The Creased Portrait of a Lady

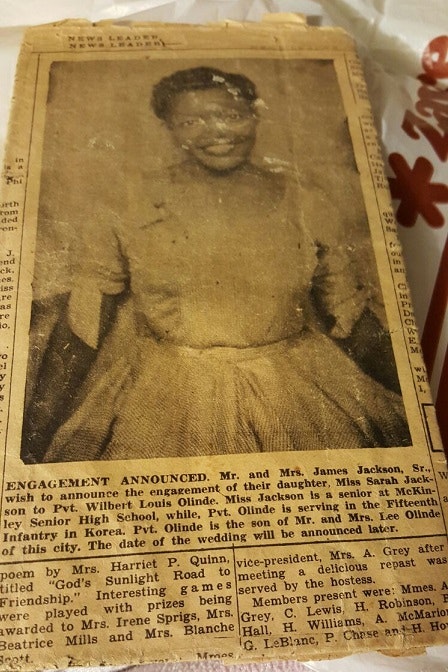

Someone smiled decades ago and now she stops you in your tracks. Early in 1953 Sarah Jackson posed for a studio photographer in Baton Rouge, Louisiana. She was 16 years old, a high school senior with six siblings. On Mississippi Street her family ran “Jackson Groceries.” Because Sarah worked so hard in the store, her father called her “Jim.” She was engaged to be married to a man named Wilbert Olinde. On this particular day she was wearing a bright dress with thin stripes and loopy sleeves. Maybe the photographer asked her to hold up her dress, just to make it fold out almost all the way across the picture.

Sarah Jackson passed away in 2013. Two years later, I started writing a biography of her son, born in 1955. His name is Wilbert Olinde, Jr. He was one of the first African American basketball professionals to play in Germany. He holds a B.A. from UCLA and a postgraduate degree in economics from the University of Goettingen and now works as a life coach in Hamburg, Germany. Wilbert Olinde, Jr. showed me this photograph and he said it was ok if I talked about it here.

The creases struck me. Diagonal ones in the top half. A major crease roughly separating the highly creased lower third of the photograph from the slightly less damaged upper two thirds. The creases asked questions. Like: How could anyone damage this photograph?

You could start by saying that the picture moved around a lot. It was part of the Great African American Migration from the South. In 1956, leaving poverty and institutionalized racism behind, Sarah, Wilbert Sr., Wilbert Jr., and this photograph migrated from Louisiana to Southern California. They found a place in San Diego. Moved in. Found another place. Moved again. Wilbert Sr. worked construction. Sarah was a nurse. They had another child, a girl. Sarah enrolled at San Diego State. Locked herself in the bathroom when she had to study. Got a college degree. Became a teacher, then a principal. When crime soared in their neighborhood, they moved again, to the suburbs. They divorced. Another move: Sarah spent two years in Sacramento working for California’s school administration. What a career. After two years she missed teaching and moved again. Back to San Diego. Back to another position as principal. She had a new partner who called her “Foxy.” Retired. Moved again, to Las Vegas, because she thought the climate would suit her. In Las Vegas, though, Sarah hardly ever left the house. She suffered from Parkinson’s and beginning dementia. Finally her daughter took charge and organized the next move. Back to San Diego. A nursing home.

At this point, in 2009, Sarah’s daughter found the 1953 portrait in a drawer of her mother’s bed. And because Sarah’s two children divided up the pictures their mother had crammed into that drawer and because Sarah’s son had moved to Germany, the creased picture ended up in one of Wilbert Olinde Jr.’s personal photo albums.

Sarah’s – and the portrait’s – relocations can’t explain every crease. There were definitely pictures she paid more attention to than this one. On a snapshot of the family’s 1960s San Diego living room, you can see a photograph on a small table right next to the couch they kept covered in plastic. Protected by a frame, the picture shows Sarah Jackson on the day of her high school graduation. And there’s another completely creaseless portrait in her son’s album: a shot of Sarah Jackson, college graduate in cap and gown. Maybe she only cherished photos documenting achievements. Maybe she didn’t feel enough love for a young woman who happened to be pretty, gracious and optimistic, not even if that young woman was herself.

Her former husband might have agreed. I talked to Wilbert Louis Olinde Sr. shortly before he passed away. They’d been friends, close friends, long after the divorce, but he did sound distanced when he talked about Sarah’s life and the diseases that had ended it. She’d wanted too much, he said. She’d been too ambitious for her own good. Did that make sense? I thought so. Maybe I fell for Wilbert Sr.’s interpretation because I was working on a biography, by definition a narrative of a self, and because I love vernacular portraits for the complicated selves they present. So I ignored context and outside pressures and also started to believe that it was all about self: Sarah Jackson from Baton Rouge had pushed too hard and paid the price. The creased picture seemed to furnish proof.

Then I realized that wasn’t true. In the spring of 1953, to announce the engagement, Sarah’s portrait had appeared in the News Leader, Baton Rouge’s African American newspaper. I don’t have the entire page the photograph was printed on. Just a picture of the picture, the caption, and a bit of unrelated text underneath. But everything on that part of the paper’s page testifies to a community’s enormous desire for respect. The picture itself, of course. The announcement by the Jacksons. And that part of some random article someone cut out along with the picture, a piece that talks about some local society’s meeting and a poem by Mrs. Harriet P. Quinn and prizes awarded and a “delicious repast” served. Just these few lines make you grasp how important and how hard it must have been for African Americans to hold on to their dignity in the Jim Crow Era – and how different Sarah’s photograph might look today if justice had ruled in the South.

Because you really need to ask a few counterfactual questions here. What if there’d been no segregation to drive Sarah away? What if that violent racist system had not shaped Louisiana? What would have happened to her and her engagement picture, if she’d attended the best university in Baton Rouge (Louisiana State, open to white students only) instead of studying for two semesters at underfunded Southern University up in Scotlandville? What if her husband had made decent wages? What if there’d been full equality in all areas of life? Wouldn’t she have stayed in town, if only to be close to her parents and siblings? Wouldn’t she have become a teacher, an administrator, a principal in Louisiana? Wouldn’t she have aged in the center of a big, vibrant family? Wouldn’t she have cherished that 1953 picture as an icon of how it had all begun? Living a much less stressful life in a much tighter community, she might still be around today to talk about that dress and its loopy sleeves and the tall funny man that she married. (He’d said he’d give her the moon if only someone would sell it to him.)

Instead Jim Crow turned her into this hyperflexible migrant. An awe-inspiring figure to any historian lucky enough to portray her. But the pressure must have been intense. Yes, she was ambitious. Overly ambitious? In her time and her context it was the only way to achieve anything that was commensurate with her talents. (It does make sense to echo The Great Gatsby at this point.) So she worked and studied and moved and changed and worked harder, studied, taught, moved again, changed again, her boat against the current, and ignored that ancient, though, to her, probably useless picture of a carefree young lady, a photograph which also transformed and got damaged. You might say this is all speculative. You might say it’s really none of my business. Well, maybe. Look at the creases and see for yourself.