Survival Programmes: An Interlude on Varieties of Documentary

In my next post I will pick up the thread of neo-Brechtian practice, specifically looking at questions of production and skill in photography. However, here I want to look at some forms of critical or radical documentary that have been largely passed over in critical writing. It seems an apposite point to do so; in the last two weeks I’ve read two post-graduate studies on Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen’s work and been asked to referee an article on Half Moon and Camerawork for an academic journal. This material is receiving renewed attention. One central problem with the ‘neo-Brechtian’ line, which I discussed in my last post, is that the avant-garde sensibility dogmatically claimed the mantle of ‘revolutionary’ for its own favoured works, whereas everything else was said to be ‘retrograde’, ‘reformist’ or just plain ‘boring’. Claire Johnstone cited Abortion (1971) made by the US feminist collective Our Bodies Ourselves as an example of a retrograde film; while approved of by many socialists and feminists due to its explicit arguments, Johnstone believed, its narrative characteristics made it a conservative form. Colin MacCabe notoriously equated The Grapes of Wrath and Toad of Toad Hall as comparable examples of the ‘classic realist text’.

It was never apparent to me why documentary was perceived as a monolithic mode or one incapable of renovation. I’m not claiming that the critique of documentary as an outsiders view of the poor, a downward and pitying gaze, was unnecessary. We needed to work through the criticism of the documentary mode, to rethink attitudes and entrenched ways of working. While Allan Sekula and Martha Rosler are often mobilised as critics of documentary, it is often overlooked that both called for the reinvention or expansion of the mode. Their work has been an exemplary meeting point for versions of realism and modernism, which Fredric Jameson advocated in 1977.1Fredric Jameson, “Reflections in Conclusion”, in Aesthetics and Politics (New Left Books, 1977), 196–213. My point is that there is more to documentary photography than the politics of victim mongering and the practice is important for bringing into visibility social class and the politics associated with it. Ariella Azoulay is surely right that photography is a performative practice in which the triad camera, photographer and subject bring into being an image that could only exist in that conjuncture.2Ariella Azoulay, The Civil Contract of Photography (The MIT Press, 2008). The documentary image is not a capture of a profilmic event, or only simply that, but a perlocutionary event. It plays an important role in producing, or cementing an image of class. Similarly, my attempt to think about photography using the ideas of the Bakhtin School (1990) suggested that all photographs are dialogic in form and that the idea of the closed text or the closed image was a misconceived critique of the realist mode. If all forms are dialogic, as Bakhtin suggests, then the answering voice of the depicted subject must also shape the image. Documentary is an open and flexible practice, probably more so than the controlled studio picture. For instance the sequencing of the photo-book or photo-essay provide a complex and multi-layered platform for meaning and reflexion. What is more, as opposed to some other image practices, it is likely to be a much more productive site for critical intervention, precisely because of its ubiquitous political presence across media. This post sets out from this constitutive politics of the visible as the basis for intellectual struggle elaborated in my first one.

Despite the rhetoric of a ‘trickledown effect’ or thinking on economic convergence in which poorer national economies would, through market mechanisms, gradually achieve prosperity, all indications suggest that poverty has increased during the era of neoliberal governance. This applies to both increasing disparities between the rich and the poor and to the increase in absolute poverty on national and international scales. If we remove China from the equation the situation looks even direr. Convergence is an ideological fantasy of neoliberalism, which actually needs a spatial division of labour at odds with that fictive meeting. Yet, during the same period, the images of poverty and the working class have become increasingly absent from the mainstream media. Of course, there have been honourable exceptions, but attitudes towards documentary have played no small part in producing this situation and generating a socio-political consensus. The historian Eric Hobsbawm stated that one of the central political problems of the last thirty years has been that the rich ceased to be afraid of the poor. They have governed accordingly. As a British saying goes, ‘out of sight, out of mind’. Cultural practitioners as different as Brecht, Augusto Boal, Rainer Werner Fassbinder and Jeff Wall have understood that a principle component of realism is the bringing of new characters into visibility.

