Undocumented: ‘Intensification, Contraction and Localization’

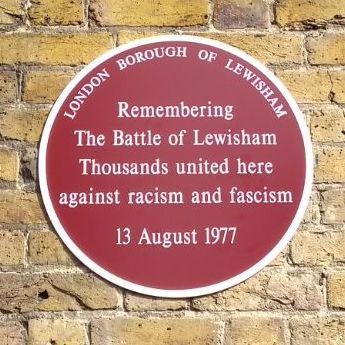

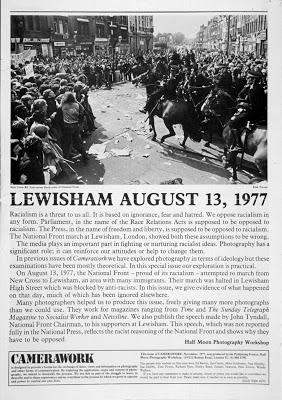

In the week that President Trump tried to pass off assorted white supremacists and storm troopers as equivalent to anti-fascists, an exhibition of photographs commemorating the ‘Battle of Lewisham’ in 1977 opened in Goldsmith College in the South London borough of Lewisham. In August 1977, massed anti-fascists confronted the far-right National Front. The clash in Lewisham was a decisive moment in halting the rise of the Nazi National Front in the UK. They never recovered from the deflating rout they suffered that day. At the time, the black-and-white photographs currently on display at Goldsmiths were the subject of the entire issue No. 8 of the Camerawork. The magazine ran many of these images and offered analysis scrutinising press coverage of the events of that day. At the time, the mainstream media portrayed the anti-racist demonstrators as ‘Red Fascists’, equivalent to the extreme right. It has been a long-term strategy for establishment appeasers (and worse) who wish to present the Right and Left as equally violent threats to establishment politics. Trump is just the latest in a long line to pursue this trick and some appalled journalists should look back through the history of their own publications. Camerawork did a decent job evaluating the media representations of anti-fascists as thugs, but the magazine was embroiled in political disputes of its own and the issue then provoked responses that claimed it was insufficiently committed, standing above the fray. The stakes of documentary mattered.

In my series of posts I’m going to be looking at the 1970s in Britain. In our own moment of increased anti-capitalist and anti-militarist activism, when attention is again falling on global-labour practices, particularly those associated with migrants and women’s precarious labour, it seems like an opportune moment to revisit the last attempt to combine Left politics and documentary photography. First, though, I want to comment on the hiatus between the political moment of the 1970s and our own time. During these core decades of neoliberal hegemony documentary of the kind depicting the events in Lewisham came to be viewed with suspicion by critical intellectuals. This is not to say that documentary photography disappeared from the mainstream media. The institutional spaces of production were maintained and plenty of work appeared on TV and in magazines and books. However, critical discussion of photography shifted markedly against documentary and in favour of staged or constructed images. As with any periodising claim, I should acknowledge that these perspectives overlapped; the criticisms of documentary had been building for some time. The critique of documentary was itself an essential dimension of the radical documentary of the 1970s: whether the ethical concerns with the representation of others (Martha Rosler, Allan Sekula, Jeff Wall); the newly translated writing of Barthes; John Tagg’s historical work on the archives of power; Victor Burgin’s semiotic critique of photo-modernism; Griselda Pollock on ‘Images of Women’; or the urge for the politicisation of documentary (Jo Spence and Terry Dennett). It is clear from the work of Rosler and Sekula that this critique didn’t have to crystallise into a rejection of the documentary mode. However, the solidification of these criticisms into a new common sense was not an inevitable process. It was political defeat, neoliberal triumphalism and associated funding cuts that provided the enormous pressure forming a new consensus in which documentary was seen to be inherently problematic – detached and abstractly humanist, falsely coherent and representing a view from on high, documentary was seen as a masquerade of power-knowledge, in which ‘truth claims’ provided a pretext for the authority of the individuals and institutions that made them. Representations of violence or atrocity were viewed as akin to pornography; the depiction of suffering was criticised as a passive spectator sport in which victims were presented for the pleasure/sympathy of distanced viewers. Witnessing was, somehow, said to be complicit with authority and domination. In contrast, the staged image became co-joined with identity politics and epistemological scepticism.

