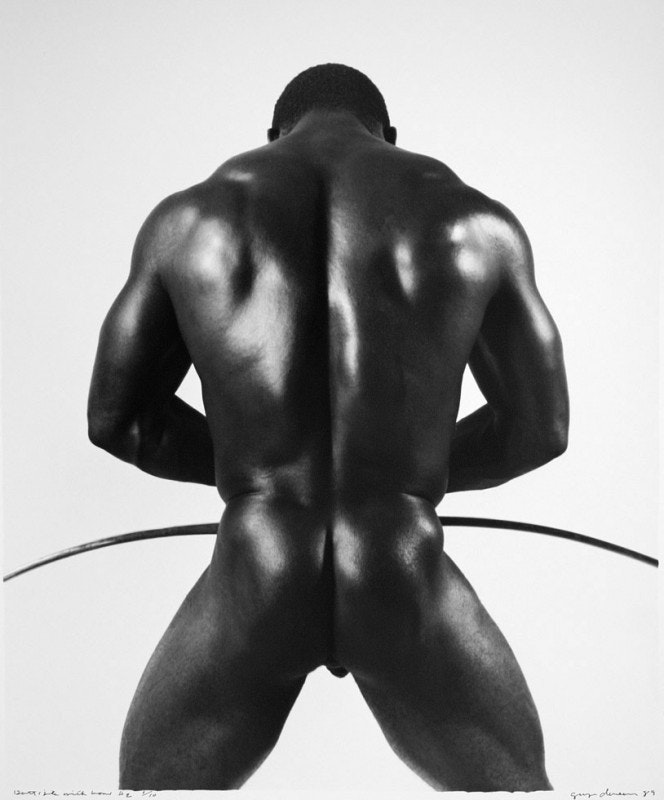

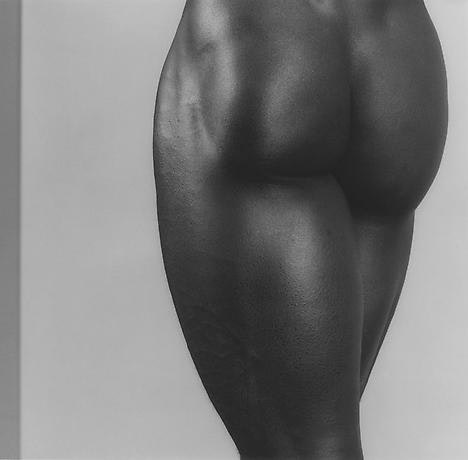

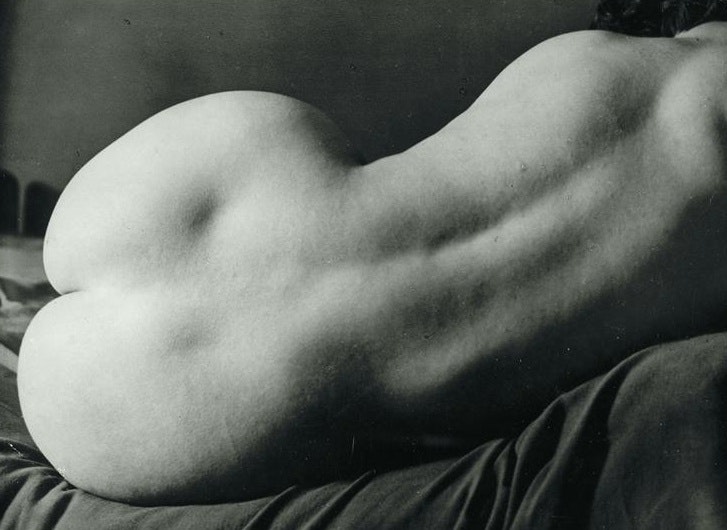

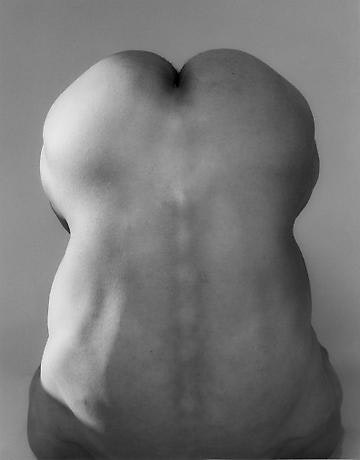

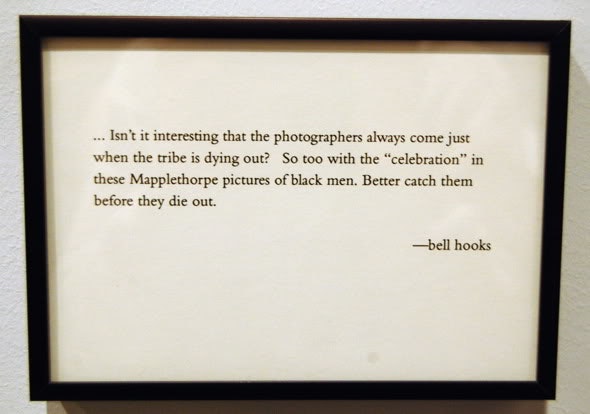

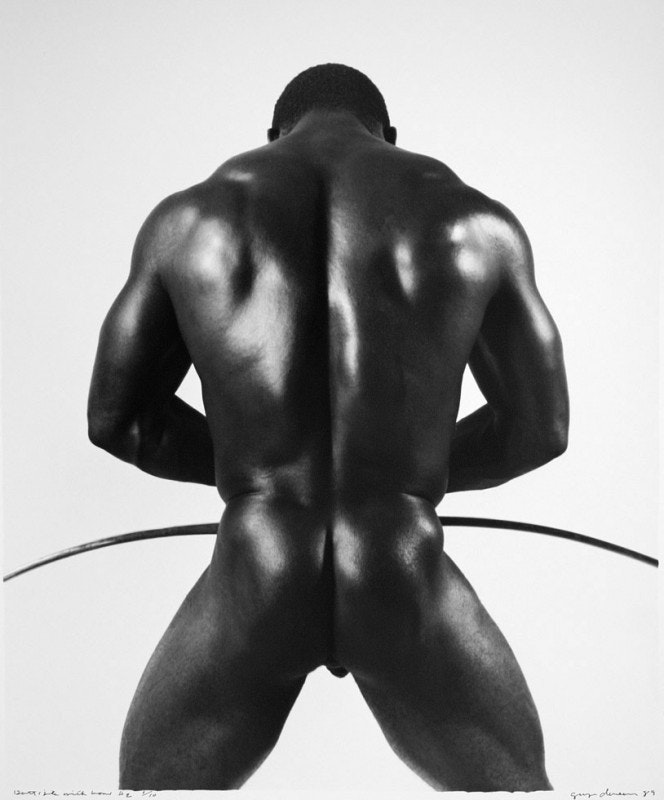

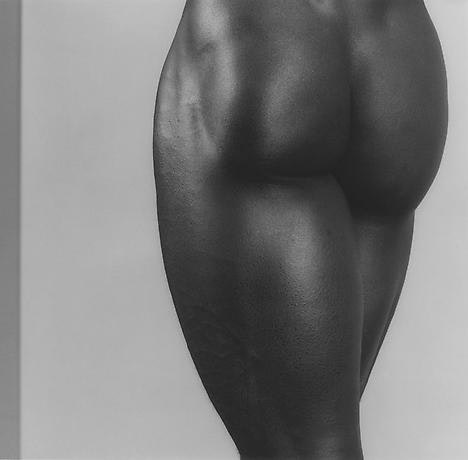

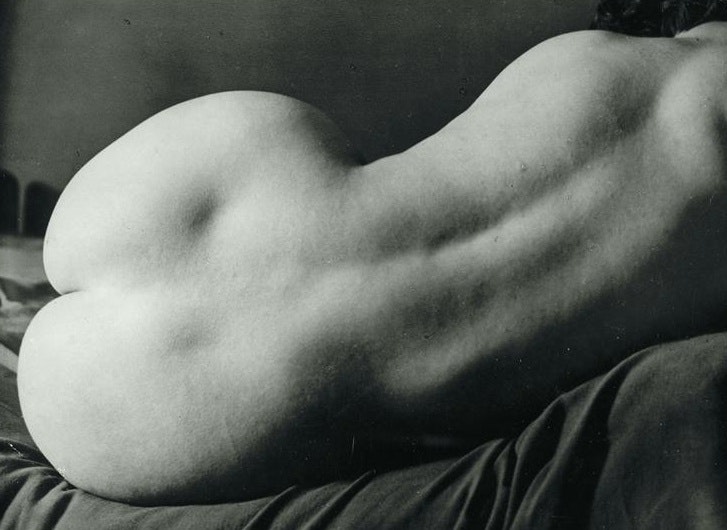

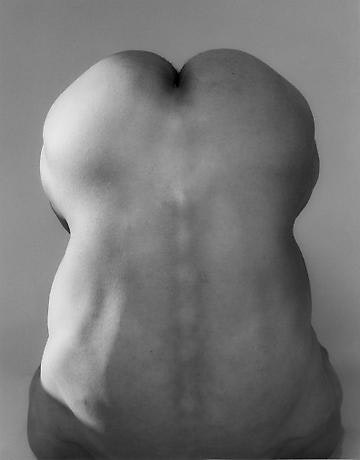

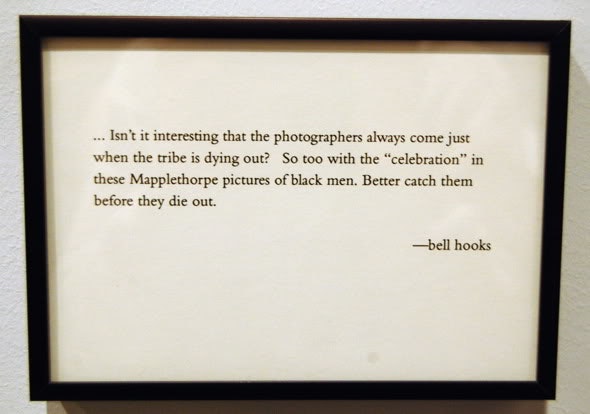

That Mercer’s reconsideration of his earlier essay is longer than the initial one (which is, obviously, far more polemical) is suggestive. Much of the argumentation is strained, circuitous, hard to pin down, and, as he freely concedes, personal. But asserting that the nude (sex unspecified, but surely he means the female nude) is ipso facto a sign of elite culture, obscures the fact that it is largely dead as an artistic genre (for good reason) and more to the