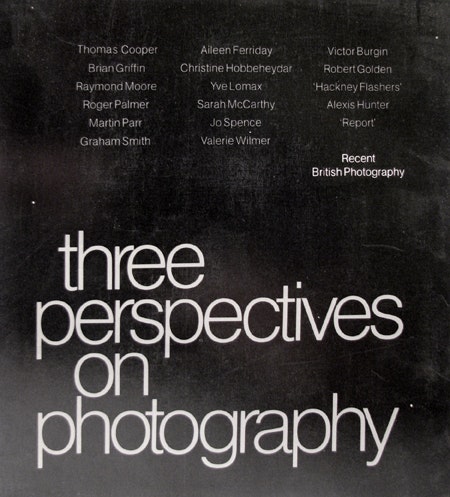

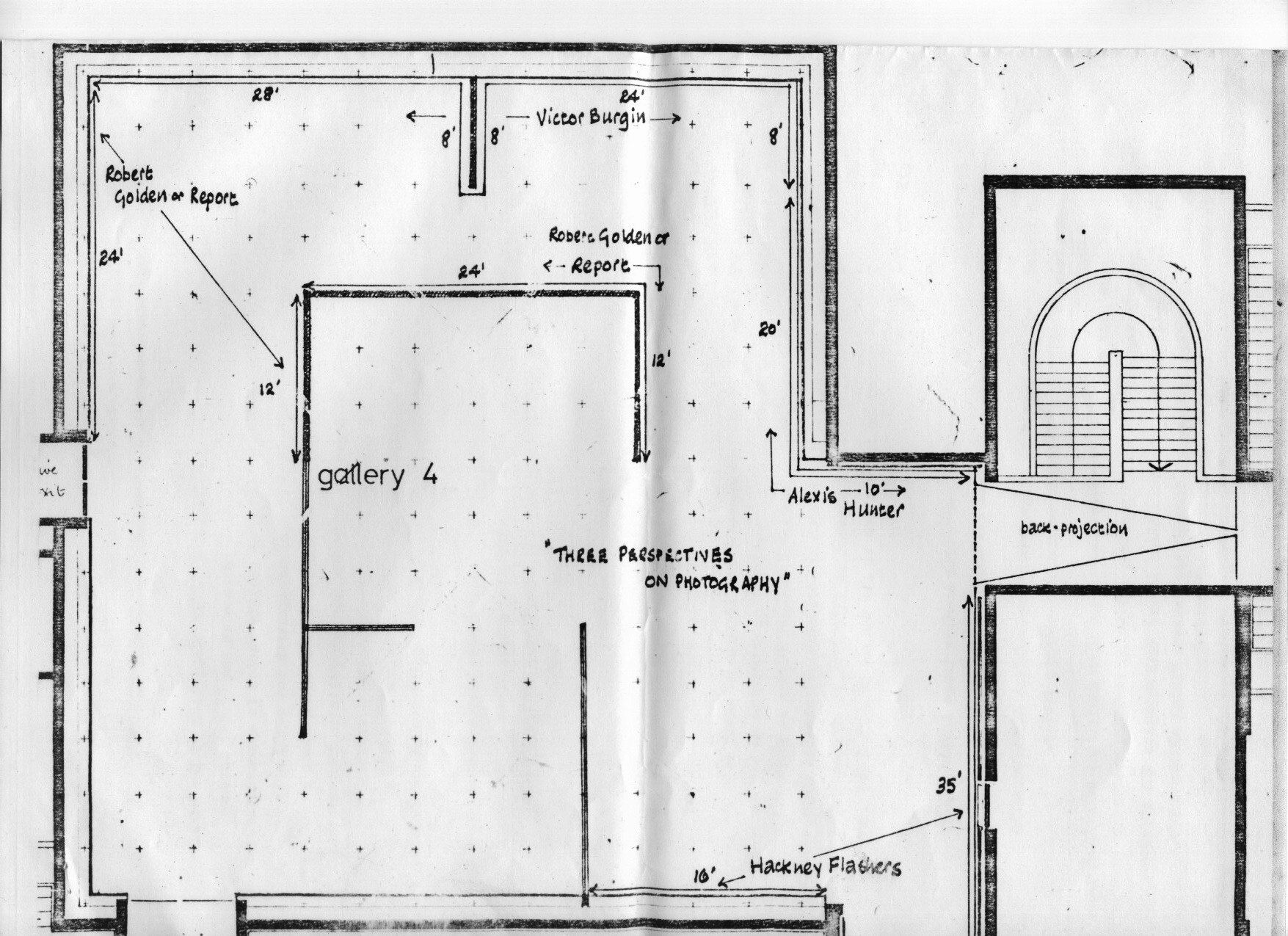

The documentary work of the 1970s was diverse and I want to draw attention to some overlooked practices as an impetus for imagining visibility of these issues in our own time. I wish I had the scope to engage in sustained interpretations of image sequences, but all I can do here is emphasise the range of approaches and indicate the scope of investigative work that still needs to be done. During the period, critical documentary ranged from traditional studies of working lives to highly experimental works. The exhibition Three Perspectives on Photography (Hayward Gallery, London, 1979) is indicative of the variety of photography at the time. This exhibition was divided into three parts, each devised by a particular selector: Paul Hill organised ‘Photographic Truth, Metaphor and Individual Expression’, showcasing black-and-white fine prints; Angela Kelly put together ‘Feminism and Photography’, which included diverse works from traditional documentary images of women’s lives (Christine Hobbeheydar and Valerie Wilmer); portraits by Aileen Ferriday; through to the staged narratives of Yve Lomax and Sarah McCarthy. John Tagg presented ‘A Socialist Perspective on Photographic Practice’ with works by Victor Burgin, The Hackney Flashers, Robert Golden, Alexis Hunter and Report/International Freelance Library (IFL). It is worth noting that almost all of those photographers included in the feminist section and the socialist one could easily have been interchanged.

I’ll return to socialist feminism in my final post. The point I want to make is that in his short text to the catalogue, Tagg argued that photography could only be called socialist if it contributed to the “construction of a new politics of truth”3John Tagg, “A Socialist Perspective on Photographic Practice”, in Three Perspectives on Photography: Exhibition Catalogue, Hayward Gallery, London (Arts Council of Great Britain, 1979).. Yet his selection ranged from Burgin and Hunter at one end to Golden and Report/IFL at the other, with The Hackney Flashers somewhere in the middle.

