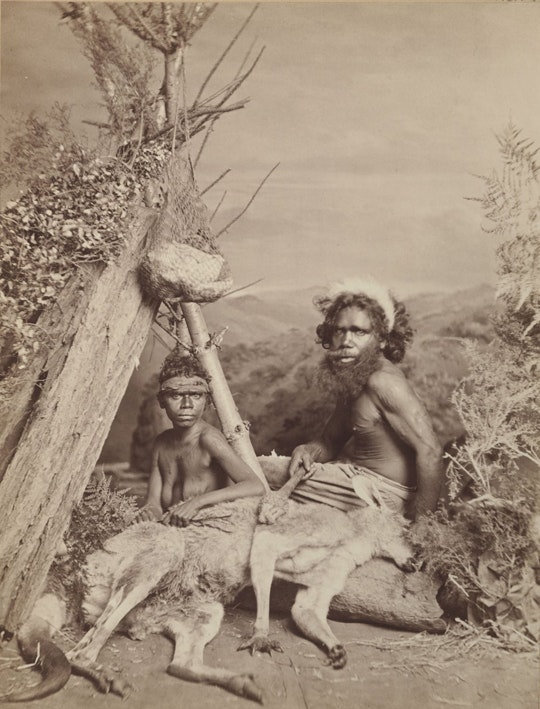

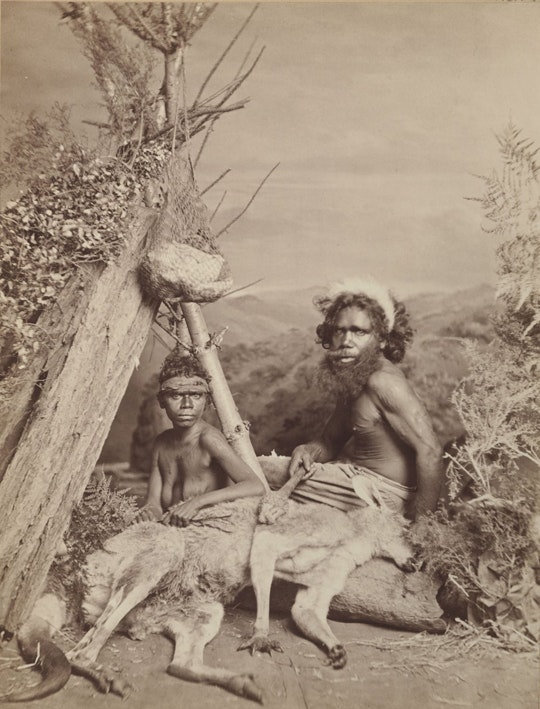

It is equally established that classifications systems have ideological origins which have become naturalised within institutional practices and agendas. Language expands or controls the ranges of experiences possible within institutions. Words of description, representation, and interpretation control the content of knowledge as well as understanding. As Derrida has famously argued, text communicates between absent authors and unknown audiences “spewing out its manifold significations, connotations and implications.” 4 Quoted in Willie Thompson, Postmodernism and History (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2004), 10.While the text is unstable between ‘author’ and ‘reader’ and it is well-recognised that researchers bring their own agendas to the practices of viewing within museums, at the same time institutions shape and manage the kinds of knowledge aligned with their thought landscapes, creating the central naturalised realities which mediate understandings through the reproduction of disciplinary landscapes in order to create a stability of meaning. This is now a cultural theory commonplace of course. But it has very real material consequences for the way photographs work in institutions. The apparatus of photographic description comes to carry an authority and credibility. They are made believable as one sort of thing as registers and catalogues “track the rituals of accession and disciplinary assimilation”. At stake in styles of communication within the apparently neutral tools of finding aids, access and storage “cover complex notions of cognition, memory and excavation” which are both material and symbolic. 5 Francis X. Blouin and William G. Rosenberg, Processing the Past: Contesting Authority in History and the Archives (Oxford: OUP 2011), 4. See also Geoffrey N. Swinney, “What Do We Know About What We Know? The Museum Register as Museum Object", in The Thing About Museums, ed. Sandra Dudley (London: Routledge 2012), 31–46.To what classes of knowledge is this object admitted, from which is it excluded?