Women and Work

It has often been claimed that the radical documentary practice of the 1970s attended to class politics to the exclusion of gender. This was one of the core arguments for a staged practice of photography. However, it is notable how much of the documentary production of the period was focussed on women’s labour. Victor Burgin’s UK76 includes a photograph of an Asian woman working in a textile factory and Photography Workshop and Jo Spence were centrally involved with the education of working-class women in east London. I’ll discuss the Hackney Flashers below. The Women and Work exhibition (1975) by Margaret Harrison, Kay Hunt and Mary Kelly employed photographs, text and audio to tell the story of gendered-wage differentials and hierarchy of job grades in an East London metal factory. In photo-text works, Alexis Hunter addressed the left’s lack of interest in domestic labour. There must have been plenty of incidental publications that look at the role of women in trade unions like Together We Can Win, which I discussed in my third post. The documentary exhibition Women on Women held at Half Moon Gallery (1972) is less well-known than other works, but significant in registering an emergent structure of feeling. There was also a Camerawork exhibition called Gaining Momentum. 8 Women Photograph Women, but I haven’t been able to find out any more. The central place of children in Camerawork magazine also belongs in this sequence. Three Perspectives on Photography and Photography/Politics: One were, in many ways, distillations of this trend. The film work in this mode is probably better known than the photography. Films included Women of the Rhondda (1973); The Amazing Equal Play Show (1974); Nightcleaners, Part 1 (1975); Laura Mulvey and Peter Wollen’s Riddles of the Sphinx (1977); So That You Can Live (1982); and Susan Clayton and Jonathan Curling’s The Song of the Shirt (1979). All have some relation to an expanded sense of documentary. Sometimes this work is conflated with Conceptual art, and while there are clear overlaps, it is sufficiently distinct to require another kind of consideration. Mary Kelly’s Antepartum (1973) is a short film presented in a loop that shows the artist stroking her pregnant stomach. Even Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973–79), as the title suggests, belongs in this sequence. As we have seen, the work of Nick Hedges and the Exit Photography Group also zoom in on working-class women.

‘Women’s labour’ is a peculiarly doubled term and much of the new documentary attended to the role of women in both social reproduction and wage labour. Whereas the representation of sexuality dominated debates in the 1980s, childcare and equal pay were the defining issues of the period. In 1970 the British government passed the Equal Pay Act, legislating the same pay for men and women doing the same job. The law may have created a level field, but attaining parity required a great deal of further struggle. The same year the Women’s Liberation Movement (WLM) held its first conference at Ruskin College. The demands were equal pay; equal educational and job opportunities; free contraception and abortion on demand; and free 24-hour nurseries. Through to 1978, there would be ten WLM conferences and these four programmatic demands expanded to seven. It is notable, though, that the stated aims of the WLM focus on work and social reproduction. The documentary photography of the period did so too. Richard Greenhill’s centrepiece in Camerawork No. 6 is emblematic of this period, because it includes both forms of labour – the woman who has just given birth and the waged reproductive labour of the midwife.

This is not to say that new documentary wasn’t engaged with the problem of how to depict women or how to avoid the voyeurism of the mass media and treat women, particularly working-class women, as active political subjects. In a period of mass social struggle the focus was on the intersection of class and gender. As Liz Heron of the Hackney Flashers noted, the group were clear about “fighting class oppression as well as women’s oppression and showing the two as mutually reinforcing”.1Liz Heron, “Hackney Flashers Collective: Who’s Still Holding the Camera?”, Photography/Politics: One, eds. Jo Spence and Terry Dennett (Photography Workshop, 1979), 128. With the retreat from class that occurred during the 1980s this concern was to drop out of mainstream debates on feminist art and film, only recently resurfacing with renewed interest in social reproduction, intersectionality, sex work and precarious labour. The experience of neoliberalism and political defeat saw these poles pull apart; the tensions slackened and the concerns of working-class women were marginalised for an extended period.

In this final post, I’m going to take the work of the Hackney Flashers as my chief example of a practice focused on both wage labour and social reproduction. The Hackney Flashers emerged when Photography Workshop were looking for photographers to work on an exhibition on women and work in Hackney (a municipal borough in North-East London, where I live) as part of the anniversary of the local Trades Council with the incongruous title 75 years of Brotherhood. The group worked as a socialist-feminist collective and produced educational and campaigning material including the two well-known exhibitions Women and Work (1975) and Who’s Holding the Baby (1978).2For a history of the Hackney Flashers and membership, see https://hackneyflashers.com/history/ (accessed 23 October 2017). These multi-panel photo-text exhibitions appeared in a range of alternative and community venues: Hackney Town Hall, health centres, libraries, schools, trades union and feminist events. At the end of the decade the Hackney Flashers produced a slide pack: “Domestic Labour and Visual Representation”. Images were recycled across the various projects and refunctioned for other purposes: the woman with the laundry basket, used as a poster image for Women and Work, reappears as a portrait in Annie Spike’s autobiographical pamphlet A Woman’s Work… (1978), credited to Neil Martinson.