Much the same could be said about Photography Workshop’s influential volume Photography/Politics: One (1979), which I mentioned in my first post. This book was important in drawing together new work on photography and politics; the focus was almost exclusively on documentary. The third section: ‘Left Photography Today’ includes the work of the Hackney Flashers Collective and their important exhibitions: Women and Work in Hackney (1975) and Who’s Holding the Baby (1978). There is an interview with the Film and Poster Collective, which made works to support political campaigns. Interestingly, Nick Hedges presents a critical assessment of his own work for the homelessness charity shelter. Also included are montage examples of anti-fascist propaganda for Campaign Against Racism and Fascism (CARF); posters for Socialist Worker, the weekly paper of a Trotskyist group, by Golden. There were statements by John Berger and Jean Mohr and an essay by Trisha Ziff on her experience working as a photographer for a Labour municipal council. Documentary in Photography/Politics: One isn’t singular or cohesive; it ranges from the humanist emphasis of Berger and Mohr to the activism of Golden and critiques of victim imagery (Hedges, and Sekula’s essay “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary”4Allan Sekula, “Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary”, Photography/Politics: One, ed. Terry Dennett, Jo Spence, Sylvia Gohl and David Evans (London Photography Workshop, 1979), 171–85.). The cluster of intellectuals and photographers involved were far from naïve about the mode in which they were working, but documentary remained, in some expanded or reinvented form, the vehicle for left-wing politics, capable of both exposing conditions of oppression and exploitation and providing a tool for mass cultural work in a second-wave worker photography.