We can get a flavour of this shift by looking at the intellectual distance separating the two editions of the annual Photography/Politics. Issued at the end of the decade in 1979, Photography/Politics: One – edited by Dennett and Spence with Sylvia Gohl and David Evans of Photography Workshop – is a manual for radical practice and is explicitly pedagogical. Its themes are work, particularly women’s work, housing, poverty, and child-care. The editors are explicit about their commitments; they write: “Our starting point is the class struggle. We assume that it exists (now hidden, now in the open) and that it has economic, cultural and political sites (all overlapping, all continually shifting).” 1Terry Dennett, Jo Spence, Sylvia Gohl and David Evans (eds.), Photography/Politics: One (London Photography Workshop, 1979), I. The focus is on collective action, whether in politics or cultural activism, and it is notable how many collectives feature in the book. Even the advertisements, and there were quite a few of them, echo this collectivism. Photography/Politics: Two (1986) – edited by Patricia Holland, Spence and Simon Watney – was a very different publication, focused as the introduction has it on “The Politics and Sexual Politics of Photography”. Attention fell on advertising and fashion, on images of black homosexuality and the sexuality of children. One-way to characterise this change is to say that the body moved centre stage. Throughout the book there is an evident shift away from the earlier concern with left documentary, in favour of staged images and media analysis. Laura Mulvey’s text “Magnificent Obsession” is symptomatic. I have selected this essay as my example not only because it makes the point, but also because I have great respect for Mulvey’s work as a film-maker and theorist. Her contribution to the volume was a republished exhibition catalogue essay for a group of students who had all studied photography with Victor Burgin at the Polytechnic of Central London: Karen Knorr, Mark Lewis, Olivier Richon, Geoff Miles and Mitra Tabrizian. Mulvey notes: “Both Mark Lewis and Mitra Tabrizian started off as documentary photographers with a strong commitment to realism. A shift in concern towards sexual politics, under the influence of feminism and psychoanalysis, has produced an equivalent shift in style and approach to the photographic image; the latter is now freed to convey an invisible reality, dream and fantasy.” 2 Laura Mulvey, “Magnificent Obsession”, Photography/Politics: Two, ed. Patricia Holland, Jo Spence and Simon Watney (London: Comedia, 1986), 142–52, quote 145. Presumably, the point is that staged images, engaging with media imagery, allowed photographers to explore the formation of gendered subjectivity in a way that realism did not. This argument does now feel like a period ‘structure of feeling’. From the perspective of the recent engagement with social reproduction, biopolitics, the re-emergence of explicitly socialist forms of feminism (I’ll return to these issues in my final post) and, indeed, the renewed prominence of documentary or photographic realism in theory and practice, there appears no necessary linkage between the terms Mulvey establishes. I’m not arguing that these issues aren’t important, but I do think there is no evident reason why sexual politics and feminism should be coupled to psychoanalysis or why these couplets involve severing any link to documentary realism, in favour of what Mulvey calls “invisible reality, dream and fantasy”. 3Ibid. Nor for that matter, is it apparent why so much focus fell on film noir. What is clear is that the terms of the debate had changed as collective politics gave way to concerns with identity. What happened in this seven-year hiatus is a story that is yet to be fully recounted. Nevertheless, the drift is clear: from class to subjectivity; from activism to academic analysis.

It was a strange time.

