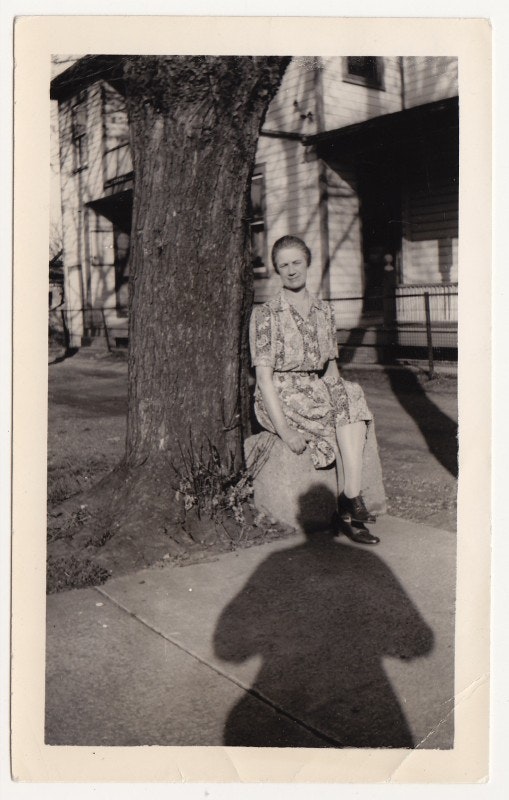

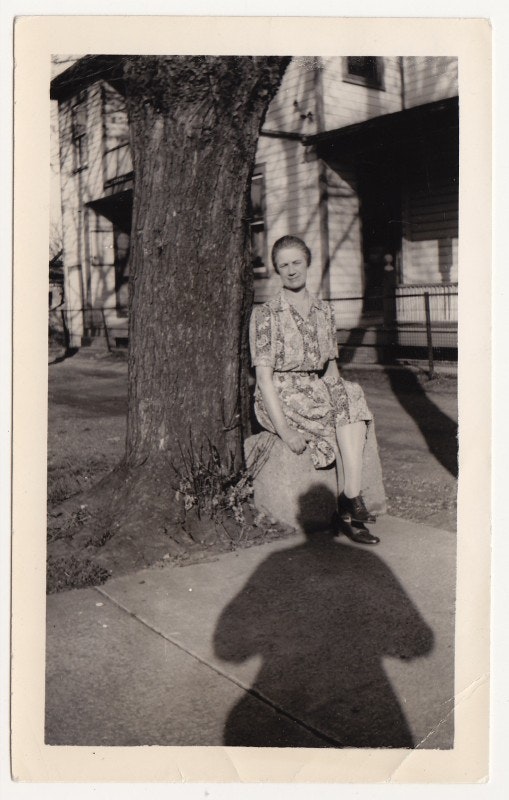

As we have seen, reproduction has exponentially increased the audience for certain photographs, thus securing photography’s presence in the culture. But the price for this has been a disconnection of the photographic image from photography itself, blurring any firm distinction of form and substance, and introducing the post-medium condition that digital technologies have since only exacerbated and prolonged.In other words, once it was harnessed to the engine of reproducibility, photography could not help but be haunted by its own ghosts. Much the same could be said about those subjected to it. A photographic portrait, for example, affirms one’s place in time and space but also functions to divide the sitter from him or her self, creating an experience of temporal and spatial dislocation that is distinctively photographic and peculiarly modern. Such a portrait is an image seemingly produced by the very bodies that are represented, as if those bodies have left a part of themselves, as a visual trace, on a two-dimensional surface. Not necessarily a truthful rendition of appearance or personality, a photographic portrait is nevertheless an indisputable certification of each photographed subject’s presence in some past moment. The photograph both confirms the reality of a sitter’s existence and remembers it, potentially surviving as a fragile talisman of that existence even after its subject has passed on. But that very same photograph, by placing its referent indisputably in the past, is itself a kind of mini-death sentence, a prediction of the subject’s ultimate demise at some future time. That’s because photographs certify times past but also time’s inevitable passing--and with it, our own. Each portrait therefore embodies a paradoxical message, speaking simultaneously of life and death even while suspending the subject somewhere in between.