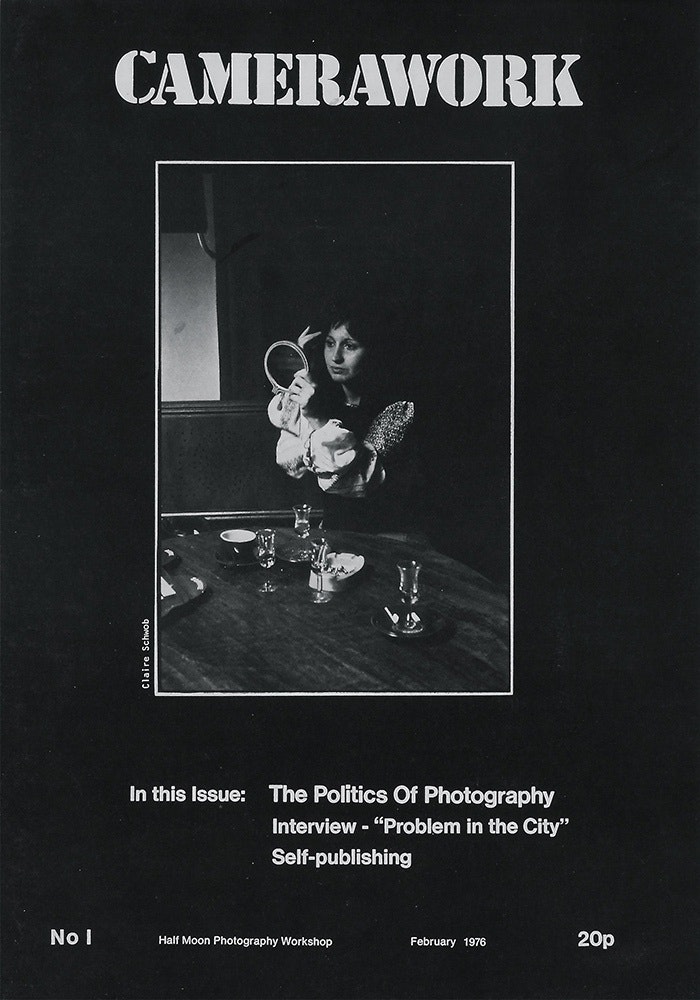

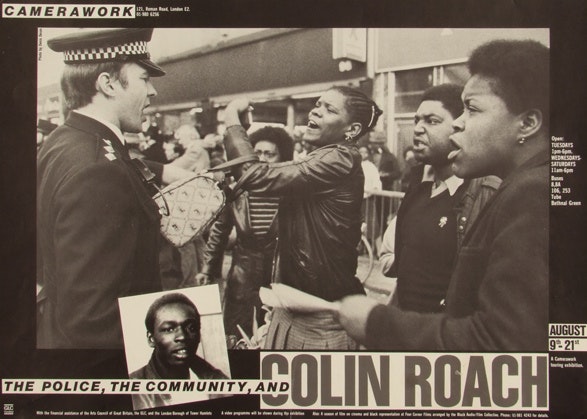

What is more, the period in question saw the emergence of a network of documentary institutions. I mention only some of them here. In 1972 the Arts Council established its photography panel, which along with the Greater London Council (GLC) was the source of much funding for a range of initiatives. In 1976 the first position of local community worker in photography was established to facilitate the use of the medium by individuals and local groups and before long a network of these community action projects in film, photography and poster production were operating from London to Saltley to Liverpool, all providing skills and equipment for acts of self-representation of the dispossessed and marginalised. An example is Bootle: A Pictorial Study of the Dockland Community, in which “the pictures were taken by residents – from kids to pensioners – in our area”.5Bootle: A Pictorial Study of the Dockland Community, A Community Arts Project in Bootle (Arts and Action, 1978). As late as 1986, one publication listed several hundred organisations of this type.6See “Dictionary of Resources”, in Photographic Practices: Towards a Different Image, ed. Stevie Bezencenet and Philip Corrigan (Comedia, 1986), 166–77. Terry Dennett and Jo Spence established Photography Workshop in 1974, merging with Half Moon Gallery the following year to create Half Moon Photography Workshop (HMPW); in 1976 they began to publish Camerawork magazine. This gallery based in East London (later renamed Camerawork) was a central institution of documentary culture. Ten.8 began publishing in 1979, though it was early in the 1980s before it moved leftwards. Side Gallery, a part of Amber collective in Newcastle, opened in 1977 and concentrated on social documentary representations of working-life, including Sirkka-Liisa Konttinen’s work on the Byker housing estate.

Slide packs and introductions to media were produced by various organisations for use in education and community groups. Photo agencies were established to supply the left with images: Report-IFL was active throughout the period (Report was founded in 1946 and IFL in 1970). Network was established in 1981 and Format in 1983. A range of poster and postcard collectives – Film and Poster Collective, Leeds Postcards, Red Women’s Workshop, etc. – emerged, often collaborating with local groups and campaigns; the circulation of these popular images played a significant role in developing class visibility. If you recount the history of documentary politics in the period from the perspective of art history and the avant-garde you are bound to end with a skewed perspective.

It is often forgotten that Camerawork was really a vehicle for documentary in opposition to the commercial photo-comics, contrasting social depiction to the amateur aesthetic of bare breasts and glistening puddles; sparkly commodities and hazy landscapes. During a recent discussion with Carla Mitchell of Four Corners Centre for Film and Photography, she suggested to me that a taxonomy of the magazine’s concerns would include: work, unemployment and poverty; racism; a concern with women’s work, childhood; and a commitment to international struggles in South America (Chile, El Salvador and Nicaragua) as well as Ireland.7Four Corners are currently making the Camerawork archive available online. I would add anti-fascism and media pedagogy to the list and note the international reach also included Bangladesh and Japan. It is an impressive range of subjects. Camerawork showcased such important work as that made by Robert Golden, John Berger/Jean Mohr, The Exit Group, Nick Hedges, Don James and many others. It is worth noting that while many women wrote for Camerawork, the documentary culture represented was heavily masculine. There isn’t a major piece by a female photographer in the first twenty issues. That culture would slowly change.