Reflecting on European and North American social thought during this period, Ellen Meiksins Wood argued that the over-arching ideology of the 1980s was “the retreat from class”. 4Ellen Meiksins Wood, The Retreat From Class: A New True Socialism (Verso, 1986). The perspectives that came to dominate intellectual debate all entailed the displacement of politics based on social class with some other constituency. Whether in the micro-politics of Foucault, forms of identity politics, or claims for new forms of popular alliance, attention shifted away from a focus on class and the state and towards an engagement with signification and, what Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, called “the plurality and indeterminacy of the social”. 5Ernesto Laclau and Chantal Mouffe, Hegemony and Socialist Strategy: Towards a Radical Democratic Politics (Verso, 1985), 144. The more culturalist wing of this theoretical formation was preoccupied with the social construction of ‘the real’. My argument is that documentary and class are closely entwined. Subalterns are the heart of documentary practice, as subjects and imagined producers, and periods when social class has been at the heart of public debate have produced strong documentary movements. The 1930s and 1970s provide the exemplary moments for this claim. In contrast, the period of the 1980s and 1990s witnessed a low point or critical esteem of documentary. The invisibility of the working population, the idea of the end of class, the disappearance of industrial work, or the shift in focus from the working class to the ‘underclass’, during the core years of neoliberalism are, I suggest, mixed up with the rejection of documentary.

The antipathy to documentary has declined markedly in recent times. Over the last fifteen years there has been a revival of intellectual interest in the documentary work, primarily associated with the circuit of art galleries and biennials. Documentary is back, while being confined in the prison house of art. As evidence for this revival of interest, consider the current prominence of video essays by Chris Marker, Harun Farocki and Sekula or the newer work in the same form by Ursula Biemann, Phil Collins, Luke Fowler, Oliver Ressler, Maria Ruido and Hito Steyerl. There have also been important photo projects by George Osodi, Geert van Kesteren, Trevor Paglen, Ahlam Shibli, Sekula (again) and the excellent Activestills group in Palestine/Israel. We have seen an increasing torrent of publications recovering the hidden legacies of radical or reflexive documentary and a significant outpouring of new books concerned with bearing witness to acts of violence or atrocity and speaking back to power: think of the essay collection Greenroom (eds. Hito Steyerl and Maria Lind), Ariella Azoulay’s Civil Contract and Civil Imagination, Susan Sontag’s Regarding the Pain of Others and John Roberts’s Photography and Its Violations. There are further books titled Human Rights in Camera, The Cruel Radiance and Seeing Witness. Whatever the differences, or strengths and weaknesses, of this literature, it attests to a new cultural mood. Important exhibitions committed to, or substantially engaged with, documentary can also be cited. Okwui Enwezor’s Documenta 11 in 2002 might be viewed as initiating this sequence, but mention should be made of Julian Stallabrass’s Brighton photo-biennial of 2008, Memory of Fire: Images of War and The War of Images. Two exhibitions curated by Jorge Ribalta’s at the Museo Reina Sofía in Madrid have been vital tributaries for this new agenda: A Hard, Merciless Light (2011) – dedicated to the worker-photography movement of the 1930s – and Not Yet: On the Reinvention of Documentary and the Critique of Modernism (2015) that took its impetus for considering the critical work of the 1970s from Allan Sekula’s important essay. Listing various film programmes would just amplify this growing sensibility.

Not Yet: On the Reinvention of Documentary and the Critique of Modernism. Installation view at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2015

Not Yet: On the Reinvention of Documentary and the Critique of Modernism. Installation view at Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía, 2015Some commentators have noted that the shift into these institutions is directly linked to the neo-liberal transformation of public broadcasting; the replacement of serious reporting by syndicated news – often little more than corporate press releases or advertising copy – and picture capture from phone technology. If documentary, in its traditional institutions, has been undermined by this ‘flat earth news’, there is now an increased interest among critical intellectuals and artists in witnessing and truth-telling, or speaking back to power. It might be better to say that the impetus for this critical shift has been the over-determined conjuncture of neoliberal media, economic crisis, the wars of intervention, and violent regime change that are essential elements of the neoliberal polity. Certainly, no one now seems interested in large digitally-manipulated photographs and only the foolhardy or the utterly callous would now subscribe to Jean Baudrillard’s argument that the first Gulf war was a media event – a fiction created by the mass-media and infused by the attitudes of computer war games. Today, such epistemological scepticism seems like a luxury for the morally idle.

