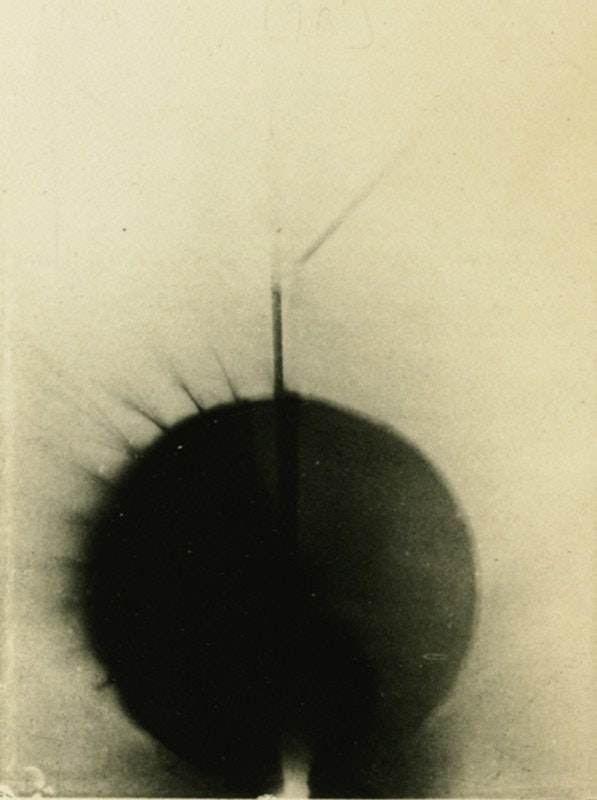

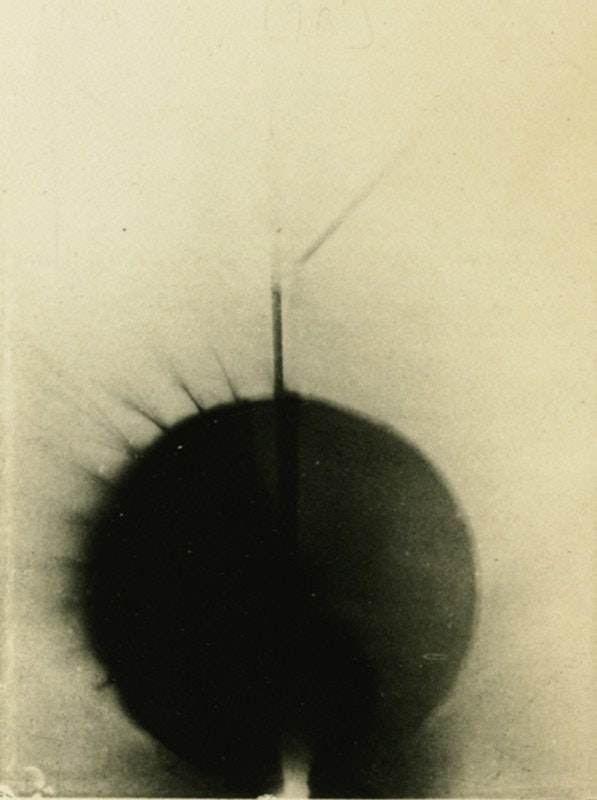

One way of looking at the problem would make it easier. In an article published in May 2000, André Gunthert discusses photography as a particular sort of human knowledge; he bases his description of scientific photography not on some inherent technical quality in photography, but on the reception of the photographs. (A. Gunthert, "La rétine du savant: La fonction heuristique de la photographie", Études Photographiques 7, May 2000). Like Appadurai's commodities, bodies of knowledge appear and disappear. They are constituted by the society of scientists that agree that the object is indeed an object in the way photography represents it. When research or concepts move on, as they soon did in the first decade of the twentieth century, the photograph might no longer represent the object, and it becomes obsolete. Photography then, could be said to generate objects. Not objects in the conventional sense that they exist in the real world, but objects that normally have no corporeal presence. These might be physical phenomena, or, taking the example of Becquerel, however, they might also be scientific concepts.