The early political split in Camerawork was unfortunate – a symptom of different temporalities of radicalisation. The history is contested, but in 1977 Jo Spence was dismissed as the fulltime worker on the magazine and in a messy dispute, Photography Workshop withdrew/were driven out, along with Liz Heron (who was to be a central figure in the Hackney Flashers).8Jo Spence and Terry Dennett, “Ten Years of Photography Workshop”, in Photographic Practices: Towards a Different Images, ed. Stevie Bezencenet and Philip Corrigan (Comedia, 1986), 13–28. There is also an acrimonious exchange of letters between Spence and the other editors. The tension between these committed to a more traditional humanist conception of documentary and those working through a political critique of that practice are real and undeniable, but no one benefited from the rupture. Of course, Spence would never be short of things to do, but she lost a really important platform in the gallery and magazine and they would only have benefited from the energy and commitment of Photography Workshop and women who would be involved in some of the most important photographic work of the decade. In any case, the variety of topics addressed strikes me as genuinely significant. Camerawork could have developed into a hub for radical picture essays. Instead, in the early 1980s as a response to the rise of Neoliberalism, the magazine reinvented itself as part of the Right Euro-communist turn against class associated with the Communist Party of Great Britain’s (CPGB) organ Marxism Today. Camerawork ceased to publish photojournalism and documentary photography.

Briefly, let me gesture towards some of the documentary photography, beyond Camerawork, that offered an ostensive politics of new class characters. Some of this work is well know, such as the work of Chris Killip or Konttinen’s book Byker, which offered a sustained vision of a community in the North East of England where she lived. Other initiatives require research. All I know of The North East Photo Coop – ‘a group of socialist photographers and writers living and working in the North East’ – is the sixty-eight page pamphlet Together We Can Win (1979).

This small book tells the story of two branches of the National Union of Public Employee involved in a pay dispute in the winter of 1978/1979. It is rather grey and cheaply printed, but one can image the role it played in solidifying a class vision among the council and hospital workers involved. Not only a passive reflection of events, this socialist-feminist booklet can be seen as an intervention into the representation and politics of class: it emphasises the role of women in the dispute, making the point that women workers are often marginalised by their union branches, but their concerns are essential to building a successful movement. This small overlooked project is but one molecule in the transformation of attitudes, making gender central to our conception of class. In many ways, the focus on women and work was the enduring legacy of the 1970s. Ethnic differences will pay a prominent role in this post, but I intend to come back to socialist-feminism in documentary in my final one.

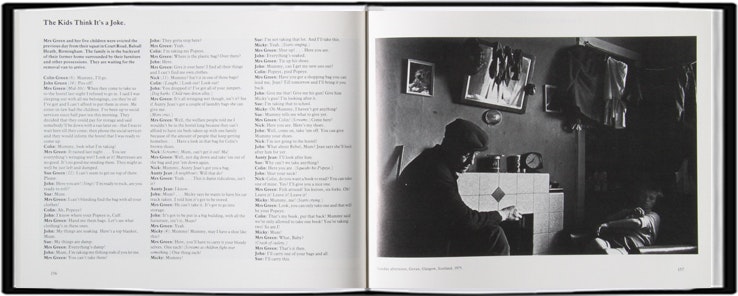

One of the most impressive works of the period is The Exit Photography Group’s Survival Programmes: In Britain’s Inner Cities (1982), which was six years in the making. The group was made up of three photographers: Nicholas Battye, Chris Steele-Perkins and Paul Trevor. Survival Programmes consists of one hundred and four black-and-white photographs, accompanied by transcribed tape-recorded interviews; the book is divided into four sections with fifteen chapters, an introduction and reference matter. Steele-Perkins notes: “We all did some work in London as we all lived there, and we all did some work in Glasgow, but most of Paul’s time was spent in Liverpool, Nick’s in Birmingham and mine in Newcastle, Middlesbrough and Belfast.” The book would justify close attention, but all I can say here is that it is one of the most impressive and complex photographic narratives of this or any other period. Survival Programmes focuses on both work and living conditions in a range of working-class areas; it registers urban dereliction and increasing unemployment, while paying close attention to ethnic and gender distinctions. The book interlaces these images of working people with photographs of the ruling class and close-ups of television screens, featuring key political figures. The final section called ‘Reaction’ features strikes, riots, anti-fascist rallies, events from the civil war in the north of Ireland, West Indian youth clashing with the police. Of course, without the transcribed interviews, it isn’t possible to give a real impression of the book, nevertheless the overall structure of the book counters Stuart Hall’s suggestion that documentary might point to individual situations, but could not reveal the structural conditions that gave rise to them. Survival Programmes looks at capitalist transformation in a period of radical reconstruction and the effect of that process on people’s lives. As if to rebut another criticism of documentary, it shows people fighting back against racism, colonialism and capital. These are not ‘docile subjects’; it is clear that the people depicted were survivors. Exit remains a task to be accomplished.