The revival of documentary practice has been accompanied by a key shift in thinking about photography. For instance, Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites have argued that documentary visibility is an important condition for public debate. 6Robert Hariman and John Louis Lucaites, No Caption Needed: Iconic Photographs, Public Culture, and Liberal Democracy (University of Chicago Press, 2007). For them, documentary production is an essential component of liberal democracy, but we can extend their point and suggest the documentary mode is a vital element in any democratic polity – documentary is, first and foremost, ostensive, it points to the overlooked or occluded; it draws into view realities that capitalism would prefer to remain hidden and unvoiced. Azoulay’s claims for a fourfold encounter – camera/subject/photographer/viewer – and the importance of ‘appearance’ in politics is, perhaps, a better-known account. I’m not going to discuss here Azoulay’s reliance on Arendt’s discussion of the Polis, its inclusions and exclusions or related arguments in the work of Judith Butler and Jacques Rancière: I intend to engage that debate substantively elsewhere. My view is that these arguments need radical reconstructing, but the core point is certainly correct – appearance, or visibility, is a key condition of any political claim, enabling the excluded to stake a claim to participation in political life. Political constituencies come into being around this kind of appearance and documentary has played a central role in pointing to the occluded. In this sense, the intellectuals’ abandonment of class (and documentary) has been a self-fulfilling prophesy. But suddenly, talk of the pornography of violence has given way to an instance on ethical necessity of seeing the effects of violence; in the case of Azoulay, this has even entailed extensive discussion of invisible images held in state archives or the non-existent pictures of rape. For me, however, the heart of documentary practice is not Azoulay’s ‘civil imagination’, but splitting, by which I mean the forms of visibility that might initiate political bifurcation and the marking of distinct social agendas. Documentary provides one significant site for the division of interests that produce politics. My point is that the abandonment of documentary was the form the retreat from class took in photography (and film); it amplified that flight, removing important conditions for dialogic struggle. As Rancière rightly argues, when collective notions of ‘class’ or ‘people’ are abandoned, spurious collectivities such as ‘race’ occupy the void. 7Jacques Rancière, Disagreement: Politics and Philosophy (University of Minnesota Press, 1999). It is now obvious that religious revivalism is another contender for the vacuum left by the retreat from class. We have been paying a very heavy price for this intellectual neglect that began during the 1980s. I guess you get the enemy you deserve! To adapt Alain Badiou’s terms from The Rebirth of History, documentary visibility entails a truth claim that provides a locus for: “intensification, contraction and localization”. 8Alain Badiou, The Rebirth of History: Times of Riots and Uprising (Verso, 2012), 90f. Appearance is constitutive of political discourse. It is not that versions of these arguments have not been raised previously: for a long time John Roberts has been insisting on the ostensive, realist dimension of the photograph and I outlined a version of the dialogic photographic encounter in 1990. 9John Roberts, Photography and Its Violations (Columbia University Press, 2014); Steve Edwards, “The Machines Dialogue“, Oxford Art Journal, 12, 1 (1990), 63–76. The difference, I think, is that the new advocates for claims of this type have found a receptive audience. The argument was required by a new constituency of viewers and readers.

In concluding this first post, I think we should ask, is the emptying of politics – real social divisions condensed into a stage-managed media circus of sound bites, spin, vapid style and photo-opportunities – alongside the decline in the intellectual credibility of documentary a mere coincidence? Might we not see a deeper connection between post-politics and the dismissal of documentary; is not this couplet rooted in the same fear of social reality or hatred of democracy?