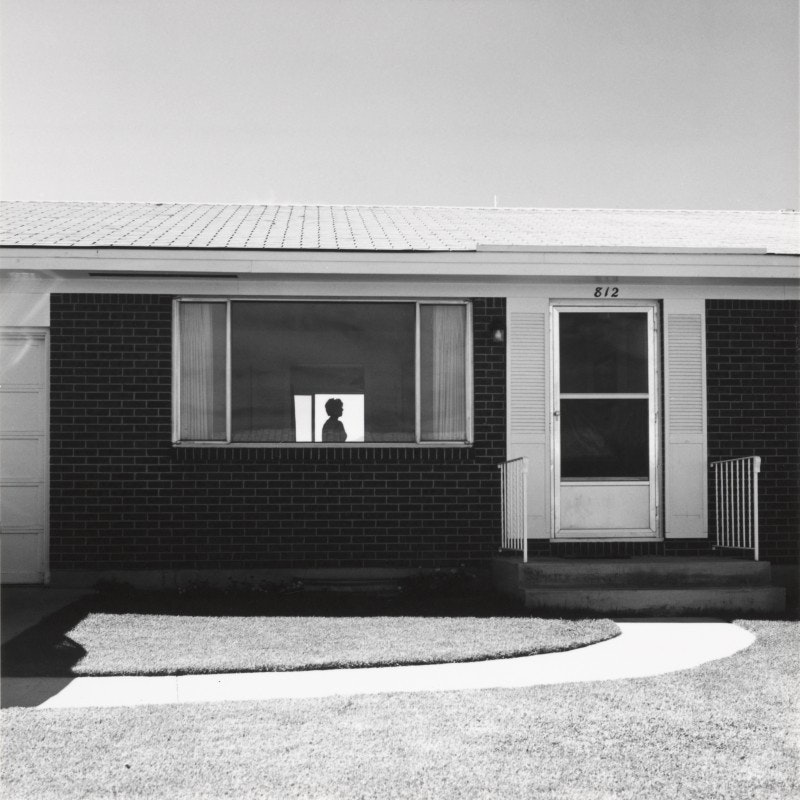

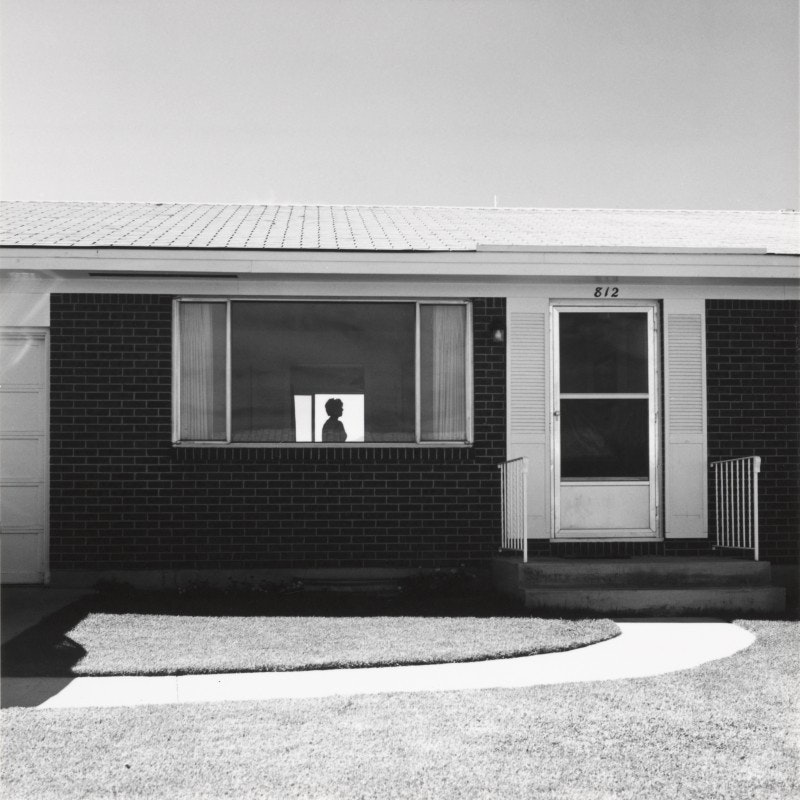

Carefully framed, starkly rendered, impeccably printed, the isolated figure seen through the window of the tract house performs the self-referential trope so common in modernist photography (cf., the window as photograph, the picture within the picture, etc.). Similarly, the evocation of the bleakness, anomie, and cheap architecture of l’Amérique profonde pretends to a kind of cultural critique whose superficiality is usefully contrasted with, for example, Dan Graham’s 1965 Homes for America. Where Adams depicts the suburban landscape in the language of [photographic] art, Graham employed the cheapest of color prints, the most blunt and artless framing, and used as his “support,” the pages of a magazine. And, not least, included a textual element. Adams, however, is a photographer who truly believes in a kind of theology of the image, such that to photographically represent something is thought to automatically convey some (well-)intended meaning. Thus, to take pictures of deforestation is imagined to be a brief for ecological responsibility. Nowhere is this attitude better illustrated than in his 1981 series Our Lives and Our Children (who is “Our”?) in which white Coloradans—with children—photographed in a parking lot of a mall, are meant as a protest against the nearby presence of the dangerous, accident-prone, and ultimately cashiered Rocky Flats Plant—a nuclear production station whose site is still contaminated.