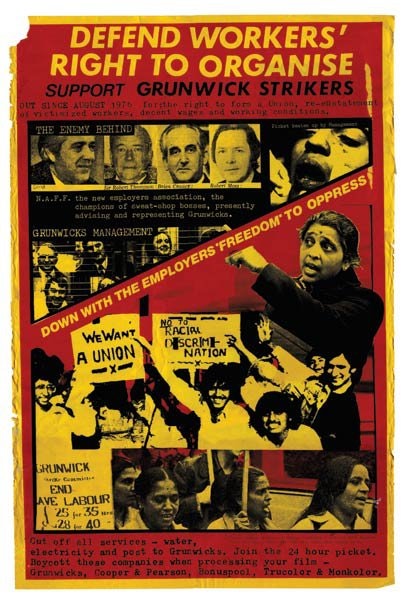

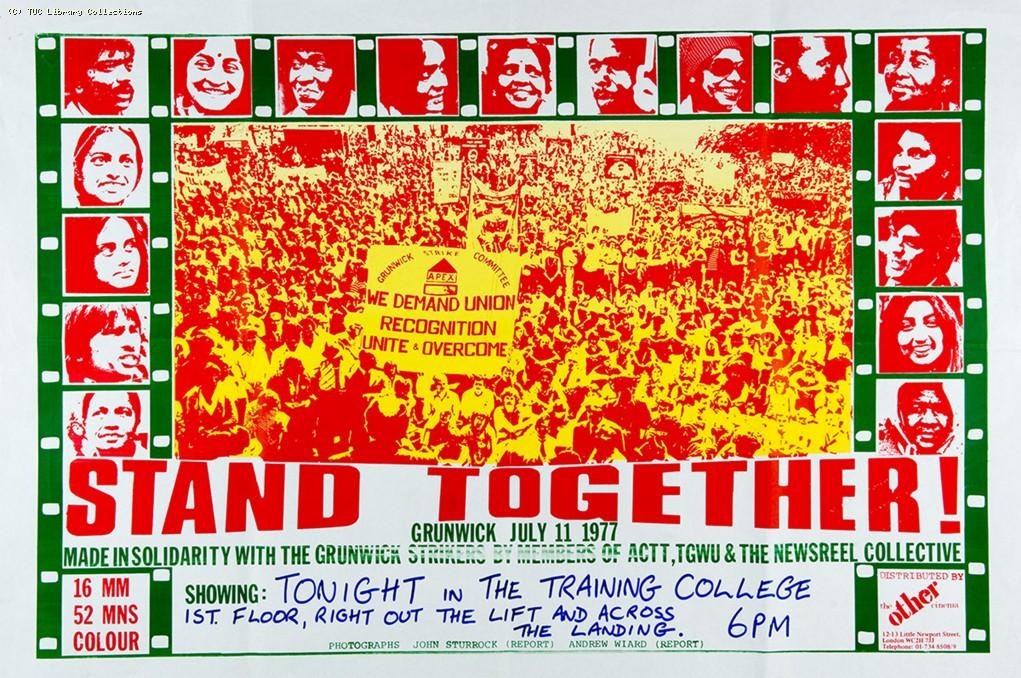

One of the most important points to make is the way the book points to changes in class composition. Works from earlier in the decade – the important films of Cinema Action, for instance, or Byker – portrayed a working-class culture that was almost monolithically white. The presence of working-people of colour in Survival Programmes, the work of Nick Hedges, Robert Golden and Victor Burgin registered an important shift. There had always been religious and ethnic tensions in the British working class, particularly toward the Catholic Irish or East-European Jews. Post-war immigration, particularly from India and the West Indies, bought new constituencies into the labour force. Often confined to low-skilled and low-paid jobs, the Trade Unions regularly regarded these workers as economic competitors, likely to undermine unionised grades. Then as now, the political right stoked divisions. The strike by the largely Indian female workforce at the Grunwick film-processing plant, which lasted from 1976 to 1978, was a pivotal moment. One of the images in the final section of Survival Programmes shows a picket being carried away by the police; almost certainly, it is an image from this dispute.