The Hackney Flashers collective has been repeatedly exhibited and discussed. I’m not sure, though, that anyone has looked carefully at the work; that would entail considering the images, texts and their place in the overall array. As much as I would like to provide such an account, I don’t have the scope here to do the kind of close reading that I did for Martha Rosler’s The Bowery in two inadequate descriptive systems. I suspect the Hackney Flashers exhibitions are dense enough to sustain a reading of that type.

The first move of such an account would have to be to refuse the assimilation of the Hackney Flashers’ exhibitions into the discourse and institutions of art. As Liz Heron notes repeatedly the Hackney Flashers have been described as a feminist art collective, but their intention was to produce agitprop, rather than art. This is clear from looking at Women and Work. Separating this project from political documentary or community photography makes little sense. What is more, doing so avoids the challenge involved in recognising that complexly structured photo-narratives don’t just circulate in art space. Engaging with the Hackney Flashers’ exhibitions would necessarily involve questioning high/low culture distinctions and understanding that during the 1970s intellectuals worked in political collectives and popular institutions. Reflexive forms of representation are not confined to the art galleries and museum; if we are ever really to contest hegemony we will have to move out of those elite institutions in search of other audiences. I’m not against art galleries and I won’t call what has happened to these works appropriation or incorporation. The residues of a critical practice need to be maintained in some fashion. The point is to understand that it is a mistake to restrict the practice, and others I’ve been considering, to the category of art.

