Cold Case No. 3. Post-photographic Melancholia: Nationalism and Identity

It is indeed a different nature that speaks to the camera from the one which addresses the eye; different above all in the sense that instead of a space worked through by a human consciousness there appears one which is affected unconsciously.

– Walter Benjamin, ‘A Short History of Photography’ (1931)

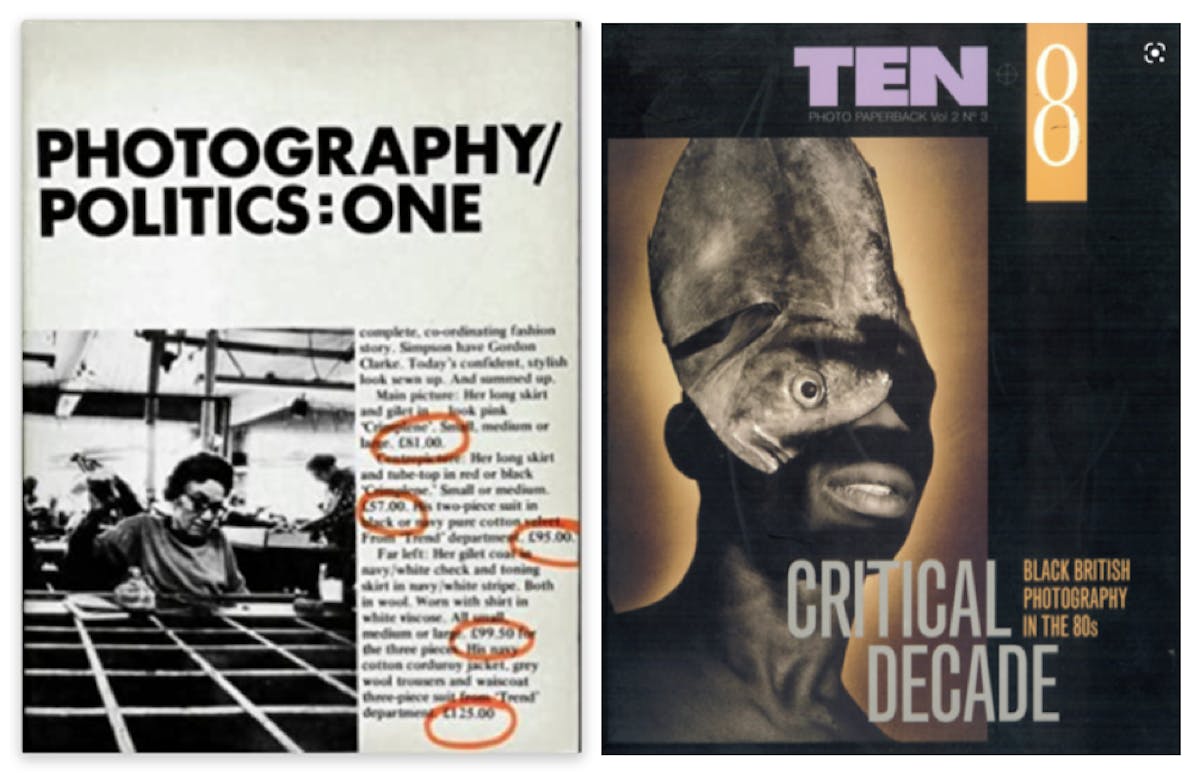

This is the last in this series of cold cases for Still Searching... My overall aim has been to animate readers to argue and debate the polemic of Forget Photography. Forgetting photography is a thought experiment and a critique of photographic theory and culture. Forgetting is a strategy enabling a view of photography from a future present. Photography is no longer continuous with the mode of image production and circulation; rather, it is finally a historical medium of heritage. Two serious issues arise from the discontinuity of photography and the current technical image. Firstly, the computational networked image is still promoted in terms of the language and conventions of photography, which only masks the new networked condition of the image. Secondly, and paradoxically, in computational culture photography proliferates as the dominant language of the representational real. Several important questions and new research agendas arise from this situation. What can photographic collections and archives tell us about the extended apparatus of the medium, now that the historical period of the mechanical analogue has passed? In what ways does photography in its corporeal and cultural disguises persist? Where can post-photographic scholarship go next?

In this case I briefly outline a possible approach to understanding the zombie state of British photography as a specific affect of postcolonial melancholia, a cultural condition of mourning without recognition of what has been lost. In Mourning and Melancholia Sigmund Freud defines melancholy and mourning as two different responses to loss. 2Sigmund Freud, Mourning and Melancholia (1917; London: Penguin Classics, 2005). Unlike the process of conscious mourning, which finally reconciles loss, melancholy is a pathology of the unconscious in which separation from an object of attachment remains incomplete. Instead of being able to redirect desire to other objects of affection, the melancholic directs the excess of desire inward towards an identification with what has been lost, creating an unrecognised inner division and unresolved conflict. The possibility of a post-photographic melancholia briefly sketched here draws upon the idea of the unconscious, not in Freud’s sense of an individual pathology, but in its cultural connotations. Post-photographic melancholia is a variation on Paul Gilroy’s expansion of the idea of postcolonial melancholia, which provided new insights into British nationalism and racism. 3Paul Gilroy, ‘The Closed Circle of Britain’s Postcolonial Melancholia’, in The Literature of Melancholia: Early Modern to Postmodern, ed. Martin Middeke and Christina Wald (New York: Macmillan, 2010), 187–204. In Postcolonial Melancholia Gilroy adapts Freud’s psychoanalytic definition as the loss of an imagined omnipotence and ‘an unhealthy and destructive postimperial hungering for renewed greatness.’ 4Paul Gilroy, Postcolonial Melancholia (New York: Columbia University Press, 2005), 95.

Post-photographic melancholia in Britain involves both the loss of Britain’s once powerful empire and the loss of photography’s historic role in defining that reality through its representation of British identity. In practical terms, post-photographic melancholia is a collective behaviour of imagined identity, performed through a triad of apparatus, photographer and subject.

Post-photographic melancholia is confined by its unconscious condition to repeating loss in the quest for white national identity, whilst marginalising and stereotyping everyone who is classified as non-white. This is a continuation of the colonial lens of photography, now turned back upon itself and the photographer in an internalised and misplaced gaze. Post-photographic melancholia defines a much wider and longer image agenda, focused upon and limited to the photographic subject. From the archival gaze of individually photographed slaves to the selfie, photography repeats a politics of (racial) identity rather than a politics of emancipation. Notwithstanding, Shawn Michelle Smith and Sharon Sliwinski point out that ‘postcolonial scholars have subsequently demonstrated that photography also allows for slippages and resistances, forms of double mimesis, disidentification, and double consciousness that resist official, normative strategies of categorization and containment’. 12Shawn Michelle Smith and Sharon Sliwinski (eds.), Photography and the Optical Unconscious (Durham, NC:Duke University Press, 2017), 3. Thus, there has always been a resistant gaze in photographic representation, albeit one after the fact.

As Gilroy also says, ‘Political nationalism has long been recognized as requiring systematic forgetting.’ 14Ibid, 2.