Despite its ultimate defeat, and there is much that could be said, the Grunwick dispute was important for two reasons: it signified a new militancy among immigrant workers and this was the first occasion that the traditional trade union movement engaged in substantial solidarity with Asian workers. Coaches full of rank-and-file trade union members arrived daily for the fierce struggle that took place outside the plant. Through this period we can see an increasing differentiation within the working class. Workers of colour become increasingly present in the documentary photography of the later 1970s. Nick Hedges and Huw Beynon’s book Born to Work (1982), collecting images from 1976–78, described this as a politics of "new faces". Beynon wrote:

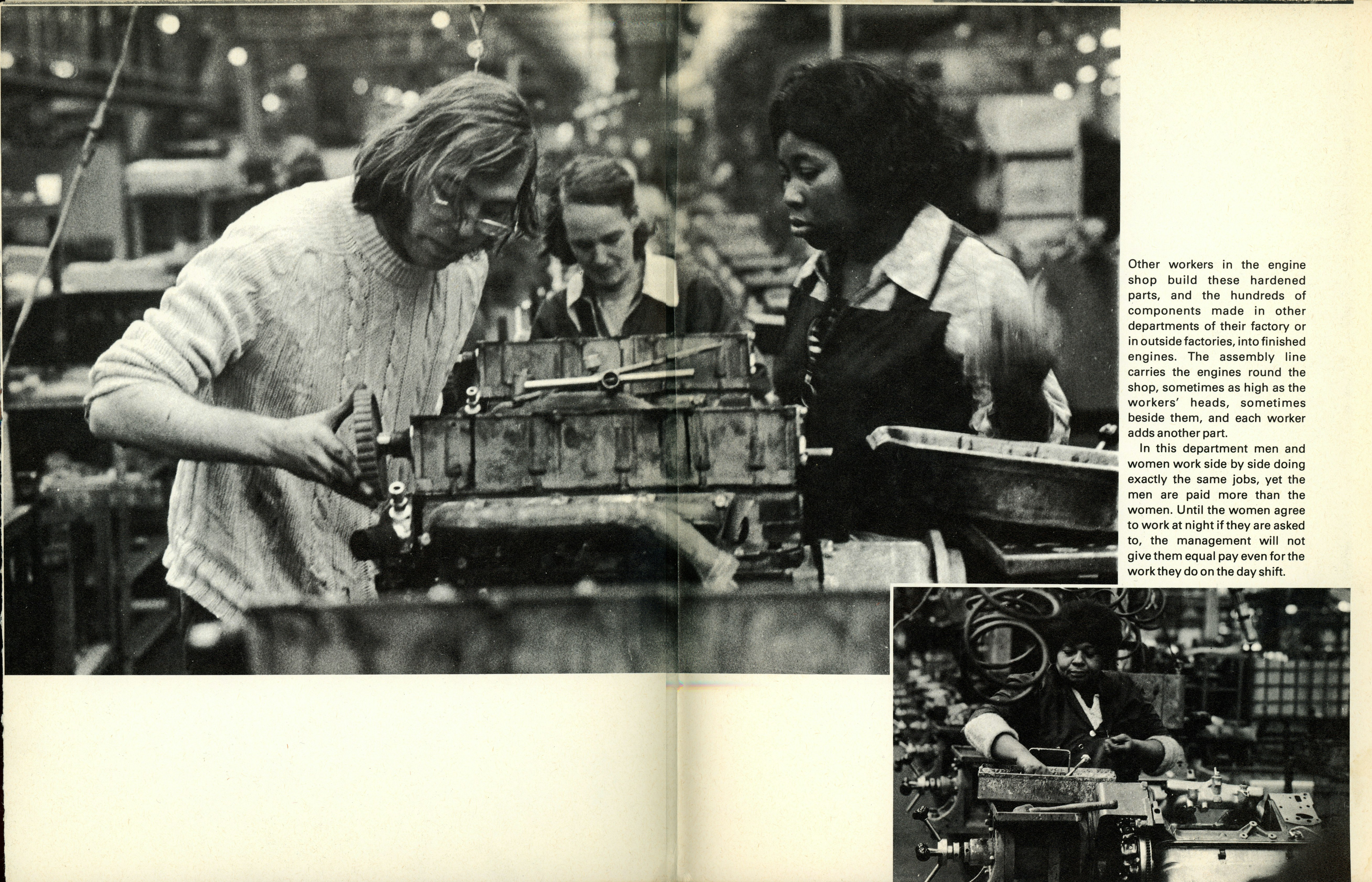

Steel works and pits; docks; railways; and a whole range of metal and engineering workshops were built around a world of men alone. White men alone. And this is something else that is changing. As technical processes altered, so too have the workers who run them. In the 1960s and 1970s new faces appeared on the factory floors in the Midlands. Black faces and female faces.9Nick Hedges and Huw Beynon, Born to Work (Pluto, 1982), 38

Hedges’s pictures bring this new class composition into sight. In my view, this is a politics of photography as performative speech act (cf. Rancière on the count or Butler on Assembly) but one that remains rooted in Marx’s critique of political economy. Photographic works like these reveal any discussion of the ‘white working-class’ as an ideological fig leaf for a politics of resentment.10See the excellent Rethinking Empire event in London, 8 October 2017, with Maya Goodfellow. In our time of refugee crises, economic migration, undocumented persons, borders and walls, it is more important than ever to insist on the presence and visibility of what Peter Linebaugh and Marcus Rediker call the ‘motley proletariat’.

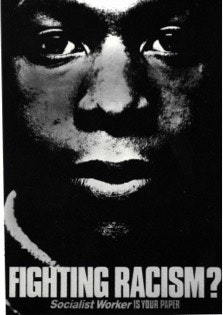

Let me end with a much-overlooked figure, yet one whose work requires serious consideration – Robert Golden. I hope that the recent publication of Home – a compilation of Golden’s photography from the 1970s – will go some way to rectifying the neglect. Golden was an American in London and a committed socialist photographer. He was actively involved with Camerawork from the outset (issue No. 3 features an interview with him by Jo Spence) and his work featured in Photography/Politics: One. I’ve mentioned the innovative poster work he did for the far-left above. I don’t know if there are extant examples and have only seen the reproductions, but these works foreground the changing ethic composition of the working class. One such image is made up of a Helmar Lerski style close-up of the face of a young black man, with the caption ‘Fighting Racism? Socialist Worker Is Your Paper’.