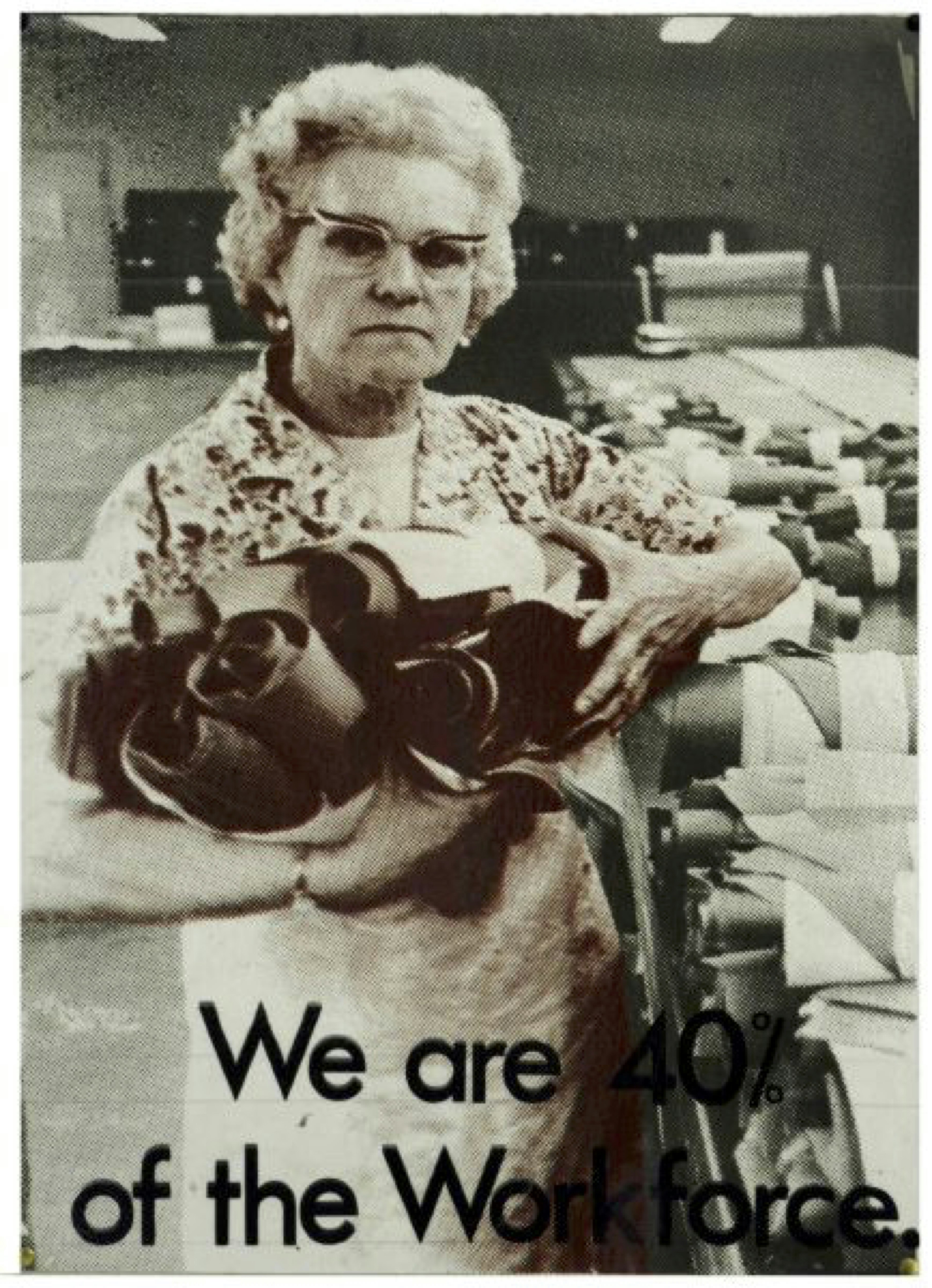

The first exhibition Women and Work (1975) was simply produced using around two hundred and fifty black and white photographs and handwritten text on laminated panels. Panels often contained multiple images with images depicting the range of women’s paid employment in Hackney – factory labour to cleaning. For all the documentary images of working people, it was during the 1970s when we really began to see photographs of people at work and work environments. In Women and Work images of wageworkers were combined with photographs depicting the impact of unemployment, childcare and sexual reproduction on women, along with images of women campaigning for change. The handwritten texts included statistics showing wage-disparities between men and women. As one such text declared, “All workers are exploited, some are more exploited than others”. The work of the Hackney Flashers was important in making visible these systematic inequalities.

Liz Heron noted: “One comment made about the exhibition was taken to heart – there wasn’t enough on the difficulties childcare presents for women. A small exhibition on childcare facilities was subsequently produced for the Under-Fives campaign in the borough. That was instructive for what it didn’t show. The photographs of nurseries and playgroups were useful enough, but the real issue was the long list of children waiting for nursery places, and unlikely to get them. Hackney, for example, had a thousand children on its top priority waiting list for day-care, to say nothing of all the other under-fives who weren’t considered to be in desperate need.”3Heron, “Hackney Flashers Collective: Who’s Still Holding the Camera?”, 124. Finding appropriate representational strategies to depict the invisible processes of capitalism is a central problem of critical documentary. In making this second exhibition the Hackney Flashers opted for a more hybrid mode of presentation, combining photographs and texts with illustrations, montage and cuttings from magazines and newspapers: “We began to juxtapose our naturalistic photographs with media images to point to the contradictions between women’s experience and how it is represented in the media. We wanted to raise the question of class, so much obscured in the representation of women’s experience as universal.”4Three Perspectives On Photography, Hayward Gallery exhibition catalogue (Arts Council of Great Britain, 1979), 80. This expanded vision of documentary isn’t so different in impetus from what Victor Burgin or Mary Kelly were doing, but it was aimed at a different audience of working-class women, trade unionists and socialist activists. Expanded documentary doesn’t have to be confined to the art gallery.

This second exhibition – Who’s Holding the Baby – focused on childcare and was first shown at Centerprise, the radical bookshop, café and community centre in Dalston, which has sadly recently closed. Taking the local focus of a documentary case study the exhibition is a metonym for the economic and social inequalities of class and gender and the way they are entwined. The central object of the exhibition involved highlighting the limited access to childcare in Hackney and the effect of its absence on women’s lives and health. The exhibition shows in photographs, quotations from women and statistics that state provision of nursery care was woefully inadequate. Official childcare had to be supplemented by paying for private childcare, either using private nurseries or childminders. In 1978 there were 471 nursery places and 650 registered childminder places, but 5,600 children under school age whose mothers were working, or who were living in single-parent families. This disparity produces poverty and stress. As one panel demonstrates, during World War II the state provided full-time childcare for working mothers. When women were needed in the workforce the state found the resources, yet in 1987 there were more women in work than at any point since that war. The problem was left for women to solve.

Perhaps, the major part of the exhibition focuses on alternatives to the existing system. This portion opens with one of the few colour images – a magazine advertisement depicting a woman struggling with two young children and advocating as a solution the use of anti-depressant drugs. The Hackney Flashers juxtapose this advertisement with an image of the Hackney Nursery Campaign demonstrating for nursery provision. This panel is titled “Don’t Take Drugs, Take Action”. It is worth recalling that montage is also dependent on the visible politics of documentary. This example juxtaposes an advertisement with an integral image, but even more fragmentary forms of presentation require the ostensive document as the point of reference for the dialectical oppositions. Five panels look at Market Nursery, set up by local women as an attempt at self-organisation: “It’s parents and workers struggling together to get something better for their children.” Undoubtedly this is what Heron had in mind when she described the work of the collective as ‘agitprop’. In these panels we see the collective power of women working together, washing, cooking, cleaning, looking after children and having fun. Work, reproduction and sociability intermix in these panels, as do the people from different ethnic and social backgrounds. Market Nursery occupies a pre-figurative place at the heart of the display. Who’s Holding the Baby not only looks at the situation in which working mothers find themselves, their isolation and enforced poverty, but it also offers self-organisation as the solution. The exhibition is a work of education and organising.