point, it is precisely feminist theory, criticism and practice that helped to make it obsolete. (I am not here referring to the naked body as such, whether in performance or other media). In other words, if feminism teaches us anything in terms of the politics of corporeal representation, especially photographic representation, it is that relations of domination and subordination, ideologies of gender, voyeurism, objectification—and preeminently affirmations of fetishistic desire, are inevitably sustained if they are not subverted, de-sublimated, or otherwise “ruined.” Mercer’s argument as a gay male subject who finds his desire affirmed in Mapplethorpe’s images is thus perhaps analogous to those gay women who find erotic or pornographic representations of women pleasurable or arousing. My point is not that they shouldn’t, much less that such imagery is “bad” and should be censored, but how such imagery operates for gay women or women in general, has little to do with how it operates in general. Here, as elsewhere, context counts, but the context of Mapplethorpe’s current exhibitions in Paris, or better, its total absence of context other than its museological finery, that is, its mode of address, is a major problem. A serious presentation of Mapplethorpe’s production, instead of exhibiting his kitsch religious artifacts or juvenilia, might well have included his contemporaries working with similar subjects in a similar milieu (e.g., Hujar, Dureau, Mark Morrisroe, etc.), possibly some Tom of Finland graphics and gay magazines to link with mass cultural forms, and crucially, the programming of such works as Marlon Riggs’ Tongues Untied, Isaac Julian’s Looking for Langston, and mixed media from activist collectives like Act-Up and other organizations.