Golden is from Detroit and perhaps this made him more attentive than others to the West-Indian experience in Britain. In any case, his work focused attention on a new multi-ethnic working class in the making and the fight against racism. He also produced a series of children’s photo books with Sarah Cox on the theme of People Working – Car Worker, Dock Worker, Building Worker and Farm Worker.

These books visualise manual work as an important activity worthy of attention, while normalising trade unionism and the role of women and diverse ethnic groups in the workplace. Works of this type are essential for any genuine struggle for hegemony. Again working with the socialist journalist Sarah Cox, Golden published Down the Road: Unemployment and the Fight for the Right to Work (1977). To my knowledge it has not received any serious consideration. At a time of rising unemployment, the book interweaves Golden’s images and the words of Cox with poems, songs and historical photographs from the 1930s. It is a wonderful, campaigning little book that explains the causes of unemployment and advocates the militant fight back. It is a very different book to Survival Programmes, but in its way it is as complexly structured and much more innovative and dialogic than the critics of documentary have allowed for.

What emerges from the works I’ve cited is both the diversity of approaches to documentary, but also work that was often reflexive and dialogic. This was some of the most inventive imagery involved in reinventing the image of class, recognising that working class culture and struggle was not the preserve of white men, but centrally involved women and workers of colour. In our own time when activists are urgently seeking an intersectional opposition to capitalist ecocide, racism, sexism, homophobia and exploitation, it seems well worth looking at those cultural practitioners in the 1970s who created a new motley image of the working class.

Afterword

Only while writing this post did I realise that Nick Hedges’s well-known portrait of a West Indian steel-furnace worker in issue No. 10 of Camerawork (1987) was made in the factory where I briefly had an apprenticeship.

This realisation sent me back to look at Nick Hedges and Huw Beynon’s Born to Work. I must have once known, but had forgotten, that the book is a study of changing patterns of work in the corner of the West Midlands were I grew up. Back to Camerawork and there are three spreads made in my factory. It could easily have been me in any one of the images. An experience, subjective and political, has been rendered invisible by the intellectual turn against documentary.