The tension between feminist intellectuals and working-class women surface in these works as problems to be worked through and resolved in practice, rather than by high theory. This is thematised in the film Nightcleaners, where we see a group of feminist intellectuals discussing their distance from the working-class cleaners they were helping to organise. From a socialist-feminist perspective the double oppression of women (as wage workers and as women) must be explained as a feature of capitalism, rejecting dual-system explanations. There were various attempts to produce an integrated explanation of this time, but ‘social reproduction feminism’ has probably been most successful in this regard. The social reproduction debate of the 1970s and early 1980s is currently generating a lot of interest and many young socialists and feminists are excited by the prospects it reopens. In the last couple of years special issues of three influential journals have appeared addressing social reproduction: Historical Materialism, Third Text and Viewpoint. As the philosopher and activist Nina Power has recently written: “What the discussion of social reproduction does is open up the possibility, once again, of a true meeting of Marxism and feminism to begin again to answer the complex questions of sex and value, and the relationship between structure and history, in the twenty-first century.” Social reproduction theory allows for the extension of Marx’s analytical categories in a way that enables us to account for forms of non-class oppression, and therefore opens the possibility of a united opposition to the rule of capital.

From this point of view, women’s oppression is best seen as arising from the organisation of the working-class family and domestic labour. Work of this type includes studies by Silvia Federici, Wally Seccombe, Selma James, Joanna Brenner, Irene Bruegel and more recently, Rosemary Hennessy, Susan Ferguson, Martha E. Gimenez and Tithi Bhattacharya. The central text is probably Lise Vogel’s book Marxism and the Oppression of Women: Toward a Unitary Theory (1983). The capitalist mode of production privatised the social reproduction of the labour force, leaving essential social roles to unpaid women’s labour, including child care, domestic labour – cooking, washing, cleaning, but also emotional support for the male workforce (‘psychic compensation’) – as well as care for the sick and elderly. Central here was the demise of the household production system and the separation of domestic and workspace. It is undoubtedly to the advantage of capital – if not women – for this indispensible labour to go unacknowledged and unrewarded. It is arguable that, to remain profitable, capital will always require this unpaid labour of reproduction. Johanna Brenner and Maria Ramas argue that this situation entails “the capitalist dynamics of production and the exigencies of biological reproduction”.5Johanna Brenner and Maria Ramas, “Rethinking Women’s Oppression”, New Left Review, No. 144 (1984); republished in Brenner’s, Women and the Politics of Class (Monthly Review Press, 2000), 26. Under these circumstances, biological differences between men and women were transformed into systematic inequalities. Under capitalism, these biological differences limit women’s access to the labour market, generalising part-time and low paid work. This situation restricts women’s independence and generates the authority of male members of the household. The state plays its part in stigmatising alternative forms of reproduction and other family forms. In the 1970s the Wages for Housework campaign focused on this disparity.

There is a great deal that would need to be expanded here and I don’t claim that Vogel’s account provides a fully worked out analysis. Her argument is tightly focused on developing analytical categories and whole areas go unaddressed. Vogel has nothing to say about sexual violence, the production of femininity and masculinity, desire.... Much would need to be done to work out how this analysis would feed into the intersectionality debate. Representation and subjectivisation need to be put into this picture to avoid yet another economism. However, what she does provide is a unitary account from which to begin building an analysis of women’s oppression under capitalism. That work urgently needs our attention.

The politics of social reproduction emerged in documentary and photography workshop activities, just as much as in the publications of the women’s movement. This is one reason why the work of Spence, The Hackney Flashers and others are currently drawing so much attention from a new generation of feminist activists. As the text in one panel puts it: “Lack of childcare facilities gives women no choice but to be economically dependent on men, or leave their children with childminders while they are out at work. This is not in the best interests of the children, the women, or the men.” Practitioners from working-class backgrounds (Spence and Hunt are exemplary figures) plaid a prominent role in this activity; but it was just as significant that middle-class women undertook their own voyage to the land of the people.6For a fascinating account of this intersubjective dynamic see Jacques Rancière, Short Voyages to the Land of the People (Stanford University Press, 2003). These women immersed themselves in campaign groups that involved a two-way pedagogy, the teachers received instruction. In centrally representing the experience and struggles of working-class women, socialist-feminist media activists redefined how class is understood. Class re-composition took place in the documentary image, as women’s labour came to the forefront of how we represent and understand work, class and capitalism. Documentary photography was, and will again be, a key resource for this politics of visibility. Today, any Marxism worth a candle will also be feminist or it will not be.