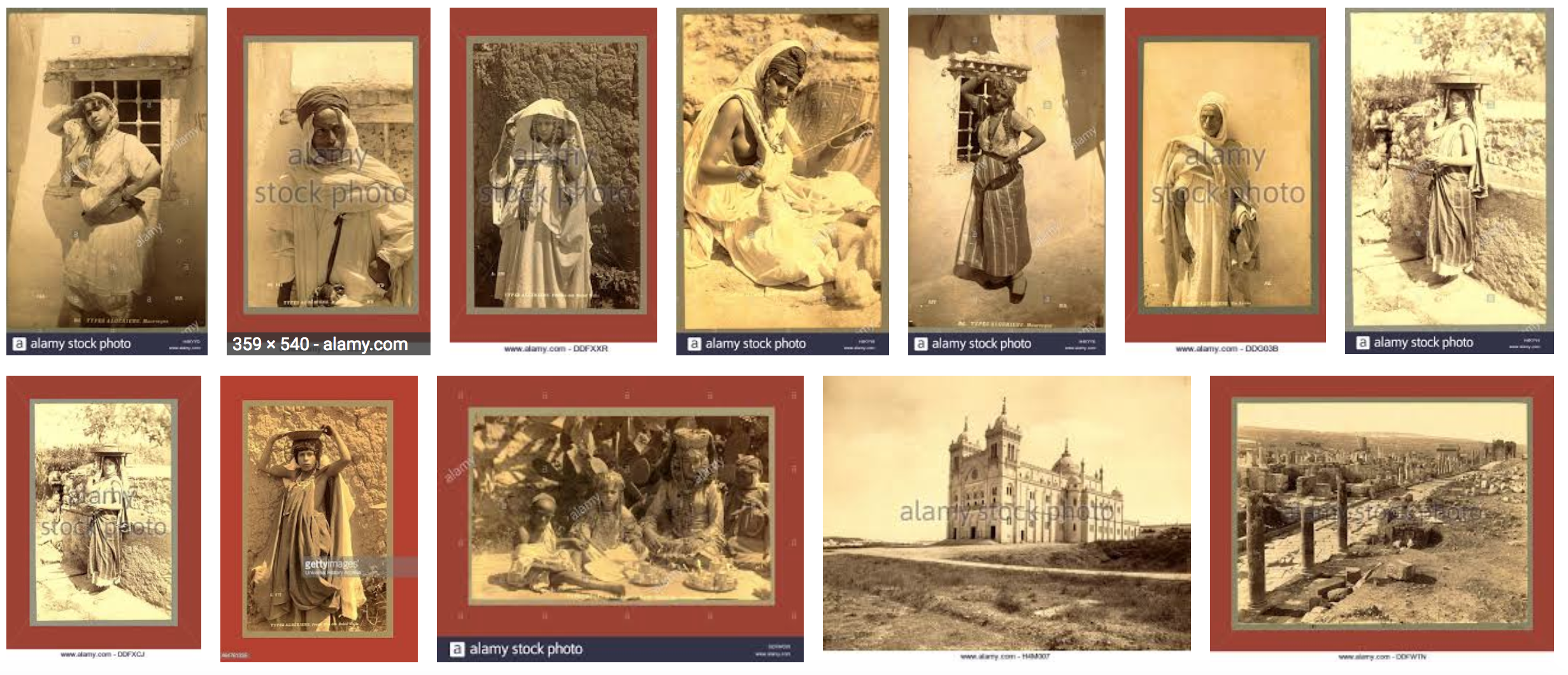

Not surprisingly, such rights that are not inscribed in any community could be revoked as easily as they were given, and with no remorse, and photographers could always be dispensed with if no longer needed—as photographers experience with the mass appropriation of photography by image bank corporations that claim exclusive ownership of “their” work: this can be seen here in the screenshot of a random Google search with the categories “types / Algeria”—what was once the property of the Neurdein brothers is now distributed as the property of Alamy image bank. 2One among many examples of such a monopoly is Algeria: “Today the monopoly of French and European photographers recording Algeria appears sustained. . . . Photographers such as A. Abbas, Raymond Depardon and Nicolas Tikhomiroff are the biggest names when searching for photography of Algeria,” Leyla Reynolds, “Agency & Exoticism: Algerian photography in the 1890s,” Autograph Media.

As cultural agents, photographers didn’t enjoy the same privileges as those imperial agents who crafted and distributed imperial rights the world over. In exchange for their privileges and symbolic capital, photographers were expected to conceal the exploitative meaning of the photographic encounter—an encounter in which those stripped of their rights in their own communities had to become free resources for growing markets, skilled artists and artisans, fields of knowledge, and disciplines. The dominant discourse of human rights, however, ignores these rights when referring to photography, and the discourse of photography is mostly limited to describing how violations of rights are represented in photographs and can be advocated through them (as in “photographs of human rights”) or to discussing rights pertaining to the “end product” of photography—i.e., the photograph—including rights of ownership and authorship (copyrights) and rights of protection, dissemination, and management. In both ways, such an approach excludes in advance the recognition of the participation of different parties in the photographic event. The right to take photographs was imposed from the start as given, unlimited and inalienable, often against the will of others.

Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography, Slought, Philadelphia, from: https://slought.org/resources/collaboration_a_potential_history

Collaboration: A Potential History of Photography, Slought, Philadelphia, from: https://slought.org/resources/collaboration_a_potential_historyOccasionally, as explored in the exhibition Collaboration, photographers reconsider their form of involvement with others and seek alternative ways to engage with other participants in the photographic event. Constraints that are occasionally imposed upon this right by officials and representatives of imperial powers—the army, police, or the state—helped to further dissociate the common ground between photographers and those photographed and shape the persona of the photographer as if this persona is not part of these powers and not working under the aegis and protection of the violence they exercise, but is rather an agent of criticism and opposition, documenting the wrongs perpetrated by these powers. Photographers, like artists, acquire, as part of their professional habitus, the right to relate to others’ worlds as raw material, or in today’s language as “references,” as materials used for study, admiration, or appropriation. Hence, they often resist the constraints imposed on their capacity to exercise their profession by the state and its subsidiaries and inhabit the position of a sort of “freedom fighter,” struggling to keep their right to free movement and speech and remove obstacles put in place by authorities on their way to pursuing their mission. This however, is usually done without acknowledging, let alone problematizing, the inherited imperial privileges that make the photographer’s position possible.