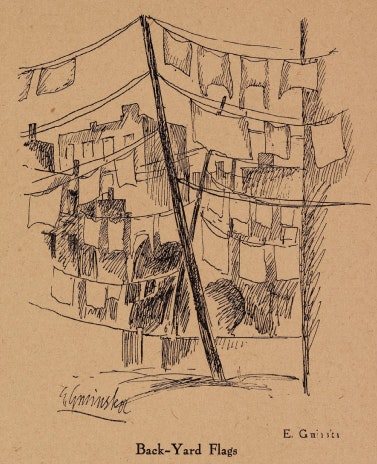

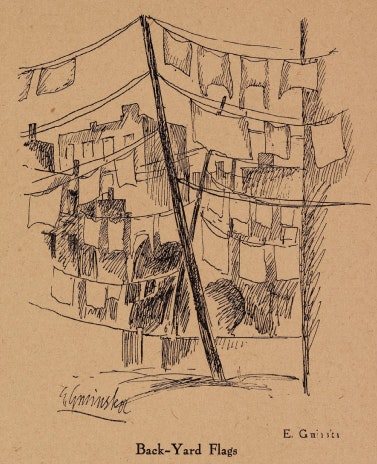

But, again, I want to press the obvious reading by considering why this particular subject became the locus of pictorial investigation, not only for Strand and Stieglitz, but in fact for many photographers during the 1910s (Steichen, Schamberg, Struss, Man Ray, and many Clarence White School students). Already identified by Ashcan School painters such as John French Sloan as private, feminized spaces of sociability where one could catch glimpses of women literally airing their linen in public (seen here in Sloan’s A Woman’s Work, 1912, Cleveland Art Museum), the areas behind buildings were highly contested.